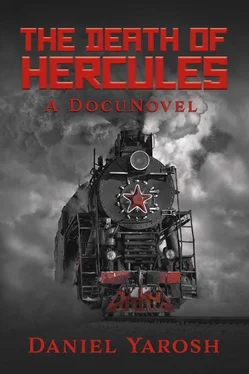

Daniel Yarosh

THE DEATH OF HERCULES

A DocuNovel

The opposite of good is not evil. The opposite of good is chaos.

Evil is an organizing force that arranges before it the good scattered about the world. But in chaos even good turns on itself. The time of chaos is usually briefer and more brutal than when either good or evil is ascendant, and a coherent story is not often found in the confusion. But chaos almost always ends in change. Our story is about a just such a time: the winter of 1918, after World War I had ended. To many the formal world had collapsed, and to others all things were possible.

French Premier and Minister of War Georges Clemenceau had just been in Lille, on the road from Paris to Calais in the heartland of Flanders, in October 1918. At La Citadelle, the old pentagon-shaped army outpost hovering over the central city, he had enthusiastically congratulated the exhausted troops who had only recently recaptured the city. In this great fortress build by the Marquis Vauban, across from the Roman arch guarding the road to Paris, those who were neither gassed nor shot gathered to hear the man they called The Tiger. They limply stood about or sat on the ground, numb from a scale of killing and destruction for which they had not been prepared by stories from their fathers. Their dark gray woolen uniforms, with muddy ankle wraps, added little color to the damp stone walls. More than people and things were destroyed, but also expectations. Yet the job was not finished, The Tiger had told them. He exhorted them to push for a final victory for France. They roused themselves to roar a cheer as best they could and looked to the mess for a warm meal. Later, below in the vieille ville, in the central square of Place Rihour, Clemenceau greeted an ecstatic crowd of civilians recently liberated from four years of German occupation.

One month later still, on November 11, 1918, the Armistice ending the Great War was signed in the nearby forest of Compiègne. Lille was in revelry. The victory unleashed a nervous celebration which continued for weeks. The town drew soldiers from all the Allied armies to its beer halls and bistros that flanked the textile mills and lace finishing shops in the working district.

Max Shertok was the first of the brothers to rendezvous at the Roman Arch across from The Citadel, at 4 pm on the second Sunday after declaration of the Armistice, as the three Shertok brothers had agreed. He had completed repairing the last few motorcycles and personnel carriers for shipment back to the States before taking a two-day leave to meet his siblings. As a mechanic in the Big Red One of the US Army, the End of the War meant fixing at a much more leisurely pace the blown pistons and seized engines that found their way back to his shop. As long as he had the officers’ transports set for the week, they wouldn’t miss him for a few days.

He stuck his big hands deep into the pockets of his woolen overcoat, hunched his shoulders to bring the upturned collar against his ears, and leaned against the marble arch, watching the occasional cars and military trucks go by. Although not tall, he was wiry and strong, with a red-haired complexion and light blue piercing eyes. A mechanic during the Great War was not so far removed from a Civil War blacksmith. If a gear broke, he might be able to replace it from spare parts or from another machine. But if an axel broke, he reworked and welded the original parts with little more than shaped iron-bar tools, an anvil and a good fire. He already had the tough and cold-eyed logic of an engineer, having finished three years of apprenticeship and a year of World War by then.

Finally, a mud-caked American artillery transport slowed, then stopped along the road, and the canvas backdrop lifted enough for Saul Shertok to hop out. He waved to his comrades as they drove off and then turned his dour smile on his younger brother Max. He had closely cropped reddish-blond hair and the same light blue eyes and lean frame as Max. The boys embraced and patted each other on the back, part in joy of family reunion and part in wonderment that they had both survived unscathed. In truth Saul had been in much greater danger. He had been a student in the University of Minnesota agriculture department before he enlisted, and the closest the Army could make use of his talents was in the 102nd field artillery, herding an army mule that pulled a 75-mm gun along the front in the Meuse District. He would say later that it was hard to tell who the greater enemy was, the Germans that shelled Verdun or the damned mule that would not move.

“Where’s Jules?” Saul said to Max, as he reached into his coat for a cigarette. He offered one to Max, and they both inhaled the cold November air with their smoke.

“I wrote him the same as you. He’ll be here,” Max answered.

“They treat you like a mensch in that grease pit?” Saul asked Max, part kidding and mostly protective of his younger brother. He flicked an ash in disgust. The Big Red One had a reputation for treating Jews badly, and new immigrants even worse. They wouldn’t give Max any slack if he couldn’t keep up with their demands.

“I do OK,” Max nodded. “Mostly the stuff is too busted for fixing, so we take them for scrap and parts. You should see what drek they bring in! I tell them they should bury it.” Max looked up. “And you, you still shlepping that donkey around?” He immediately regretted saying it, since it came out too insulting when he only meant to tease. Saul was sensitive about wasting his talents, especially in the artillery, but he covered it with bravado.

“I’m tired of looking at both ends of that filthy beast – last week on the road from Albert I had to light a fire under his tail to get him out of a mudhole! God never made a stupider creature!” Saul never mentioned in conversation or his letters about the shelling, the unbearable shock and pounding that drove other men to hospital, the risk of being a sitting target for the enemy artillery. He only cursed the mule.

They stubbed out the butts in the damp earth and wrapped their coats tighter against the wind. Finally, around the corner came a roar, a sputter, and Julius Shertok zoomed up to the Roman arch riding an officer’s single-stroke motorcycle. “Max! Saul!” he cried and waved as he cut the engine and kicked down the stand.

The two young soldiers ran up to embrace their older brother. Jules had darker brown hair, handsome features and a muscular body that elicited major attention and minor fear. The brothers hugged and nearly cried now, because it wasn’t complete until they were all together. Max finally pulled away first and circled the bike. “Where did you get this?” he asked, wiping his right eye which teared, maybe from the wind.

“I got a captain some chocolates… and silk.” Julius said with a wink. “He was getting a car to Paris and didn’t need this… on his Frenchie holiday!” He leered at Max and slapped Saul on the shoulder. Julius was a supply sergeant with Blackjack Pershing’s main supply headquarters. He had some business training and a gift for numbers, and at the same time he knew human frailties. He managed to squeeze out every efficiency and turn it into a gift. Sometimes it was for his benefit and he never hesitated. But mostly he gave away what was free, scattering good will around the camp for just that case in which he needed a motorcycle and not many questions.

“Come on – get on!” he waved over his shoulder. “We’ll go down and see what the Krauts like about this town!” Max and Saul climbed on behind Julius. He started the engine and gunned it. The front wheel wobbled as it slowly turned, and the springs strained under the weight of three soldiers. But the bike finally began rolling forward and picked up speed as they headed downhill.

Читать дальше