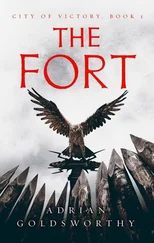

It was time to go, and he made his farewells and was forced to promise to pay another visit, tomorrow or the next day at the latest.

‘Yes, you absolutely must, my modest hero,’ Enica declared. ‘If you do not come then I shall send Achilles to hunt you down. He may be small, but he is implacable – and he can bite in some truly unpleasant places! Oh do not frown like that, dear Claudia, none of the children are in earshot and it was merely a jest. How do you know I was not talking about his knees anyway?’

‘Do not shock our guest,’ Claudia Severa said, trying her best not to smile.

‘I should feel a great sense of achievement if I managed to shock a centurion of the legions. Especially this one.’

Ferox gave a slight bow. As he left he saw Longinus and three other Batavians arrive, one of them Cocceius and all carrying packs and tools. The one-eyed veteran explained that they were planning to build a little fort and pitch a tent inside for the children.

‘Will it be to keep us out or keep them in?’ Ferox joked. He talked to them for a while, but was once again late, so he invited them to join the party going to the baths. The three soldiers were obviously enthusiastic.

‘We’ll see,’ the veteran said. ‘Work to do first.’

Ferox left and started off downhill towards the river. The streets were barely less crowded than earlier, and soon he was surrounded by bustle and noise, as people talked and yelled in half the languages of the empire. Almost at once, he sensed that he was being followed. He carried on, as if he had noticed nothing, hoping the pursuer would draw close. His cloak was tight around him again, and he kept his hand around the handle of the pugio, a handier weapon than the sword in such a crowd. Nothing happened, but once he turned suddenly and was sure he saw the face of the slave who had brought the message the night before. The man blinked, realised he had been seen and vanished into the crowd.

‘Alms for an old soldier.’ A man missing a leg and supporting himself on crutches stood in front of him. ‘Please, sir, for the sake of the aquila .’

Ferox gave the man a couple of coins. So many beggars claimed to be old soldiers and more than half were probably lying, but this man had the air of a former soldier about him.

‘Which legion?’

‘Hispana, sir. Fifteen years until I lost this.’

‘Good luck to you, legionary.’

‘Thank you, sir. Best fortune to you for your kindness.’

There was no sign of the scarred slave, and the press was too thick for there to be much hope of finding him. Ferox went on, soon reaching the streets nearer the quayside, where the scent of fish filled the air.

The others were waiting by the main bridge, as they had promised.

‘Time to introduce you to civilisation and cleanliness,’ he said.

Vindex rubbed his chin. ‘Are you sure this is a good idea?’

OVIDIUS WAS SO excited that his words tumbled out almost as fast as Claudia Enica in full flow. He had worked on in the archives until the third hour of the night, a special order from the legate forcing a few of the staff to stay with him, do as they were bid, and make sure the old fool remembered to drink and have something to eat. The next morning they again waited on Neratius Marcellus, and while they did Ovidius scarcely paused to draw breath as he told his story. Ferox listened with patience, and because the only way to have interrupted would have been to grab the old man and shake him bodily.

Did Ferox know that Agricola was a broad-stripe tribune under Suetonius Paulinus? Yes, of course he did. And that the legate took a shine to the diligent young officer and kept him with him throughout the expedition to Mona and when they turned around to meet Boudicca? Perhaps not. He trusted him with activities that were not generally made public, and one was to deal with this Prasto, who had been captured by chance a year before and decided that his hide was more precious than his cult. Agricola was tasked with keeping a close eye on the man and with learning as much as they could. There had been rumours of captives kept alive by the druids for years, including at least one narrow-stripe tribune, and the governor was keen to discover whether or not there was any truth in this. If there was, their rescue came second only to destroying the cult.

‘And as far as I can see, Prasto took with relish to the task,’ Ovidius went on. ‘It turns out that he was in dispute with many of his fellow druids, something to do with seniority, which he felt had been unfairly denied to him. So he was happy to see his old colleagues put to the sword, and the sacred groves cut down or burned. A man of strong passions, it seems! Yes, yes. More murderous in revenge than his fellow priests were in their grim religion. Led the Romans to Mona, and then guided them so they knew just where to strike and who needed to be caught and killed. Helped a lot in dealing with the rebels too, because he knew Boudicca and most of the chieftains quite well. The gods only know what they thought of him! Still, if he was a traitor, he was our traitor, and very useful too, more than justifying the reward of a plush villa by the sea and enough gold and silver to live in comfort. Agricola remembered him when he came back, and employed him again, and one of the results was this!’ The old man brandished a scroll.

The usher had to raise his voice and repeat his message before the oration ceased and Ovidius realised that they were summoned. Ferox and the slave both had to hurry to keep up as the old man almost danced along the corridors.

‘No luck, I see,’ the legate said as his friend bounced into the office. Crispinus grinned. He was the only other person in the room once the slave closed the doors behind them.

Ovidius went back to the beginning, starting with getting the note from Ferox, and then went through his search, the false starts, growing despair at another trail apparently leading nowhere, and then the thrill when he saw the name. Neratius Marcellus listened with patience and growing interest. ‘And when can we expect the first reading of the poem about this great quest?’ he said when the old man finally stopped and slumped down exhausted. ‘What about you, Ferox, anything to add?’

‘Only a little, my lord. I found a Batavian whose father had served and been one of Prasto’s escorts.’ In fact, Longinus was his source, speaking a little more freely than usual the night before as the wine had flowed. There was something about Gannascus’ huge and merry presence that made other men relax. After several hours in the baths they had gone to some bars, and spent a long time watching the dancers in one tavern, the lithe girls in skimpy leather costumes.

‘I must be getting old,’ Longinus said as he joined Ferox in a quieter corner. After a while he coaxed the story from the veteran. He had served in cohors IV Batavorum, one of the old units disbanded after the rebellion that Longinus-Civilis had led. ‘In those days they used to send us noblemen to serve as a trooper for a year or two before they made us prefect. Good system, since you got knocked about a bit – but not too much because they knew you would come back very senior – and at least knew a bit about soldiering when they made you prefect.’ He remembered the turncoat druid. ‘That bastard. An animal or worse. Never forget him even if I tried. I’ve met some wrong ’uns in my time – well, I knew Nero and Vitellius – but that sod didn’t even try to hide it. Wish I could forget.’ Ferox knew how the veteran felt, for now that he had heard what had happened he half wished he could forget.

‘Prasto was vicious,’ he told the legate, ‘even more than the noble Ovidius has told us. He tortured and killed with such glee that even the legionaries were sickened, and you probably know how much they loathed the druids, especially once the stories came out of what Boudicca’s warriors were doing. Prasto hated and desired many of the women who were part of the cult.’

Читать дальше