After ten days he said he had to move on, that there were other camps with deportees who were suffering. I gave him all the letters I had written to Andrius. He said he would mail them.

“And your father?” he asked.

“He died in prison, in Krasnoyarsk.”

“How do you know that?” he asked.

“Ivanov told my mother.”

“Ivanov did? Hmm,” said the doctor, shaking his head.

“Do you think he was lying?” I asked quickly.

“Oh, I don’t know, Lina. I’ve been to a lot of prisons and camps, none as remote as this, but there are hundreds of thousands of people. I heard a famous accordion player had been shot, only to meet him a couple of months later in a prison.”

My heart leapt. “That’s what I told my mother. Maybe Ivanov was wrong!”

“Well, I don’t know, Lina. But let’s just say I’ve met a lot of dead people.”

I nodded and smiled, unable to contain the fountain of hope he had just given me.

“Dr. Samodurov, how did you find us?” I asked him.

“Nikolai Kretzsky,” was all he said.

JONAS SLOWLY BEGAN to heal. Janina was speaking again. We buried the man who wound his watch. I clung to the story of the accordion player and visualized my drawings making their way into Papa’s hands.

I drew more and more, thinking that come spring, perhaps I might be able to send off a message somehow.

“You told me those Evenks on the sleds helped the doctor,” said Jonas. “Maybe they would help us, too. It sounds like they have a lot of supplies.”

Yes. Maybe they would help us.

I had a recurring dream. I saw a male figure coming toward me in the camp through the swirling ice and snow. I always woke before I could see his face, but once I thought I heard Papa’s voice.

~

“Now, what sort of sensible girl stands in the middle of the road when it’s snowing?”

“Only one whose father is late,” I teased.

Papa’s face appeared, frosty and red. He carried a small bundle of hay.

“I’m not late,” he said, putting his arm around me. “I’m right on time.”

~

I left the jurta to chop wood. I began my walk through the snow, five kilometers to the tree line. That’s when I saw it. A tiny sliver of gold appeared between shades of gray on the horizon. I stared at the amber band of sunlight, smiling. The sun had returned.

I closed my eyes. I felt Andrius moving close. “I’ll see you,” he said.

“Yes, I will see you,” I whispered. “I will.”

I reached into my pocket and squeezed the stone.

APRIL 25, 1995

KAUNAS, LITHUANIA

“What are you doing? Keep moving or we won’t finish today,” said the man. Construction vehicles roared behind him.

“I found something,” said the digger, staring into the hole. He knelt down for a closer look.

“What is it?”

“I don’t know.” The man lifted a wooden box from the ground. He pried the hinged top open and looked inside. He removed a large glass jar full of papers. He opened the jar and began to read.

Dear Friend,

The writings and drawings you hold in your hands were buried in the year 1954, after returning from Siberia with my brother, where we were imprisoned for twelve years. There are many thousands of us, nearly all dead. Those alive cannot speak. Though we committed no offense, we are viewed as criminals. Even now, speaking of the terrors we have experienced would result in our death. So we put our trust in you, the person who discovers this capsule of memories sometime in the future. We trust you with truth, for contained herein is exactly that—the truth.

My husband, Andrius, says that evil will rule until good men or women choose to act. I believe him. This testimony was written to create an absolute record, to speak in a world where our voices have been extinguished. These writings may shock or horrify you, but that is not my intention. It is my greatest hope that the pages in this jar stir your deepest well of human compassion. I hope they prompt you to do something, to tell someone. Only then can we ensure that this kind of evil is never allowed to repeat itself.

Sincerely, Mrs. Lina Arvydas 9th day of July, 1954—Kaunas

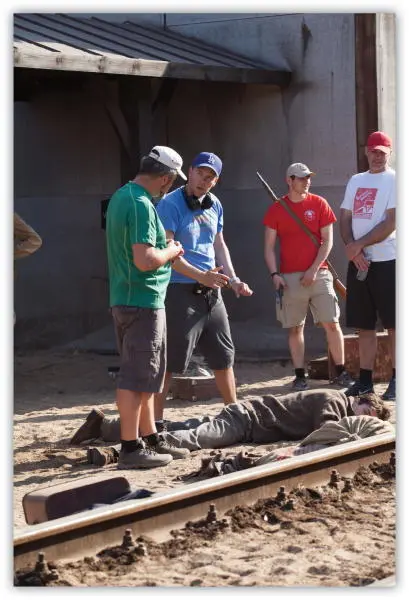

A behind-the-scenes look at the making of the film Ashes in the Snow

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Film slate!

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina comforts a grieving Andrius. Left on the cutting room floor! This scene does not appear in the film.

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina draws and documents the deportation and her experience in Siberia. When the NKVD discover her drawings, they burn them. Lina’s drawings quickly become ashes in the snow, hence the title of the film.

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina is forced to watch as the NKVD burn her drawings. Challenging to shoot because temperatures rose and the production team had to create fake snow!

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina braves winter in the Arctic, fighting not only for her own life but for the lives of her fellow prisoners.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

The entire film was shot on location in Lithuania and the majority of the production crew was Lithuanian. Lithuanian cities featured in the film include Vilnius, Nida, Palanga, and Kaunas (featured in photo).

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Upon seeing her drawing, Andrius assures Lina that she will be accepted to art school.

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina’s mother, Elena, bravely addresses the guards in defense of others.

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina makes her way to Andrius, who is digging a grave. This scene was deleted from the final cut of the film.

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina and deportees at the weigh station after a day of work in the beet fields.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

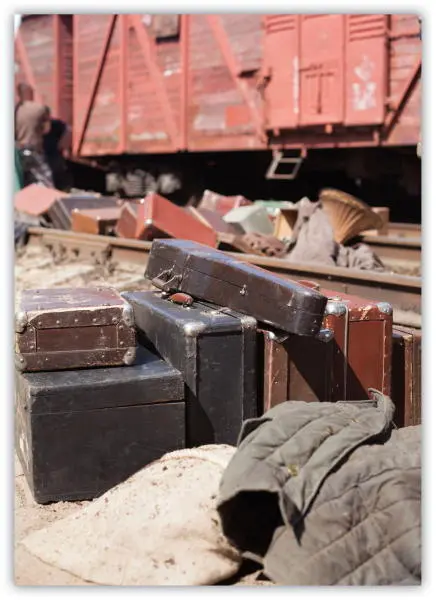

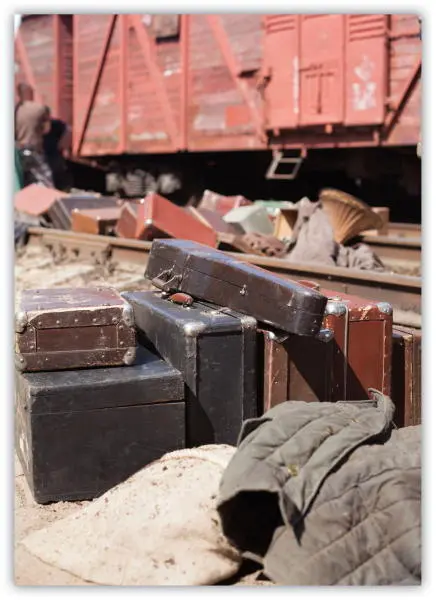

The train tracks leading Lina, her family, and the deportees away from Lithuania. Securing and aging actual trains for the film was one of the biggest challenges for the production team.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

An NKVD officer guards the locked train cars filled with Lithuanian deportees.

Courtesy of Sorrento Productions & Tauras Films

Lina, determined to find food and save her family.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Deportation scene at the train station where many deportees were separated from their luggage.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

The truck that Lina and her family were loaded into during the scene of deportation from their home.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Off-camera, Bel Powley (Lina) watches a scene via the monitor.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

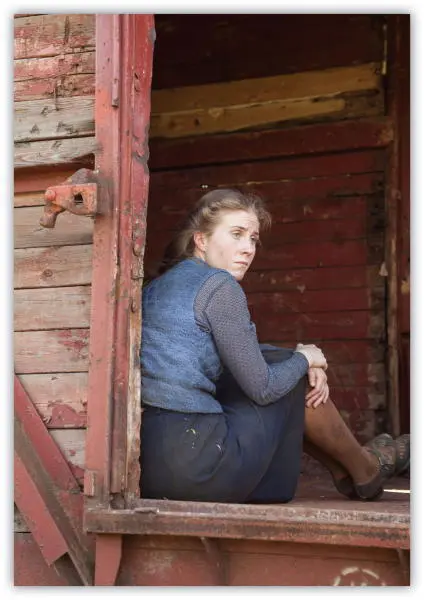

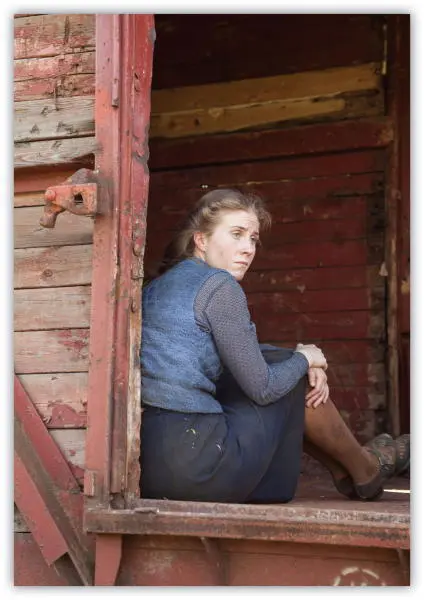

An extra rests in a train car between takes.

Vytautas Juozenas for SEG Inc.

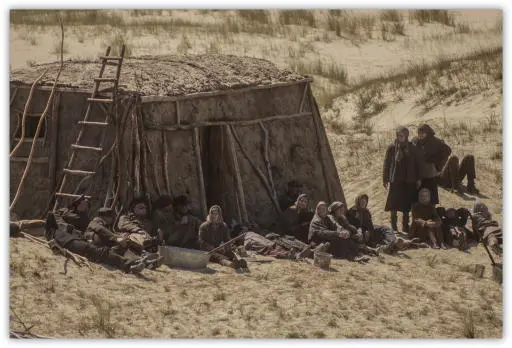

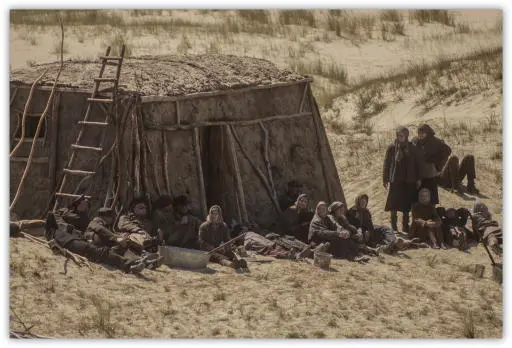

Extras waiting to shoot a scene near the jurta. They were costumed in heavy clothes, though this was shot in late May on an extremely hot day.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Guards in the train depot.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Actors portraying the NKVD prepare to shoot a scene with Commander Komarov and Kretzsky at the train station.

Vytautas Juozenas for SEG Inc.

An NKVD officer shows his mettle and prepares to shoot.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

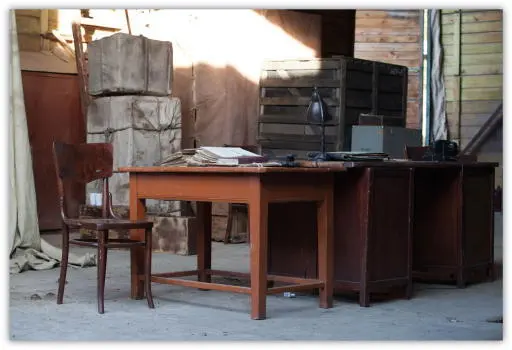

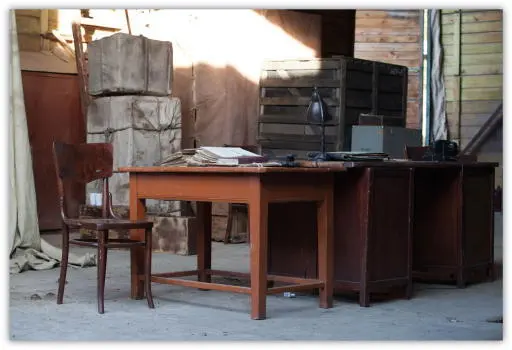

Files outlining prisoners’ charges on the desk in the train depot.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Watching via the monitor as cameras roll during Lina’s flashback scene of her summers in Palanga.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Ruta Sepetys on set with Martin Wallström (left) as Kretzsky and director Marius Markevicius (center).

Vytautas Juozenas for SEG Inc.

Hands of a deportee. The wardrobe and makeup departments tasked specific staff members with applying dirt and aging throughout the production.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

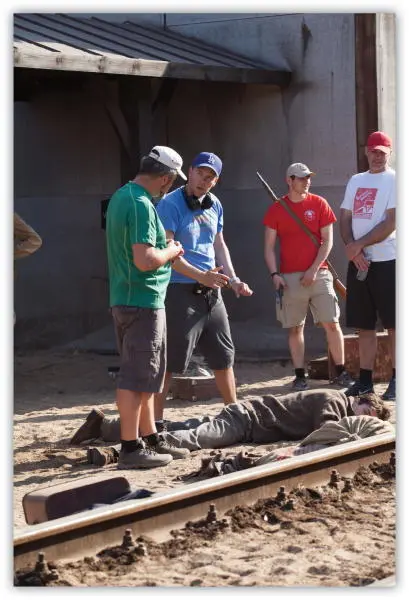

Director Marius Markevicius (second from left) plans a shot of Andrius (center, lying) with cinematographer Ramunas Greicius (left).

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Author cameo! Ruta in costume, hair, and makeup before filming a scene as an extra.

Photo: 2016 J. Michael Smith

Ruta Sepetys (center) on set with the extras in the film, some of whom were survivors of Siberia themselves and many of whom had relatives who were deported.

Читать дальше

![Рута Шепетис Ashes in the Snow [aka Between Shades of Gray] обложка книги](/books/414915/ruta-shepetis-ashes-in-the-snow-aka-between-shades-cover.webp)