None of us answered, but he waved his hands at us. “Get dressed now,” he said. “Your clothes are dry. My wife and children will be here very soon, and they can’t see you like this.”

We stayed the rest of the day, and he let us sleep another night in the stable. Jehoash said we’d have to head off the next day.

“Yes,” said the man, “that’s fine. I’ll take you to the nearest road, so you can make your way back.”

His wife made us some more food, the children ran about, laughing and shouting, even smiling at Jehoram. Reuben went to help with the animals, while Jehoash sat there with Jehoram, playing with the youngsters. The eldest child, Martha, asked me how we’d made it past all the dangers, what powers had driven us to their land. The locks of her hair hung down, there was a warm reddish color in her cheeks, and her skin was paler than I’d seen in our people.

Her mother told me not to mind Martha and what she said. “She likes stories so much, she doesn’t think of anything else,” she said. Martha blushed and lowered her eyes. I leaned toward her and asked what kind of stories she liked. Martha shrugged, still staring at the ground.

“Well, listen to this, let me tell you,” I said, “about the powers that called us and chased us here. It was a night as black as the deepest abyss, and we walked and walked. We fought wild animals, they chased us through the valleys, howling, snarling, and growling. When day finally broke and we thought it was all over, the storm came. It was as if the sea itself came washing over us. The water was threatening to tear us apart. But you see that man over there, the one with those eyes? That’s Jehoash. Jehoash took hold of us, found a rope, and tied us together. We were lifted up by the water, thrown down, but we were tied to each other and were washed all the way here.”

Martha’s hands hung down by her sides, and her lips moved.

“Well,” I said, “did you like the story?” She didn’t answer, just stood there, talking silently to herself.

“Martha,” said her mother, “you must answer when Nadab asks you something.”

“I’m learning the story,” said Martha. “I collect them, please, I have to tell it back to myself.”

I let her carry on. She was a strange child. It seemed as if her eyes were always searching for something. Her fingers were long and thin like slender twigs. She spoke to me not like a little girl, not like a grown woman. Everything she said seemed to be extracted from a hidden place.

“I’ve learned it now,” she said. “I’ve got your story now. Please can I look after it until you need it again?”

“Yes,” I said, smiling. “Of course, it’s yours.”

“No.” She shook her head. “I won’t take your story from you.” Her mother interrupted and told her she shouldn’t argue with guests or try to confuse them with words.

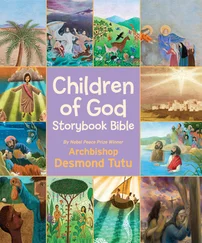

“Mother’s stories are the best,” said Martha. “She tells them almost every evening. Can you tell us about Jesus, Mother? Tell us about when you and Father met Jesus.”

“Not now,” said her mother. “Our guests need to rest. Didn’t you hear what he told you?”

“Have you seen Jesus?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Martha, her voice singing. “Father and Mother have spoken with him. They joined his followers.”

“Why don’t you lend me a hand, Martha?” said her mother. “Leave our guests in peace.”

“But Mother,” said Martha. She didn’t get any further, as her mother took hold of her and dragged her away, telling her softly about being quiet and doing what she was told.

I got up and asked if there was anything I could do. Jehoash spoke up and said I could go and fetch some water. The woman looked at Jehoash, then at me, and said it wasn’t necessary. But Jehoash said it was only fair and proper, they shouldn’t be our servants.

“If you want to,” the mother said. “If you wish, you can go down to the stream.” I nodded. The woman gave me a pitcher and told me where to go. Jehoash followed me out.

“Have a look around,” he told me. “That’s all. Just have a look around, and then come back here.”

A path led me through a small thicket and down to a stream. The water flowed silently through the rushes, flies and other insects buzzing over the surface. I was still dazed from the night before and sat down on a flat, dry stone.

Martha must have followed me. She came down the path from behind me.

“Why are your hair and beard that color?” she asked. I told her she shouldn’t be there, but she just snorted and said she was big enough to make her own decisions about where she could and couldn’t go.

“Mother thinks I went to clear the small patch of ground where we’re going to plant trees,” she said. “Do you know how long it takes for a tree to grow?”

I shook my head.

“A long time,” she said. “It won’t make any difference if I go to pick up stones today or tomorrow.”

She went on to tell me about how she always helped her father on the land, how her days were split up, and how black the nights could be. “Sometimes I can’t see anything,” she said. “It’s as if I couldn’t tell the difference between what’s up and what’s down.”

I told her about the time when I’d been out by the coast and had seen the night reflected in the sea. She asked what the sea was like, what it smelled like, whether it made a noise, whether the water was heavier or lighter than in the stream there. I told her I didn’t know, but that it seemed heavier in a way, and that it was never still.

“You can always hear it,” I said. “You can hear it whispering against the shore. If you put your head beneath the water, you can hear something pounding and groaning down in the depths.”

“It can’t be the same water,” said Martha, lying down on her stomach with her ear to the stream. A gentle breeze blew over the fields and down to us. We saw it sketch a pattern across the water.

I asked if her mother had really met this Jesus.

“Oh yes,” said Martha. “He comes from Nazareth. It’s a small, poor town, Father says, up in the hills. He has long hair and a beard, and Mother says he touched her and Father.”

Her mother and father had met Jesus when they’d gone to the nearest market. They’d seen him defend a farmer who couldn’t afford to pay his taxes. “Give your master what belongs to your master, and give God what belongs to God,” Jesus had told the guards. He put his arm around the farmer and said, “We are children of God, we need our daily bread.”

After that, her mother and father had sought out Jesus and his followers. He’d laid his hands on them, and they’d been baptized with the Holy Spirit and fire.

“The Lord himself,” I said, and tried to smile at her, but Martha wasn’t paying attention to what I said. She went on with other stories about Jesus, stories that her mother and father hadn’t witnessed, but that they’d been told. The sick had been cured, the unclean had been cleansed. A woman who sold herself had been cleansed by Jesus and walked by his side. Rebels had come down from the mountains and lay down their arms. Violent men had received the Word of God, and fire had flowed from their fingers. Children who had been abandoned, marked by the Devil, ran around Jesus’s feet, with God in their eyes.

Martha was no longer speaking like a little girl. Her voice seemed to have its own life, like a snake slithering and writhing, sliding and winding. The stories Martha told were broken off at the ends and began suddenly. Sometimes she would mention a name, other times a city. At first, I thought she was trying to get everything to fit together, to suggest the clear pattern according to which the world was arranged. But it wasn’t like that, no, it was different. She let her stories twist and coil, as if they were being put around me like a fortress against all evil.

Читать дальше