“Robins are elegant,” she told me, “a good omen, a reminder of the special things we have right in front of us.” She hugged me tight.

But now, she stayed home alone and rarely had the energy to talk, even to me.

Just then, Mrs. Gustafson went to her mailbox, and I crossed the brown strip of grass that separated us. She held a letter to her chest.

“Who’s it from?”

“My friend Lucienne in Chicago. We’ve written to each other for decades. She and I came over on the ship together—three unforgettable weeks from Normandy to New York.” She regarded me. “Is everything all right?”

“I’m fine.” Everyone knew the rules: Don’t draw attention to yourself, no one likes a show-off. Don’t turn around in church, even if a bomb goes off behind you. When someone asks how you are, say “fine,” even if you’re sad and scared.

“Would you like to come over?” she asked.

I plunked my backpack in front of her shelves. There were books up and down, but only three photos, small as Polaroids. At my house, we had more pictures than books (the Bible, Mom’s field guides, and an encyclopedia set that we’d found at a garage sale).

The first photo was of a young Marine. He had Mrs. Gustafson’s eyes.

She moved to my side. “My son, Marc. He was killed in Vietnam.”

Once, when I was handing out bulletins at church, a flock of ladies landed near the basin of holy water. Just as Mrs. Gustafson entered, Mrs. Ivers whispered, “Tomorrow’s the anniversary of Marc’s death.” Shaking her head, old Mrs. Murdoch replied, “Losing a child, nothing worse. We should send flowers or—”

“You should stop gossiping,” Mrs. Gustafson snapped, “at least at Mass.”

The ladies dipped trembling fingers into the holy water, quickly made the sign of the cross, and slunk to their pews.

Running my hand over the top of the picture frame, I said, “I’m sorry.”

“As am I.”

The sorrow in her voice made me uneasy. No one ever came to visit her. Not her in-laws, not her French family. What if everyone she’d ever loved was dead? She probably didn’t want me here, dredging up her losses. I moved to pick up my backpack.

“Would you like a cookie?” she asked.

In the kitchen, I grabbed the biggest two on the plate and gobbled them down before she touched hers. Thin and crunchy, the sugar cookies were wrapped in the shape of a miniature spyglass.

She’d just finished the first batch, so over the next hour I helped roll out the rest. I appreciated that she didn’t say anything about Mom. Not, “We miss your mother at the PTA, tell her everyone has to pull their weight.” Or, “Nothing wrong with her that a pork roast couldn’t fix.” Silence had never felt so good.

“What are these cookies called?” I asked as I grabbed another.

“ Cigarettes russes . Russian cigarettes.”

Communist cookies? I put it back on the plate. “Who taught you to make them?”

“I got the recipe from a friend who served them when I delivered books.”

“Why couldn’t she get her own books?”

“She wasn’t allowed in libraries during the war.”

Before I could ask why not, there was a pounding at the door. “Mrs. Gustafson?”

It was Dad, which meant it was six o’clock—dinnertime, and I was in trouble. Wiping the crumbs from my mouth, I prepared my case. Time slipped by, I had to stay to help finish…

Mrs. Gustafson opened the door, and I expected hurricane Dad to rain down.

His eyes were wide, his tie crooked. “I’m taking Brenda to the hospital,” he said to Mrs. Gustafson. “Can you look after Lily?”

I wanted to say I was sorry, but he rushed off, not waiting for a response.

CHAPTER 3

Odile

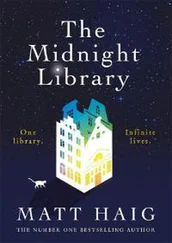

PARIS, FEBRUARY 1939

THE SHADOW OF Saint-Augustin church loomed over Maman, Rémy, and me as we set forth from yet another dull Sunday service. Released from the oppressive grasp of incense, I sucked in icy gales of air, relieved to be away from the priest and his gloomy sermon. Maman prodded us along the sidewalk, past Rémy’s second favorite bookshop, past the boulangerie with the broken-hearted baker who burned the bread, through the threshold of our building.

“Which one is it today, Pierre or Paul?” she fretted. “Whoever he is, he’ll be here any minute. Odile, don’t you dare scowl. Of course, Papa wants to get to know these men.… Not all of them work at his precinct. One might be a perfect suitor for you.”

Another lunch with an unsuspecting policeman. It was awkward when a man showed an interest in me, mortifying when he showed none.

“And change into your blouse! I can’t believe you wore that faded smock to church. What will people think?” she said before rushing to the kitchen to check on the roast.

In the foyer, at the mirror with the chipped gilding, I re-braided my auburn hair; Rémy ran a dab of barber cream through his unruly curls. In French families, Sunday lunch was a ritual every bit as sacred as Mass, and Maman insisted that we look our best.

“How would Dewey classify this lunch?” Rémy asked.

“That’s easy—841. A Season in Hell .”

He laughed.

“How many underlings has Papa invited so far?”

“Fourteen,” he said. “I bet they’re afraid to tell him no.”

“Why don’t you have to go through this torture?”

“Because no one cares when men get married.” With an impish grin, he snatched my scarf and pulled the scratchy wool over his head, knotting it under his chin the way our mother did. “ Ma fille , women have a short shelf life.”

I giggled. He always knew how to cheer me up.

“The way you’re going,” he continued in Maman’s shrill manner, “you’ll be on the shelf forever!”

“A library shelf, if I get the job.”

“ When you get the job.”

“I’m not sure…”

Rémy slipped off the scarf. “You have a library degree, you speak English fluently, and you got high marks at your internship. I have faith in you; have faith in yourself.”

A knock at the door. We opened it to find a blond policeman in a peacoat. I braced myself—last week’s protégé had greeted me by rubbing his greasy jowls against my face.

“I’m Paul,” this one said. He barely touched his cheeks to mine.

“Pleasure to meet you both,” he said as he shook Rémy’s hand. “I’ve heard good things about you.”

He seemed sincere, but I had trouble believing Papa had said anything remotely positive about either of us. All we heard about were Rémy’s dismal grades (Yet he was best debater in his law class!) and my lackluster housekeeping (“How can you sleep on a bed that has books all over it?”).

“I’ve looked forward to today all week,” the protégé told Maman.

“A home-cooked meal will do you good,” she said. “We’re glad you’re here.”

Papa thrust his guest into the armchair near the fireplace, then served the aperitif (vermouth for the men, sherry for the women). While Maman flitted from the seat near her beloved ferns to the kitchen, making sure the maid carried out her instructions, Papa presided from his Louis XV–style chair, his broom-shaped mustache sweeping assertions from his mouth. “Who needs these chômeurs intellectuels ? I say let the ‘intellectual unemployed’ compose their prose while working in the mines. What other country distinguishes between smart loafers and dim ones? My tax money at work!” Each Sunday, the suitor changed; Papa’s long-winded lecture never did.

Once again, I explained, “No one’s forcing you to support artists and writers. You can choose ordinary postage stamps or those with a small surtax.”

Next to me on the divan, Rémy crossed his arms. I could read his mind: Why do you bother?

Читать дальше

![Джанет Скеслин Чарльз - Библиотека в Париже [litres]](/books/391555/dzhanet-skeslin-charlz-biblioteka-v-parizhe-litres-thumb.webp)