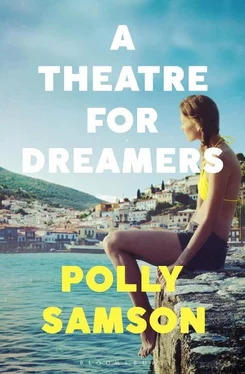

Polly Samson

A THEATRE FOR DREAMERS

‘We are all embarked on our journeys… shooting out on the current, out and away into the wide blue frightening loneliness of freedom, where every man must navigate for himself. Still – the thought is consoling – there are islands.’

– Charmian Clift

‘I’m living. Life is my art.’

– Marianne Ihlen

It’s a climb from the port and I take the steps of Donkey Shit Lane at a steady pace, a heart-shaped stone in my pocket. I walk alone and, though there’s no one to witness, I resist the urge to stop and rest at the standing posts after the steepest part. I watch my step, a stumble can so easily become a fall, a thought that disgusts the gazelle still living within my stiffening body.

The marble slabs shine from centuries of use; the light is pure. Even on a morning gloomy as this, with the sky low enough to blot out the mainland and clouds crowding in on the harbour, these whitewashed streets dazzle.

Two young lads skip, arm in arm, down the steps towards me. I’m as anonymous as a shepherd or a muleteer in Dinos’s ancient tweed jacket, my hands bulging its pockets, my boots comfortably laced. The lines on my face have been deepened by these years in the sun and my hair hasn’t seen dye, or even the hairdresser’s scissors, for who-knows-how-long, but so what? It’s off my face, in a loose tail, the way I’ve always done it. I’m still here, a little bruised, a little dented, but remarkably the girl who first set foot on this island almost sixty years ago remains. I suspect only those who knew me then can see through the thickening patina and it breaks my heart how rapidly the crowd of seers is diminishing.

The call about Leonard came last night. I sat quietly for a while, listened to the owls. I took out my old notebooks, the threepenny jotters that came with me to the island in 1960, found him in my hopeful, curly scrawls. My neck got cricked. The cocks crowed all through the night. I slept badly and woke to a morning crowded by dreams.

The summer visitors are long gone; there’s unrest in Athens as austerity bites, refugees, lost children, fires in the streets. Boats are going out, pulling people from the water. There’s plenty for us to chew over so you might think we’d let the American election slide by. But at the port this morning, as I idled with my one good bitter espresso of the day, watching the mules being led away from the boats with their cargoes, the news of the new President found me. It slithered from the water with the morning pages and spread rapidly like a stench along the agora. There were horrified groans, even from the donkeys, disbelieving splutters from every table, passer-by and boat. For a moment it was a comfort to think that at least Leonard has been spared this.

I stop outside Maria’s shop at Four Corners and listen for voices. I would feel a fool if anyone saw me approaching his front door with my heart-shaped stone and I prepare to walk straight past as I turn the corner from Crazy Street. The street isn’t actually named Crazy but something that sounds similar and that’s what we heard when Leonard came fresh from the notary, pulled off his sixpenny cap and landed the deeds to his house beside it on the table, his grin a little bashful at first, self-conscious, like we might all think he was showing off.

Later that day we came armed with borrowed pails and long-handled brushes for whitewash and Leonard had new batteries for the gramophone that he’d placed in the centre of the stone floor. Some of his records had warped like Dali’s clocks and become unplayable but there was Ray Charles and Muddy Waters and a woman singer I liked but whose name I don’t remember. Later still, a fire of lumber among the lemon trees on the terrace, jugs of retsina, a little hashish, dancing. Paint-spattered shorts, brown limbs, bare feet. War babies, most of us even younger than him and him just a cub, really. We lapped up the freedom our elders had fought for and our appetites reached well beyond their narrow, war-shattered shadows.

Was it drugs and contraception that made change seem possible? Was it a conscious revolution? Or were we simply children who craved languor and sex and mind alteration to ease the anxiety that was etched into our DNA, detonating in each of our young brains its own private Hiroshima?

Ha! To my dad I was a bloody beatnik.

We asked little of this island except days sunny and long enough to keep the Cold War from biting, a galloni of wine for six drachmas, and a solid white house for two pounds and ten shillings a month. We paid only lip service to its name: Hydra. A name that means ‘water’ though an ancient earthquake buried its springs and turned it dry but for a few sweet wells.

In Greek myth, the monstrous Hydra is doorman to the Underworld.

‘A many-headed serpent with halitosis so bad it kills with one breath,’ I say when it’s my turn to set a riddle.

Leonard laughs. Someone has a bouzouki, someone else a guitar. There’s ouzo, stars, a slice of moon as thin as the edge of a spoon. Some old brushwood burns with a resinous crackle; our eyes brighten in an explosion of sparks. We grow wilder, smash our glasses to the wall of Leonard’s new house. For luck!

But Marianne, fetching a broom, asks: ‘What is this crazy custom?’ And not one of us – not American or Canadian, not Greek, English, French, Swedish or Czech, not even the Australian brain on stilts that is George Johnston – can come up with an excuse for this rain of broken glass, except that Marianne threw hers first.

I give the stone heart in my pocket a squeeze. I’m trying to remember why they left so soon after he bought his house. Little more than a month, and Marianne’s skipping through my memory and slipping the stone from her hand to mine. I’m guessing November.

A Russian wind with icy breath, waves scattering across the stones of the port, octopus strung like old tights along a boat rope at the jetty. Leonard in his raincoat (yes – blue, though not remotely famous yet), passing his leather case to the boatman, and here comes Marianne, in rain-splotched and rumpled shirt and sailor pants, hefting several large bundles, lithe and quick as a boy. She turns and calls my name; the wind streaks hair across her face.

It’s the first time she’s even looked at me for weeks. ‘No, no. I can’t bear it if you cry.’ She dumps the luggage, comes running back, the rain pretty on her skin. I can’t stop hugging her, I’m so relieved that she doesn’t want to leave on bad terms.

‘Please don’t look so lonely,’ she says, pulling away and closing my fingers around the stone. She tells me it was the first thing Leonard ever gave her. The stone fits in my palm, meat-coloured and marbled with white and mauve. It truly is a heart, and by the way she’s looking at me I know that now she and Leonard are leaving together, I have been forgiven.

Her smile is so sweet, so full of hope. ‘Just when the one in my chest had been pounded to pieces by Axel. He said I could probably use a replacement.’

Marianne’s eyes are blue as summer skies; her hair is the startling sort of blonde. It’s hard to believe she’d ever think of me as a rival.

‘So much has changed, be happy for me, please. My baby boy waits in Oslo but my heart stays here on the island with you until our return… Oh, sweet Erica, you mustn’t cry.’

Leonard offers me his handkerchief and directs my gaze from the wet port and up to the streaming grey and purple mountains. This place has been kind to him. This island. This woman. He’s pointing back the way they came. ‘There is my beautiful house, and sun to tan my maggot-coloured mind…’ He ruffles my hair like you might a little girl’s and tells me he isn’t planning on staying away long.

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)