Derek Robinson

A SPLENDID LITTLE WAR

A Splendid Little War is based on fact. In 1919 Britain sent forces from all three Armed Services to Russia, in support of the White armies in their civil war against the Bolshevik armies. Britain also sent military supplies to the value of more than a hundred million pounds — a billion pounds in modern money — to help the White cause. This policy was known as “the Intervention”. It ended in failure. Many British personnel died in Russia or in Russian waters.

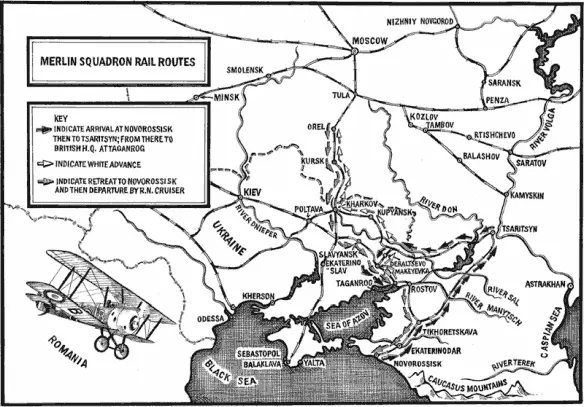

The Intervention was a complex affair. In the Baltic, the Royal Navy engaged in sea battles against the Soviet fleet and bombarded positions inland. In the far south, British units fought Bolshevik forces on the shores of the Caspian Sea, as they did in the far north, at Murmansk and Archangel. British troops were sent to Vladivostok, on the Pacific coast. Training units went to the heart of Siberia, to assist Admiral Kolchak’s anti-Bolshevik campaign, and took part in the fighting. At various times, Canadian, American, French, Greek, Japanese and Czech forces were all involved in the conflict. But Britain was by far the biggest actor, and the biggest spender.

The crucial action centred on the White armies in south Russia, where they were hard pressed by the Red armies. In 1919 a couple of R.A.F. squadrons, manned by volunteer aircrews, arrived to help; this provided the theme for the novel. The story it tells is, I believe, true to the history of the Intervention. For greater detail about what is fact and what is fiction, see my Author’s Note at the end of the book.

D.R.

IN RUSSIA

Wing Commander Griffin, C.O. of Merlin Squadron

“A” FLIGHT (Sopwith Camels)

James Hackett

Tiger Wragge

Jeremy Bellamy

Rex Dextry

Junk Jessop

Daddy Maynard

“B” FLIGHT (DH9 bombers)

Tusker Oliphant

Gerry Pedlow

Joe Duncan

Mickey Blythe

Douglas Gunning

Michael Lowe

Tommy Hopton

Russian Liaison: Count Pierre Borodin

Adjutant: Captain Brazier

Radio and Supplies: Lacey

Lacey’s agent: Henry

Medical: Dr Susan Perry, Sergeant Stevens

Chief Air Mechanic: Flight Sergeant Patterson

Commandant at Beketofka aerodrome: Colonel Davenport

Visiting Officer: Colonel Guy Kenny

Contacts at British Military Mission H.Q.: Captain Butcher, Captain Stokes

Daddy Maynard’s rescuer: Major Edwardes

IN LONDON

David Lloyd George, Prime Minister

Jonathan Fitzroy, aide to P.M.

Advisory Committee: Charles Delahaye (Treasury)

Sir Franklyn Fletcher (Foreign Office)

General Stattaford (War Office)

James Weatherby (Home Office)

COMPLETE CHANGE OF SCENERY

1

Bennett had lost the aerodrome.

Embarrassing. Damned embarrassing.

It couldn’t be more than a mile or two away, but the Camel was shaking like a wet dog. Whatever was wrong with the engine resulted in this huge vibration. His compass was a blur. Smoke swirled into the cockpit and made him choke and cough. Something in the engine had probably broken, maybe a piston rod or a cylinder head, Bennett wasn’t terribly au fait with the workings of a rotary engine. It stuttered and threatened to quit. It was throwing oil: his goggles were spattered with the muck. If he ducked his head to avoid the oil he couldn’t see where the Camel was going, and he knew he had to find a field, any field would do. But when he raised his head and searched, the oil spatter got worse and he couldn’t see through the smoke. He could switch off the engine and stop the spray of oil but he knew the Camel would glide like a brick and he hadn’t much height anyway. What he didn’t know was this Camel was old and tired. The squadron always gave a new boy the worst aeroplane. He glimpsed the top of a pine tree racing past. Crash meant fire, he knew that, knew he must be able to get out fast. He looked down to unfasten his seat belt and didn’t see the next pine. It clipped his left wing. The Camel spun. Bennett got flung into a black and spiky forest at a speed that left his wits far behind him, which spared him the knowledge of what he hit and what it did to him. The Camel flew on, sideways, and met a tall oak tree. Birds panicked for half a mile around. Then silence again.

*

Butler’s Farm aerodrome was three miles from Epping Forest. The airfield had been hastily built in 1917, when Germany began sending formations of Gotha bombers to raid England, and fighter squadrons were hurried back from France to reassure the frightened civilians. The Gothas couldn’t guarantee to hit any target smaller than a town, and sometimes not even that; and the number they killed would have been less than a hiccup on the daily death toll in the Trenches. But the idea of total war was new and shocking to civilians, and so a squadron of the latest Camels came to Butler’s Farm in Essex. The pilots liked it: London was just down the road. A few enemy machines got shot down in flames while Londoners applauded. The threat receded. The Camels returned to France for what, to everyone’s surprise, turned out to be the last year of the war. Not everyone lived to be surprised: air combat killed several, and a few Camels went out of control and buried themselves and their pilots deep in the mud of the Western Front. It could be a lethal little fighter.

After the Armistice, the surviving pilots flew back to Butler’s Farm and the squadron set about rebuilding. Jeremy Bennett was one of the new boys. Eighteen, tall, captain of rugby and cricket at Lancing, he passed out top at Flying Training. The war was over, but his type was exactly what the new Royal Air Force was looking for.

Now the adjutant couldn’t find him.

He’d taken off two hours ago, so he was probably out of fuel, and phone calls to all the local aerodromes drew a blank. The adjutant had asked a couple of pilots to go up, fly around, make a search. Nothing. It was early March, cold and grey. The day was wearing on. A mist was forming.

Then the adjutant’s phone rang. The police had heard from a farmer who’d seen a plane go overhead, sounding wrong, making smoke. Heading? Sort of north, he’d said. When? Hour ago, maybe hour and a half. Why had he waited so long? Harrowing his field. Finished harrowing, went home, reported it. The adjutant pencilled a cross on a map.

It wasn’t much of a search party — two officers and a sergeant mechanic — but then it wasn’t much of a clue. They took the adjutant’s car, got lost in the lanes but eventually found the farm, and the farmer. “Seemed wrong,” he told them. What sort of wrong? “Well, you know. Sounded bad.” He coughed harshly, to demonstrate. “Worse than that. And I saw smoke, too.” Asked how high it was, he pointed to a flock of crows heading homewards. “Twice as high as them.” They got in the car and drove on.

They were both pilots: Wragge, an Englishman, and Hackett, an Australian. At twenty-two, they were hardened veterans of the air war. They had gone to France in the autumn of 1917 and were lucky enough to have joined a flight whose leader could count up to one. He held up his index finger. “Look after Number One,” he told them. “For Christ’s sake, don’t make the Supreme Sacrifice. That’s not going to win this bloody stupid war. The clown who said it’s noble and honourable to die for your country never knew what it’s like to get a bellyful of incendiary bullets at ten thousand feet. Are you listening? Make the other silly bugger die for his country. Then whizz home, fast. Got it?” They got it. They learned more skills from others, and helped a number of German pilots make the Supreme Sacrifice. They were flight leaders when the war ended, with a reputation for quick and efficient killing. Instead of saying damn and blast , the squadron said wragge and hackett!

Читать дальше