Jimmy swivels to check I’m not joking, retrieves the nails from his mouth.

‘There can’t be any wedding at all until I’ve sold my book,’ he says, and I pull a pout and look out of the window to where the breeze has whipped up a whirl of fallen wisteria blossom.

He springs down, the boards barely register his landing, and he tups me under the chin to make me look at him. His eyes are the colour of brown-bottle sea glass when you hold it up to the sun, amber flecked with gold.

‘I’m afraid it would be the final straw. My mother wouldn’t send another penny.’ And he flutters his dark lashes in a Mummy’s poppet sort of a way though really he hates to talk about his mother sending money.

‘But I quite fancy a full-immersion baptism,’ I say and he chuckles, his fingers starting on my buttons.

‘The priests will enjoy it, that’s for sure,’ he says with a lecherous grin. ‘They insist on full nakedness, you know…’ I’ve given up wearing bras and he feigns surprise as he pulls open my shirt.

‘Ah, yes. I reckon we could drum up some support from that bishop at Profitis Elias, “Come, come, my child. That’s right now, shed your sins…”’ and because Jimmy’s got the gift of mimicry and a rubber face to go with it I can’t help but laugh.

The original plan had been to get out of town along the clifftop to Vlychos. There’s a good and wide shingle beach there, turquoise waters, some scrubby pines for shade, enough to accommodate the whole crowd now we’re so outnumbered by the grand Hydriot families and their Athenian scions. There are brass bands and children’s processions. The bells will keep tolling until Vespers when the great Admiral’s heart is due to be processed through the streets in its gold casket.

Greek and Hydriot flags honour him from the corners of houses, water-taxis putt-putt by, low in the water with families and picnics heading for the less-inhabited coves. We see Bim and Demetri waving from Manos’s boat, hanging off the side and posing like film stars in their white shirts and dark glasses. Madam Pouri’s donkey-boy passes in a blue cap, his beasts laden with hampers and blue parasols and blue beads and silver bells that jingle on their reins.

At the point where the road peters out to a dirt track and the land dips away to the sea, we find Cato. Many times I have been drawn to this place at the crest of this gentle gully. The slopes are terraced, there are grazing sheep, stripes of golden barley, in the dip a shepherd’s hut among a grove of olive trees, the only building for as far as the eye can see. There’s a low crumbling wall to sit on and I can blur the blue triangle of sea between the rocky mountain and the rusty hill and no one ever passes or interrupts me.

At first we think the cries are a hawk circling overhead but it’s hard to be certain. Cockerels are crowing and a donkey is making a racket. Dionysus, the rubbish collector, rarely makes it to this part of the island and we follow the faint mewling to where the stench is almost overwhelming. There’s a fetid heap of old cans and rotting cabbage, bursting bags, fermenting melons, eggshells. Flies frenzy around half a ribcage and Jimmy pulls his T-shirt to cover his mouth, cocks his ear and dives for a sack.

‘Oh good God,’ he says as he sets it on the ground, and we see something squirming inside. I drop to my knees to pull at the rope. The cat’s mouth is a piteous pink triangle. Its sparse black coat is bare in patches and the poor thing is unable to open its eyes because they are glued together with gunk.

Jimmy is kicking up a red and glittering sandstorm. ‘What sort of a bastard does this to a cat?’

He unscrews our canteen. The cat’s tongue is lapping at the water and I’m astonished that it manages to purr. Jimmy wets the corner of his handkerchief to bathe its eyes but has to stop when it mewls and tries to crawl away because we aren’t sure if they are crusts or scabs.

There isn’t a vet on the island, as far as we know. Jimmy makes him a nest of his T-shirt and we head back to port with ‘Cato’ in our basket.

Charmian knows what needs to be done. She’s in her kitchen, stirring something that smells delicious and garlicky over the charcoal, her face shiny from the heat. The table is laid, a bunch of wild honeysuckle we picked on our way back from Marianne’s in a jug at the centre. Zoe is folding napkins and there’s chatter and glasses and children’s laughter from the courtyard. Max runs in and out with his tongue lolling and his tail wagging, more pleased about the guests than his mistress appears to be. She’s pulling the tea towel from her shoulder to wipe her face, and I notice that an uncharacteristic attempt at eye make-up has smudged, making her look more tired and worried than ever. The last thing she needs is a mangy cat.

She lifts little Cato out of the basket and holds him, wriggling to the window. His coat is matted with sores but already I can see the fine creature he will become.

‘Everyone who comes here ends up with a cat,’ she says. ‘It looks like this young man has found you – if the tragic mite survives, that is.’ She sends Jimmy off, tells him to run to Rafalias’s pharmacy for a small-sized hypodermic and iodine tincture.

‘His best chance is to give him a course of George’s streptomycin. You’ll have to inject a tiny dose for the next few days. Don’t worry, I’ll show you how.’ She’s checking behind his ears. ‘And you’ll need benzoate to deal with these fleas too.’ She folds up a blanket on the bench and from her cooking pot spoons out a lump of meat and blows on it before feeding it to him in tiny pieces.

‘He’s a nice cat,’ she says. ‘Though the Greeks say a black cat is unlucky in the morning.’

A man is standing in the doorway watching her. He is small and wiry with a reedy voice: ‘I’ve been sent in for a refill.’ His face is ruddy enough to clash with his sandy hair, and he’s waving an empty jug in his hand. From behind him I hear a woman, American, a boomer. ‘Hey, Charlie, find out how much longer Charmian intends to be with the food. Tell her we’re all getting too sloshed out here.’

‘It’s thirsty work keeping up with George. I’d do well to remember his reputation at the press club,’ the man says, and as Charmian reaches to take the jug from him he grasps her by the waist and spins her around, stops when he notices me, ‘Crikey, sorry, I’m Charlie…’ and lets her go.

‘Erica’s a talented young writer but she’s yet to show me a word she’s written,’ Charmian tells him – rather cruelly, I think. I start to object but they’re not listening to me. Charles’s eyes are fixed on Charmian and his fingers are flexed as though he still has her in his grip.

Cato needs drops put in his eyes and ears. Now his eyes are unglued he gazes up at us from a box at the foot of our bed, as love-struck as Titania waking from her dream. We stand there soppy as new parents over a crib.

Though it’s hard to tear ourselves away, we leave him with a mashed sardine and catch the tail-end of the candle-bearers solemnly intoning as they wind through the lanes from the monastery with the Admiral’s heart in its casket.

We foreigners gather at the tables in front of Katsikas and across the alley at Tassos. Many splendid yachts have been shoehorned into the harbour and there are uniformed stewards and tables on decks laid with silver service and napery.

Marianne and Leonard arrive with the baby in his pram. Demetri and Carolyn look on a little anxiously as their toddler enthusiastically lifts out baby Axel and totters around with him in her arms like a doll.

Читать дальше

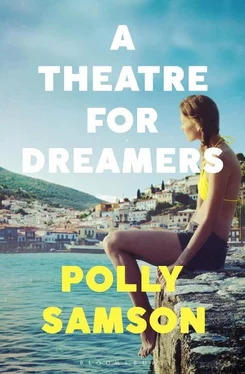

![Джон Макдональд - Wine of the Dreamers [= Planet of the Dreamers]](/books/430039/dzhon-makdonald-wine-of-the-dreamers-planet-of-thumb.webp)