Air Ministry terminated Lacey’s commission as an acting pilot officer, so he left the Services. He enjoyed the period of freedom, then became bored and invested his savings in a series of high-risk ventures — night clubs, films, new plays. All failed. In 1923 he re-joined the Army and served in the Pay Corps. In 1925 he vanished, together with a large amount of the Army’s money. He was never arrested. In 1933, ex-Sergeant Stevens met him on a train in France. “He asked me if I thought there would be another war,” Stevens recalled. “I told him it looked likely. He sounded rather nostalgic.”

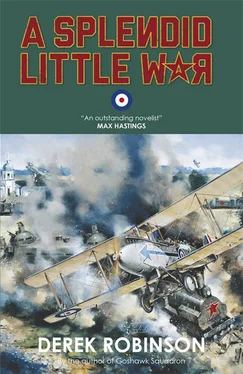

A Splendid Little War is fiction based on fact. The reader is entitled to know which is which.

In brief: the characters are invented but the broad sweep of events is true.

In 1919, Britain did indeed send military forces from all three Services to support the White armies of General Denikin and Admiral Kolchak against the Bolshevik armies led by Lenin and Trotsky. General Wrangel commanded the White Army in the battle for Tsaritsyn (soon to be renamed Stalingrad, and to be fought over in another war) but in this narrative his remarks are invented.

In 1919, Lloyd George was the British Prime Minister and Winston Churchill was his Minister of War. Churchill was obsessed with destroying Bolshevism; Lloyd George was willing to back Denikin and Kolchak while claiming, piously, not to interfere in Russia’s right to decide its own government, a piece of double-think that fooled nobody.

Jonathan Fitzroy’s Advisory Committee on the Intervention in Russia is invented, as are its members: Charles Delahaye, General Stattaford, James Weatherby and Sir Franklyn Fletcher. However, the events that they discuss are true. For example, when Weatherby speaks of mutinies by British Army units in Luton, London and Calais, he is referring to actual events. Similarly, discussion of the Irish problem, or the Royal Navy’s successes at Kronstadt, or the campaign to hang the Kaiser, and many more, are all based on fact.

The Royal Air Force raised new squadrons as part of the Intervention. These flew Camels, DH9s and other aircraft, left over from World War One and showing their age. My accounts of their performance in combat are as accurate as I could make them. An R.A.F. squadron fought in the battle for Tsaritsyn, and it made the long journey — first westward, to Taganrog, and then north for some eight hundred kilometres, to Orel — in support of Denikin’s fast-moving assault, before retreating an even greater distance, to Novorossisk and evacuation by the Royal Navy. However, Merlin Squadron is my invention and none of its officers and men is based on actual R.A.F. personnel. The same applies to Count Borodin and to other Russian officers.

Some incidents in the narrative may seem bizarre or improbable. Was there a Russian religious cult, known as the Skoptsi, whose members self-mutilated in accordance with the teaching in Matthew, chapter 19? There was indeed. And it is true that the British Military Mission H.Q. in Russia issued each aircrew officer with a phial of morphine, both for medical treatment and as a last resort if captured; similarly; ‘Goolie Chits’ were attached to aircraft in India. Both Red and White armies routinely shot any enemy officers they captured, just as units that mutinied or deserted usually shot their own officers. Details of the elaborate banquet to mark the fall of Tsaritsyn are typical of Russian celebrations in those days.

The part played by the London Scottish Regiment in the Somme offensive is based on fact but Colonel Kenny V.C. is fiction. On the other hand, Lieutenant Agar V.C. did indeed lead the M.T.B.s that destroyed the Soviet fleet in Kronstadt; similarly, Lieutenant Colonel Johnson did command a battalion of the Hampshire Regiment in Siberia, where he came to regard the situation as “pretty hopeless”, and led a dozen soldiers in the extraordinary journey to Archangel, which I have described.

My accounts of Nicholas II — first as a happy youth, then a reluctant Tsar, lastly as a disastrous Commander-in-Chief — follow the facts, as does Rasputin’s success with ladies of the nobility. Nestor Makhno’s Anarchist Brigade was a brutal reality in 1919, and the sad inadequacies of Russian hospital trains were all too true: disease, especially typhus, was rife. The vast wine cellars, used by Denikin to fund his treasury, existed, although not exactly where I located them. Another detail: the idea of decorating a ceiling with black footprints was not invented by aircrew in World War Two; it began a generation earlier.

The Royal Navy kept a large fleet in the Baltic, enjoyed victories and suffered casualties, mainly from mines; and Lloyd George did indeed — briefly and secretly — declare war on Soviet Russia. At the other extreme, Susan Perry’s pragmatic embalming technique reflects the methods of the time. The scale of official corruption at all levels, and especially the theft of British aid to Denikin, was as great as I indicate, and possibly greater; it was a large reason for his ultimate failure.

I have tried to do justice to the qualities of the Russian armies, both White and Red. The truth was enormously complicated. This book is primarily about the experiences of an R.A.F. squadron, living in trains and often isolated from the population, and so the picture of the wider campaigns must be sketchy, and — for purposes of narrative convenience — somewhat telescoped.

What they discovered about the Russian military — that it could be both brave and incompetent, resolute and corrupt, loyal and treacherous, long-suffering and thoughtless — left the R.A.F. officers baffled and bewildered. Atrocities were committed by both sides. Nichevo and vranyo played a real part in Russian life, and for all I know they still do. In the end, my reported comment of the bomber pilot who wished that both sides would lose reflected the views of many who served in the Intervention.

Life on an R.A.F. squadron in the Intervention was a strange mixture of bloody combat and a summer holiday in the countryside. They travelled by train, in some comfort, with plennys acting as batmen. Often the surroundings were pleasant, and an officer might take his horse and go shooting or fishing. They were nominally part of a White army, but in fact they were largely independent and a long way from British Mission H.Q. In those circumstances, it is not altogether surprising that a squadron might realize that Moscow was within range and plan to bomb it. This plan did, in fact, take shape. It seemed an obvious and desirable step to take in a war. Moscow had been the goal all along. It was the enemy’s H.Q. If it could be hit, why not hit it? When Mission H.Q., and then London, firmly refused permission, this must have seemed to the squadron a foolish decision. In London’s eyes, it was a wise precaution. The Russian Civil War was not yet won and lost. There was no merit in impetuous gestures.

There can be no doubt that the Intervention left Russia feeling threatened on all sides. After World War Two — when 1919 was only a generation ago — the Iron Curtain had one great merit from the Soviet point of view: it defended Russia’s borders against attack. In 1957 Nikita Khrushchev, on a visit to the United States, declared: “All the capitalist countries of Europe and America marched on our country to strangle the new revolution… Never have any of our soldiers been on American soil, but your soldiers were on Russian soil. Those are the facts.” The Intervention of 1919 cast a long shadow.

None of this can be confirmed or refuted by reading an Official History of the Intervention, because that work was never written (or, if written, was never published). No doubt Lloyd George’s government saw nothing but embarrassment in detailing the decision-making behind a venture that was costly in blood and money at a time when Britain could afford neither, and which ended in total failure. Compared with other campaigns, few first-hand accounts of the Intervention survive. The Day We Almost Bombed Moscow , by Christopher Dobson and John Miller (Hodder & Stoughton, 1986) tells the story of that incident and of many other facets of the Intervention. Two sets of memoirs by serving officers are very revealing. Farewell to the Don (Collins, 1970) is the journal of Brigadier H.N.H. Williamson, an artilleryman whose task was to advise and instruct Denikin’s armies. He travelled widely and saw both the best and the worst of the Russian soldier. Last Train Over Rostov Bridge (Cassell, 1962) is by Captain Marion Aten D.F.C., whose squadron flew Camels in many combats against the Red air force. They arrived in Russia full of enthusiasm and left it, months later, a lot wiser and not sorry to get out. The immediacy of their experience makes their accounts invaluable reading. Of other books on the subject, The Victors’ Dilemma: Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War , by John Silverlight (Barrie & Jenkins, 1970) is scholarly and invaluable.

Читать дальше