They wandered hand in hand to the huge double-height courtyard. The centre space was deep in volcanic debris, which had even buried a mass of upended amphorae that had been waiting to be filled. The intended grape or olive harvest must be lost in the fields, choked or burned.

Tentatively feeling for stair treads, they climbed to the upper storey where they cleared the deep ash by shoving it off the balcony. Marciana was by now so tired and drained, she dropped asleep immediately against a remaining drift of debris. After making sure she would not sink in and suffocate, Larius went for a short mooch, wading along the dark upper verandah. Fathers have to check the house. Fathers prowl the perimeter, on guard. When a long day ends, fathers wander off by themselves, looking up at the stars while perhaps they fart quietly to show that they don’t give a damn, while they think about their responsibilities.

There were no stars. But if you could ignore the constant volcanic commotion, there was time to think. Indeed, there was nothing else to do. This was when Larius Lollius the painter took stock, having an enforced pause in his desperate journey. Sheltered with his daughter at least temporarily, he assessed their plight.

Now, Larius faced the likelihood that he would not survive this. Standing alone in a peristyle of somebody else’s villa as it slowly filled with still-hot magma, he wondered whether they would be forced to simply stop right here. It felt too unsafe. What choice was there? As far as he had seen downstairs by wavering lamplight, this place once possessed fine decoration of the kind he had spent his adult life creating. It had been turned over to industry and barely lived in, or at least not used for the leisured life its first owners must have planned. But it was being swallowed up in filth, filth he could taste, filth that had made his daughter cough her lungs out, and which was stifling him too. He felt the grit in his teeth, dust sticky on his skin and clothes, debris clustered in his hair. Oplontis was slowly being buried. Anyone who stopped moving would be buried too.

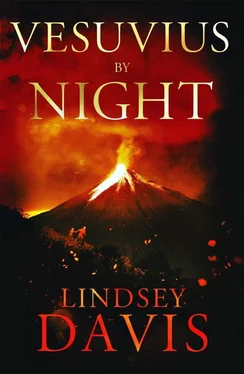

Now, looking out and up, Larius could see Vesuvius. The coast below the mountain was shrouded in impenetrable dark, while huge flames of different colours rent the high slopes and the sky above the volcano. Sometimes there were single streaks of light, sometimes a snaking trail, sometimes whole showers of pyrotechnics shaken out through the billowing blackness. All around grumbled the noise of whatever was happening far underground. Innumerable farms must have been destroyed. Crops and vineyards were buried, hundreds of animals were dead. People too. Even those who had managed to stay alive until now were facing cataclysmic danger.

This was when Larius cursed his fate, and he cursed from his soul, using the worst words he knew. Here he was, an eyewitness. He wanted to paint this. Generations of painters would strike awe in viewers with their Vesuvius by Night . For them would be movement and torment, fire and darkness, horror and suggested noise. They could position tiny figures, stricken by fear, contrasted against the enormity of ungovernable natural forces. Many would achieve this from imagination alone, for you cannot force a volcano to erupt when you need a model. He could have done it from life. But Larius knew, recreating this dramatic scene would never be for him.

He could only stare, as he thought of his own short life and his family – then in his wry way accepted the aching pain of so much wasted opportunity. He was a fatalist. He knew, tonight, this was the end of everything for him.

He went back to his daughter and squatted beside her, elbows on knees, face buried in his hands. All over the area people took that pose. It was a position in which they could rest – but also the posture of despair.

Nonius proceeds towards magnificent prosperity. Can a man with no conscience really be happy? Of course he can.

Back in Pompeii, there had been a lull caused by the combination of nightfall and the increased ferocity of falling pumice. No one now ventured onto the streets. Pale ash lay to chest height; it was rising several inches every hour. If, from his resting place at Oplontis, Larius had given any thought to his former subtenant, he might have assumed Nonius would still be tirelessly attempting to rob people. But Nonius had gone. It was what men did, those with an instinct for self-preservation – or those protected by the gods.

The good people of Pompeii had entrusted themselves to many deities’ protection that day. Venus Pompeiana, their town’s chosen dedicatee, whose huge half-built temple towered over the Forum, stared out dramatically to the turbulent sea. Bona Dea, the Good Goddess, received many frightened pleas. Egyptian Isis. The goddess Fortune herself, who leaned on a rudder with which she governed human destiny. Apollo, light-hearted, talented past patron of the city. Giant phaluses that symbolised life, small ones with ridiculous wings or hanging bells. Jupiter the king of all… Despite amulets, signet rings, statuettes, pleadings, vows and prayers, the gods with their heartless, ruthless neutrality lent no help.

Fortune helps those who help themselves, thought Nonius, the cheery villain who had been so tenaciously helping himself to other people’s property.

As the eruption started he had worked, harder than ever in his life, continuing through as much of the day as he could. Treading the ash, peering through the murk, forcing open half-blocked doors as he battered his way in to find secreted riches. Luckily in the best houses, their valuables had been displayed in the atrium, easy to find unless owners had snatched up their treasure and inconsiderately run off with it – ignoring the need to supply Nonius.

Enough was left for him. People had locked up, intending to come home tomorrow. People buried stuff, yet left behind their spades. People dropped things as they ran. As the day had grown worse and those who remained from choice or helplessness cowered in ever deeper hiding places, Nonius coughed and staggered, yet he obtained many delightful sets of silver drinking wares: trays, jugs, pairs of cups, mixing bowls, snack saucers, spoons and ladles, little tripod stands to place your drink upon, even egg cups. He gathered dishes and jugs that were designed for religious offerings. He snatched bags of coins. He took jewellery: chains, ear-rings, bangles, finger rings, pendants, brooches, filigree hairnets. If he found no gold, he did not reject silver, alloys, even iron if it looked to have a value.

Then as the day went on, before ash filled gardens and made doors quite immovable, before he was brought to a standstill, Nonius departed from Pompeii. His sense of timing remained sharp. While roofs and balconies began to collapse all across the town, he was travelling out. He saw fires – and saw the falling pumice quench them. He heard screams and cries for help but he kept going. He was safe by the time the ceilings smashed down in the house where Larius had once worked. By then so much ash had descended, the newly decorated plasterwork landed not on the mosaic floor but on fully four feet of debris that had already poured into the house, the bakery, the garden, the stables full of panicked beasts. The baker’s hog and poultry were still on the cooking bench, definitely overcooked.

While others were trapped inside buildings or buried in the streets, Nonius escaped. While people and animals died in Pompeii, he lived. It could have been different. If Fortune was fair, Nonius would have been stuck in the doomed town. He might even have found salvation. If endings were truly cathartic in real life, he could have carried out some great act of selfless sacrifice. He might have saved someone else, or at least offered comfort to somebody deserving.

Читать дальше