She couldn’t look at me. She scrunched up her face and stared over at the fields, up at the moon. She scuffed at the dirt.

‘I want to ask you to come but I’d only be taking you to bombs and ma… She won’t let you stay. I know she won’t.’

‘You shouldn’t be going back to that either.’

‘I don’t belong here.’

‘You belong with me.’

‘Always,’ I said, crying despite all my effort. I wiped at my face with my sleeve and said, ‘I’ll write you. About Queen Isabella, Amelia and Scholler. I’ll tell you about the bombs.’

‘And the lizard people.’

‘And the lizard people.’

‘You better,’ she said, frowning at me.

‘I will. Promise.’

‘Wait here,’ she said, and went back into the house. She emerged a moment later and pressed some coins into my hand and gave me a map.

‘Won’t they be mad? I don’t want you to get in trouble.’

‘I’ll be fine.’

I put the map and coins in my bag.

‘I’ll give you my address,’ I said, taking her hand and writing across the back of it. ‘You can write to me while I’m travelling, so it arrives before I’m home. It’ll be like you’re there, waiting for me.’

She didn’t say anything, just made a choking hiccup noise, kissed me, and ran off, disappearing into the house. I stared up at the house and she appeared at the window. The moonlight made her skin glow.

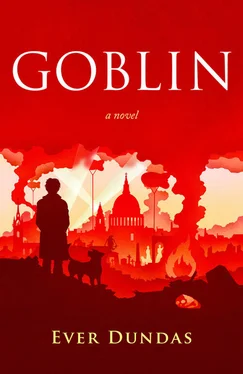

Cornwall, February 1941

We walked along the main road out of town, a skip in my step as I thought of John and those unholy bastards.

‘Holy, Holy, Holy!’ I sang. ‘Corporal Pig, sir! Those fools don’t know what holy is, but we do, we do, CP. All hail the lizards down below. Yes, sir!’

I laughed, thinking of John waking up covered in rabbit insides. I jumped into the air, ‘Yee-hah! We’re on an adventure, CP!’ CP took fright and skittered off the road, half-falling into a bush.

‘Ah, CP, c’mon, c’mon. There’s a war on, CP. How are we supposed to win if you’re all dirty milky?’

We stuck to the main road through the night, but took a sheltered route through the forest as dawn broke.

‘I’m sure they’re glad to see the back of me, CP. But you never know, you never know, and I’m not going back in that old attic, that’s for sure.’

We were well past the outskirts of town and I marked on the map where I thought we were and plotted where we would be heading. Signs had been removed in case of a German invasion, which made finding our way more difficult. I didn’t have much of a plan past getting as far away as possible, and once we were far far away we would hitch lifts, hop on trains.

‘I’m tired out, CP. Some breakfast and a nap is what we need.’

We walked deeper into the forest and settled down at the base of a tree. I rummaged in the bag for food, pushing aside the remains of Monsta. ‘We’ll fix you soon, Monsta,’ I said. ‘You’ll be good as new.’ I gave CP some feed and I had a slice of bread. CP fell asleep and I used him as a pillow, drifting off to the rhythm of his breath.

* * *

I had a nightmare. I was back in that attic, tied to the bed, unable to breathe as they tore Monsta apart. Angel was there and she was one of them.

I woke to the gloaming. I felt sick, unable to shake the nightmare. Corporal Pig had wandered off and I panicked before I saw his pink bulk through the trees. I went to fetch him and found him snuffling amongst the undergrowth, gathering sticks for a nest. ‘I’ll need to tie you up, CP. You can’t go a-wandering. There’s beasts in the forest that will gobble you whole.’

We set off again, trudging along, moving back to the main roads. The sun set in the west and I knew we more or less needed to head north-east, so on we went and I hoped for the best.

* * *

A week into the journey and our supplies were running low.

‘CP,’ I said. ‘If I die, if I starve to death, you can eat me.’

‘Why, Goblin,’ I said, putting on a hoity-toity voice I was sure CP would have if he could speak human, ‘why Goblin-runt-human-child, if I die you can eat me .’

‘Never, CP. Never.’

‘And I’d never eat you Goblin-runt-human-child. It’d be like sucking on a mummy’s corpse all decomposed and gnarled and rotten and skin and bone.’

‘Why thank you, Corporal, thank you very much . Eating you would be much the same. Look at you! Empty fatty folds hanging off your bones. A pig should be rotund, a pig should waddle, head held high as their humongous behind sways this way that way.’

‘Why, thank you very much, Goblin-runt-human-child. So what are we to do about it?’

‘A mission, CP. Into enemy territory.’

That’s when I took the risk of leaving the forests and the fields and headed towards a small village. I tied CP to a tree. I didn’t want the villagers thinking they could eat him for their tea.

‘Look, CP,’ I said, ‘I need to go this mission alone, but there’s danger that lurks round every corner and if a monster or a tiger or a wolf or a fox tries to chew on your skinny bones you do just like you did back home and give ’em a kicking. Right? Just like you used to, CP. I’ll be mighty mad if I come back and you’re a bloody mess. Mighty mad.’

* * *

‘Where’s your ration books?’

‘I lost them.’

The old grocer man looked me up and down.

‘I don’t know you. You one of those refugees?’

‘Evacuee. I live with the Frys,’ I said, remembering a name on one of the doors I passed as I walked through the village.

‘The Frys didn’t take on any refugees.’

‘I can assure you, sir, they did. I am me, I am they, the refugee, evacuee. They took me in. The authorities , sir, said they must. “Don’t you know there’s a war on?” is what the authorities said, and the Frys they had to do their bit or be shamed.’

‘Well, I haven’t heard news of this. When’d you arrive?’

‘Sir,’ I said, ‘you have to help me out,’ I sidled up to him and lowered my voice. ‘The Frys are reluctant guardians, sir, poor parents to I am me the refugee evacuee. Poor parents indeed. But it’s a roof over my head and a bomb-free sky over that roof, so who am I to complain? No, sir, not one to complain. But they’ll give me a thrashing, sir—’

‘I doubt that, young lad. Unless you deserved it.’

‘Well, sir, you see, I lost the ration books.’

‘So you said.’

‘It takes an awful lot of time and fuss to sort that out, sir, and if I go back empty handed… well, you don’t want us to starve, sir. I’m sure you don’t.’

He let out a snort.

‘They got themselves a right one in you, didn’t they? I can tell the likes of you. Weaving tales, spinning words into nets. One day you’ll get in trouble with that mouth, boy. Starving, indeed!’

He shuffled over to the shelves, picking out various bags and tins.

‘The usual, then? I’ll be making a note of it, mind. I’m not getting in trouble on this one.’

‘Yes, sir, of course, sir.’

I watched him and could see there was too much for me and Corporal Pig to carry, so I said, ‘Well, sir, why don’t you make it half the amount. We really don’t need all that, just a bit to tide us over ’til new ration books come in.’

I smiled sweetly and nodded as he paused.

‘Just half?’

‘That’s right. That’ll tide us over.’

I came away with a good supply that would keep CP and I going strong and I hurried past the Frys’ house with my loot, glancing nervously at their door as if they might sense I was off with half their rations.

Читать дальше