She found an extra bedroll for me, and while the insurgents prepared for an uprising all around me, Auntie Iryna nursed me back to health one teaspoon of soup at a time. She told me that I was a survivor, as she was. And that the way to honour our family and friends was to be strong and to live and to tell their stories.

“Who will remember them if you give up?” she asked.

Auntie Iryna found the photos and the ripped-up drawings in my pocket. She made a glue of flour and water and carefully pieced the portraits back together. We hung them on the wall of our cave. I found comfort in looking at Dolik and his family. But sometimes I’d wake up weeping, wondering if the Kitais were staring down at me in judgment because I couldn’t save them. On those nights it was hard to get back to sleep.

Auntie Iryna liked to look at the wedding picture of Mama and Tato — the one that Mr. Segal had taken so many years ago — before the sadness, before the war. “Look in their eyes,” she said. “See the hope and joy for the future. They want that for you.”

When I was stronger, she showed me the photograph of Mama and me and Maria, the one that had been taken by Mrs. Segal. I held it to my heart and wept.

“You know that Maria is alive and safe,” she gently reminded me, her arm wrapped around my shoulder. “She’s probably on that farm in Austria by now, with Nathan. I think you need to find her. That’s what your mother would want.”

“Did you know that Auntie Stefa had wanted Mama and Maria and me to go to Canada and live with her?”

“Your mother told me,” Auntie Iryna replied. “She confided in me once that her biggest regret was not taking Stefa up on the offer before the war.”

“She couldn’t possibly have known how bad things would get here,” I said.

“That’s true,” said Iryna. “But I think your mother would rest easy in her grave if she knew that you and Maria were with Stefa.”

“I need to find Maria,” I said. “And if we survive this war, we will go to Mama’s sister.” The thought filled me with hope. “Can you teach me what you know, so I’ll have the strength and skill to find my sister?”

“You already have the strength, Krystia. You’ve proven that. But the skill — that I can help you learn,” said Auntie Iryna, hugging me fiercely.

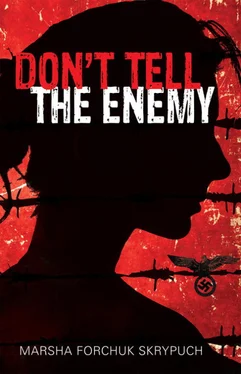

Don’t Tell the Enemy was inspired by the true story of Kateryna Sikorska and her daughter Krystia, who hid three Jewish friends under their kitchen floor during the Holocaust.

Krystia is now a senior citizen who lives in Canada. Her daughter, journalist and filmmaker Iryna Korpan, approached me in 2012 at a public event. She handed me a copy of her excellent documentary called She Paid the Ultimate Price and explained that it was about her own mother’s and grandmother’s heroic actions in World War II Ukraine. She asked if I would consider writing a book about it.

After reviewing the documentary and doing some preliminary research, I agreed. I had originally planned to write this book as non-fiction, but as I got into the interviews and research, I realized that writing it that way would not do the story justice. Many of the people who lived through those times had perished. How could I interview them? How could I quote them?

But the other problem was that as I delved into the complicated events of the time, I realized that the story extended far beyond Krystia and her family.

I archived my original manuscript and started from scratch. I located memoirs and narratives of other people in the surrounding towns to create fictional characters based on composites of those real people.

However, my heroine is true to the real Krystia. Her younger sister was Maria, and her father was a blacksmith who died before the war. Her Aunt Stefa sent packages of goods, like stockings, from North America for the family to sell should the need arise.

Dolik and Leon were Krystia’s next-door neighbours. Their mother was a doctor and their father ran a stationery store from the house. Photographer Michael Klar and his wife, Lida, lived across the road from Krystia. Michael Klar took the wedding photo of Krystia’s parents. He and his wife are my inspiration for Mr. and Mrs. Segal.

While pasturing his cow a few kilometres outside their town, Krystia’s uncle was shot and killed by a Soviet soldier. Her cousin was killed by the NKVD — his body so brutalized that the only way he could be identified was by his crooked baby finger.

Ukrainian insurgents did capture the radio station in Lviv and declare independence from the Soviets and the Nazis. They posted flyers to this effect all over the area. These posters were quickly taken down by the Nazis, and those leaders of the independence movement who were captured were sent to concentration camps.

Krystia really did sneak food into the ghetto and spirit out photographs. Her mother and uncle worked with Ukrainian insurgents in the area to create false documents that helped save Jews. Krystia’s mother also sneaked onto the train to sell goods in Lviv.

The first names of the three Jewish friends that Krystia’s family hid were indeed Dolik, Leon and Michael. The real Nathan escaped using the false document that had been provided by Krystia’s family.

All of the atrocities are based on documented Aktions in the area, orchestrated by the Nazi regime to carry out the Hunger Plan and the Holocaust.

The Commandant and his actions are inspired by a Kriminalpolizei officer named Willi Hermann who was personally involved in the liquidation of the Jews in the area.

Krystia’s mother’s fate is real, as is that of Dolik, Leon and Michael.

But Don’t Tell the Enemy is a novel, not non-fiction. My story is framed around these people and events.

The real-life Krystia was only eight years old in 1941, though her courageous actions were that of a mature individual. Today’s readers might have difficulty understanding that someone so young could accomplish all that Krystia did. I felt that making her older would make her actions more relatable.

Maria was only seven. Dolik and Leon were older teens. For the sake of the story I made them closer in age to Krystia so they could be classmates and friends.

Krystia also had an older sister named Iryna, who was ten, but it was Krystia who took Krasa to their pasture twice a day and sneaked food and documents into the ghetto to help the Jews.

Krystia’s actual town was Pidhaytsi, which means “under the wood.” I’ve named it Viteretz, which means “breezy,” and I’ve made the town much smaller. I populated my novel with composite secondary characters based on my research.

Righteous Among the Nations

Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Israel, conveys gratitude to non-Jews who took great risks to save Jews during the Holocaust by naming them Righteous Among the Nations. Those honoured with this title are listed in a database and have their names engraved in a memorial at Yad Vashem.

Those caught hiding Jews in Pidhaytsi, and in other areas of Occupied Poland that are now part of Ukraine, were treated much more harshly by the Nazis than rescuers in other parts of Europe. Ukrainians risked death not only for themselves, but for their entire families. In spite of those high stakes, more than twenty-five hundred Ukrainians have been recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem for their efforts in rescuing Jews during the Holocaust.

Kateryna Sikorska’s family is among them.

A note about terms used in this book:

German and Nazi are not interchangeable: German and Volksdeutche refer to ethnicity, not political beliefs. Some Germans and Volksdeutche who opposed the Nazis became victims too. Others were executed or sent to slave labour camps by the Soviets.

Читать дальше

![Quiet Billie - Don't mistake the enemy [СИ]](/books/421973/quiet-billie-don-t-mistake-the-enemy-si-thumb.webp)