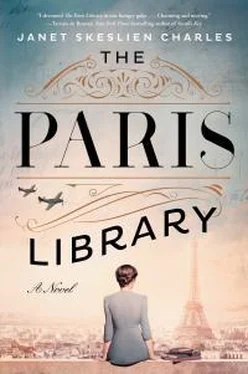

“You do read, don’t you?”

Papa often complained that my mouth worked faster than my mind. In a flash of frustration, I responded to Miss Reeder’s first question.

“My favorite dead author is Dostoevsky, because I like his character Raskolnikov. He’s not the only one who wants to hit someone over the head.”

Silence.

Why hadn’t I given a normal answer—for example, Zora Neale Hurston, my favorite living author?

“It was an honor to meet you.” I moved to the door, knowing the interview was over.

As my fingers reached for the porcelain knob, I heard Miss Reeder say, “ ‘Fling yourself straight into life, without deliberation; don’t be afraid—the flood will bear you to the bank and set you safe on your feet again.’ ”

My favorite line from Crime and Punishment . 891.73. I turned around.

“Most candidates say their favorite is Shakespeare,” she said.

“The only author with his own Dewey Decimal call number.”

“A few mention Jane Eyre .”

That would have been a normal response. Why hadn’t I said Charlotte Brontë, or any Brontë for that matter? “I love Jane, too. The Brontë sisters share the same call number—823.8.”

“But I liked your answer.”

“You did?”

“You said what you felt, not what you thought I wanted to hear.”

That was true.

“Don’t be afraid to be different.” Miss Reeder leaned forward. Her gaze—intelligent, steady—met mine. “Why do you want to work here?”

I couldn’t give her the real reason. It would sound terrible. “I memorized the Dewey Decimal system and got straight As at library school.”

She glanced at my application. “You have an impressive transcript. But you haven’t answered my question.”

“I’m a subscriber here. I love English—”

“I can see that,” she said, a dab of disappointment in her tone. “Thank you for your time. We’ll let you know either way in a few weeks. I’ll see you out.”

Back in the courtyard, I sighed in frustration. Perhaps I should have admitted why I wanted the job.

“What’s wrong, Odile?” asked Professor Cohen. I loved her standing-room-only lecture series, English Literature at the American Library. In her signature purple shawl, she made daunting books like Beowulf accessible, and her lectures were lively, with a soupçon of sly humor. Clouds of a scandalous past wafted in her wake like the lilac notes of her parfum . They said Madame le professeur was originally from Milan. A prima ballerina who gave up star status (and her stodgy husband) in order to follow a lover to Brazzaville. When she returned to Paris—alone—she studied at the Sorbonne, where, like Simone de Beauvoir, she’d passed l’agrégation , the nearly impossible state exam, to be able to teach at the highest level.

“Odile?”

“I made a fool of myself at my job interview.”

“A smart young woman like you? Did you tell Miss Reeder that you don’t miss a single one of my lectures? I wish my students were as faithful!”

“I didn’t think to mention it.”

“Include everything you want to tell her in a thank-you note.”

“She won’t choose me.”

“Life’s a brawl. You must fight for what you want.”

“I’m not sure…”

“Well, I am,” Professor Cohen said. “Think the old-fashioned men at the Sorbonne hired me just like that? I worked damned hard to convince them that a woman could teach university courses.”

I looked up. Before, I’d only noticed the professor’s purple shawl. Now I saw her steely eyes.

“Being persistent isn’t a bad thing,” she continued, “though my father complained I always had to have the last word.”

“Mine too. He calls me ‘unrelenting.’ ”

“Put that quality to use.”

She was right. In my favorite books, the heroines never gave up. Professor Cohen had a point about putting my thoughts in a letter. Writing was easier than speaking face-to-face. I could cross things out and start over, a hundred times if I needed to.

“You’re right…,” I told her.

“Of course I am! I’ll inform the Directress that you always ask the best questions at my lectures, and you be sure to follow through.” With a swish of her shawl, she strode into the Library.

It never mattered how low I felt, someone at the ALP always managed to scoop me up and put me on an even keel. The Library was more than bricks and books; its mortar was people who cared. I’d spent time in other libraries, with their hard wooden chairs and their polite “ Bonjour , Mademoiselle. Au revoir , Mademoiselle.” There was nothing wrong with these bibliothèques , they simply lacked the camaraderie of real community. The Library felt like home.

“Odile! Wait!” It was Mr. Pryce-Jones, the retired English diplomat in his paisley bow tie, followed by the cataloger Mrs. Turnbull, with her crooked blue-gray bangs. Professor Cohen must have told them I was feeling discouraged.

“Nothing is ever lost.” He patted my back awkwardly. “You’ll win the Directress over. Just write a list of your arguments, like any diplomat worth his salt and pepper would.”

“Quit mollycoddling the girl!” Mrs. Turnbull told him. Turning to me, she said, “In my native Winnipeg, we’re used to adversity. Makes us who we are. Winters with temperatures of minus forty degrees, and you won’t hear us complain, unlike Americans.…” Remembering the reason she’d stepped outside—an opportunity to boss someone—she stuck a bony finger in my face. “Buck up, and don’t take no for an answer!”

With a smile, I realized that home was a place where there were no secrets. But I was smiling. That was already something.

Back in my bedroom, no longer nervous, I wrote:

Dear Miss Reeder,

Thank you for discussing the job with me. I was thrilled to be interviewed. This library means more to me than any place in Paris. When I was little, my aunt Caroline took me to Story Hour. It’s thanks to her that I studied English and fell in love with the Library. Though my aunt is no longer with us, I continue to seek her at the ALP. I open books and turn to their pockets in the back, hoping to see her name on the card. Reading the same novels as she did makes me feel like we’re still close.

The Library is my haven. I can always find a corner of the stacks to call my own, to read and dream. I want to make sure everyone has that chance, most especially the people who feel different and need a place to call home.

I signed my name, finishing the interview.

CHAPTER 2

Lily

FROID, MONTANA, 1983

HER NAME WAS Mrs. Gustafson, and she lived next door. Behind her back, folks called her the War Bride, but she didn’t look like a bride to me. First of all, she never wore white. And she was old. Way older than my parents. Everyone knows a bride needs a groom, but her husband was long dead. Though she spoke two languages fluently, for the most part, she didn’t talk to anyone. She’d lived here since 1945, but would always be considered the woman who came from somewhere else.

She was the only war bride in Froid, much like Dr. Stanchfield was the only doctor. I sometimes peeked into her living room, where even her tables and chairs were foreign—dainty like dollhouse furniture with sculpted walnut legs. I snooped in her mailbox, where letters from as far away as Chicago were addressed to Madame Odile Gustafson. Compared to the names I knew, like Tricia and Tiffany, “Odile” seemed exotic. Folks said she came from France. Wanting to know more about her, I studied the encyclopedia entries on Paris. I discovered the gray gargoyles of Notre-Dame and Napoleon’s Arch of Triumph. Yet nothing I read could answer my question—what made Mrs. Gustafson so different?

Читать дальше

![Джанет Скеслин Чарльз - Библиотека в Париже [litres]](/books/391555/dzhanet-skeslin-charlz-biblioteka-v-parizhe-litres-thumb.webp)