And so I began this book, an account of those who have fallen in their pursuits. Whole books could be unearthed on each of their lives--and I hope that happens someday. But for now, these excavations may suffice.

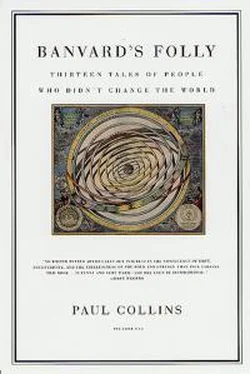

BANVARD'S FOLLY

BANVARD'S FOLLY

Mister Banvard has done more to elevate the taste for fine arts, among those who little thought on these subjects, than any single artist since the discovery of painting and much praise is due him. --The Times of London The life of John Banvard is the most perfect crystallization of loss imaginable. In the 1850's, Banvard was the most famous living painter in the world, and possibly the first millionaire artist in history. Acclaimed by millions and by such contemporaries as Dickens, Longfellow, and Queen Victoria, his artistry, wealth, and stature all seemed unassailable.

Thirty-five years later, he was laid to rest in a pauper's grave in a lonely frontier town in the Dakota Territory. His most famous works were destroyed, and an examination of reference books will not turn up a single mention of his name. John Banvard, the greatest artist of his time, has been utterly obliterated by history.

What happened?

In 1830, a fifteen-year-old American schoolboy passed out this handbill to his classmates, complete with its homely omission of a 5th entertainment: BANVARD'S ENTERTAINMENTS (to be seen at No. 68 Centre street, between White and Walker.) Consisting of 1/. Solar Microscope 2nd. Camera Obscura 3rd. Punch and Judy 4th. Sea Scene 6th. Magic Lantern Admittance (to see the whole) six cents. The following are the days of performance, viz: Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. Performance to commence at half-past 3 P.m. JOHN BANVARD, Proprietor

Although his classmates were not to know, they were only the first of more than two million to witness the showmanship of John Banvard. Visiting Banvard's home museum and diorama in Manhattan, they might have been greeted by his father, Daniel, a successful building contractor and a dabbler in art himself. His adventurous son had acquired a taste for sketching, writing, and science--the latter pursuit beginning with a bang when an experiment with hydrogen exploded in the young man's face, badly injuring his eyes.

Worse calamities lay in store. When Daniel Banvard suffered a stroke in 1831, his business partner fled with the firm's assets. Daniel's subsequent death left the family bankrupt. After watching his family's possessions auctioned off, John lit out for the territories--or at least for Kentucky. Taking up residence in Louisville as a drugstore clerk, he honed his artistic skills by drawing chalk caricatures of customers in the back of the store. His boss, not interested in patronizing adolescent art, fired him. Banvard soon found himself scrounging for signposting and portrait jobs on the docks.

It was here that he met William Chapman, the owner of the country's first showboat. Chapman offered Banvard work as a scene painter. The craft itself was primitive by the standards of later showboats, as Banvard later recalled: The boat was not very large, and if the audience collected too much on one side, the water would intrude over the low gunwales into their exhibition room. This kept the company by turns in the un-artist-like employment of pumping, to keep the boat from sinking. Sometimes the swells from a passing

steamer would cause the water to rush through the cracks of the weather-boarding, and give the audience a bathing .... They made no extra charge for this part of the exhibition.

The pay proved to be equally unpredictable. But if nothing else, Chapman's showboat gave Banvard ample practice in the rapid sketching and painting of vast scenery--a skill that would eventually prove to be invaluable.

Deciding that he'd rather starve on his own payroll than on someone else's, Banvard left the following season. He disembarked in New Harmony, Ohio, where he set about assembling a theater company. Banvard himself would serve as an actor, scene painter, and director; occasionally, he'd dash onstage to perform as a magician. He funded the venture by suckering a backer out of his life savings; this pattern of arts financing would haunt him later in life.

The river back then was still unspoiled--and unsafe. But the troupe did last for two seasons, performing Shakespeare and popular plays while they floated from port to port. Few towns could support their own theater, but they could afford to splurge when the floating dramatists tied up at the dock. Customers sometimes bartered their way aboard with chickens and sacks of potatoes, and this helped fill in the many gaps in the troupe's menu. But eventually food, money, and tempers ran so short that Banvard, broke and exhausted from bouts with malarial ague, was reduced to begging on the docks of Paducah, Kentucky.

While Banvard was now a toughened showman with several years of experience, he was also still a bright, intelligent, and sympathetic teenager. A local impresario took pity on the bedraggled boy and hired him as a scene painter.

Banvard, relieved, quit the showboat.

It was a good thing that he did quit, for farther downriver a bloody knife fight broke out between the desperate thespians. The law showed up in the form of a hapless constable, who promptly stumbled through a trapdoor in the stage and died of a broken neck. With a dead cop on their hands, the company panicked and abandoned ship; Banvard never heard from any of them again.

While in Paducah, Banvard made his first attempts at crafting "moving panoramas." The panorama--a circular artwork that surrounded the viewer--was a relatively new invention, a clever use of perspective that emerged in the late 1700's. By 1800, it was declared an official art form by the Institut de France. Photographic inventor L. J. Daguerre went on to pioneer the "diorama,"

which was a panorama of moving canvas panels viewed through atmospheric effects. When Banvard was growing up in Manhattan, he could gape at these continuous rolls of painted canvas depicting seaports and "A Trip to Niagara Falls."

Moving into his twenties with the memories of his years of desperate illness and hunger behind him, Banvard spent his spare time in Paducah painting landscapes and creating his own moving panoramas of Venice and Jerusalem.

Stretched between two rollers and operated on one side by a crank, they allowed audiences to stand in front and watch exotic scenery roll by. Banvard could not stay away from the river for long, though. He began plying the Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri rivers again, working as a dry-goods trader and an itinerant painter. He also had his eye on greater projects: a diorama of the "infernal regions" had been touring the frontier successfully, and Banvard thought he could improve upon it. During a stint in Louisville, he executed a moving panorama that he described as "INFERNAL REGIONS, nearly 100

feet in length." He completed and sold this in 1841, and it came as a crowning success atop the sale of his Venice and Jerusalem panoramas.

It is not easy to imagine the effect that panoramas had upon their viewers. It was the birth of motion pictures--the first true marriage of the reality of

vision with the reality of physical movement. The public was enthralled, and so was Banvard: he had the heady rush of an artist working at the dawn of a new media. Emboldened by his early successes, the twenty-seven-year-old painter began preparations for a painting so enormous and so absurdly ambitious that it would dwarf any attempted before or since: a portrait of the Mississippi River.

When we read of the frontier today, we are apt to envision California and Nevada. In Banvard's time, though, "the frontier" still meant the Mississippi River. A man setting off into its wilds and tributaries would only occasionally find the friendly respite of a town; in between he faced exposure, mosquitoes, and, if he ventured ashore, bears. But Banvard had been up and down the river many times now, and had taken at least one trip solo as a traveling salesman. The idylls of river life had charms and hazards, as he later recalled:

Читать дальше