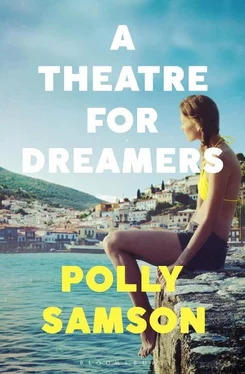

The picture on the book showed her beauty grown wilder, almost in disarray. Between jutting cheekbone and brow, her eyes deep and soulful, bruised almost.

The blurb spoke of an island in Greece, the expatriate life, but now here was my father throwing his shadow across any possibility of sunshine. He was thumbing his braces and, since I was in my dressing gown, completely incapable of looking at me.

‘You’re up early,’ he said, as he stretched his braces back and forth. ‘I thought I’d better check as I didn’t hear you come in last night.’

‘I’ll have your shirt ironed in a jiff. That’s why I set the alarm,’ I lied, yawning and indicating my artfully rumpled bed. He cleared his throat but I got in first. ‘Oh, by the way, I opened this. It came for Mum. It’s from Greece. Do you remember Charmian Clift with the two little children from upstairs? She sent it. It’s her book…’ I prattled on, successfully changing the subject. As devious, it would appear, as my mother.

He gave a sour sniff. ‘Oh, she’s written another book, has she, Lady Airs and Graces, and oh, do have another cocktail . They were Australian, you know, the pair of them…’ The word ‘Australian’ might have been gristle the way he spat it out, and with a final snap of his braces he stalked from my room so that I might finish getting myself ‘decent for work’.

I read Charmian’s book on the bus. I read it in my booth while the yards of punched tapes clicked and clattered through the telex machine. I read of a life of risk and adventure, of a family swimming from rocks in crystal waters, of mountain flowers, of artists admired and poseurs quietly ridiculed, of her husband George (who sounded very witty and clever though I had no memory of ever meeting him at all), of poverty and making-do and local oddballs and saints and the race to prepare a house for the birth of her third child, of an invasion of tourists and jellyfish, an earthquake, of lives spent flying close to the sun. It was little wonder I found myself still lost in its pages well beyond lunchtime and had to be ticked off by Betty, the typing-pool queen. Slipped inside the book was Charmian’s folded card, quite plain.

‘Darling Connie, I wrote this book about our family’s first year here on the island and it’s at last being published in Great Britain. Spread the word in any way you can and most importantly don’t let what I’ve written put you off coming. There’s always a warm welcome for you here from one who firmly believes you still have a chance, Charmian.’

I felt a fluttering of desire as I read her words and an intense craving for that warm welcome and a chance for myself. I couldn’t wait to press Charmian’s book on Jimmy.

Jimmy Jones had long broken his family’s bindings by dropping out of law school and emerging as something brighter and more colourful, more drawn to Jack Kerouac, Sartre and Rilke than to the laws of tort. Jimmy’s wings carried him to a wooden studio at the bottom of Mrs Singh’s garden where a few odd jobs freed him to paint and write poetry and stay in bed until lunchtime.

My thoughts of the island were too exciting for the telephone and Father’s acutely tuned ear. He remained in a foul mood and came up with plenty for me to do around the flat. I wasn’t even allowed to throw out a pair of socks of his where the entire heel had gone. It’s one of my abiding memories of those grey months after Mum died. Being bid to sit in what had been her chair, a pretty one, button-backed and covered in pea-green velvet, her sewing box at my feet, while he sat slurping tea, slumped in his wing chair watching Dixon of Dock Green .

I returned to the subject of Charmian Clift and her book. It was a Tuesday, toad-in-the-hole, his favourite. I’d made gravy and mash so there was a chance he’d be in a better mood.

I was wrong; by the look on his face you’d think something was rancid: ‘Erica, do we really have to talk about your mother’s friends while we’re eating.’

It was hard to believe Mum’s stories of Dad before the war, his handsome smile and dancing feet. His famed quick wit had taken a direct hit at Dunkirk; his get-up-and-go had departed. He used to climb mountains for fun, proposed to her up in the clouds on the peak of the Brecon Beacons. When he was stationed in Cairo he arranged for flowers to be delivered to her every week he was gone. He didn’t stint on paying her dressmaker’s bills, nor for her shampoos and sets. She still dressed every night for his return from the office, though I have no memory of him ever sweeping her out the door to a restaurant or the theatre. Routine was the only thing that kept him sane: his whisky on the tray, ice and silver tongs and the folded newspaper, dinner, then his chair and television while she fluttered in and out with tea and mending.

When we were old enough to be left, she’d escape for the occasional weekend – Great-Aunt Vera’s in Hampshire, Cousin Penny with ‘the problem’ in Wales – but not without punishment on her return. One time he threw a casserole across the kitchen floor and made us leave it until she got back two nights later. He stood over her, soundlessly watching, while she was down on her knees scrubbing the congealed mess with brush and pail. I preferred not to think of her on the floor, flinching at his feet. I decided to punish him, persevered with talking about Charmian.

‘They’d had enough of the rat race. Apparently they went to a different Greek island for a year and Charmian wrote a book about that too. I wonder if Mum ever read it…?’ but now he was pulling off his napkin and scraping back his chair.

‘Don’t bother checking the bookcase, you won’t find it here. No shame at all, these decadents, dragging their children from pillar to post, despising ordinary people, staying up drinking all night with their lah-di-dah artists and poofter friends.’ He wiped his mouth savagely and threw the napkin beside his empty plate.

I went to my room and added a PS to my letter to Charmian Clift. Could she find me a house to rent? And how much would it cost?

And here, at last, is Jimmy, in a slice of light as though straight off the screen, and to my mind more handsome than any film star. He’s opening the door to me with a sly grin. To this day I’ve never known a face so transformed by its smile. Jimmy in repose was rather haunted. But when he smiled it was like the sun coming out and, just as I’d imagined, he was reaching for the zip of my fluffy new primrose jumper.

‘Will you come with me to an island in Greece?’ He was behind me as I climbed the ladder to his bed and answered by sinking his teeth into my bottom.

We did the maths. By the time we joined Bobby and the others at the Gatehouse, we’d given ourselves a year. The band was winding down. I was pleased to see the old sax player was there, a lugubrious veteran in his worn mackintosh with the most soul-rending tone to his playing. Paper moon. A cardboard sea. I thought of Jimmy Jones and me on Charmian’s island, of the seasons turning, extra blankets for our bed, charcoal burning in a brazier. The double bass plinked; the saxophone’s song dwindled to a horizon borne on a few mournful breaths. I took a cigarette from a friend of Bobby’s and perched at the edge of their table, pregnant with plans. Jimmy went to queue at the bar.

Bobby’s new girl was from the art school: his usual type, lean and bird-boned, dressed like an off-duty ballet dancer in cable-knit sweater and tight black Capri pants. She was studiedly monochrome, her face too small for such extravagantly black-fringed eyes, raven hair cut to a delicate nape, the neck of a swan. She sat on a stool in the middle of the group twining and untwining her long legs, saying ‘cool’ and ‘super hep’ without appearing self-conscious.

Читать дальше

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)