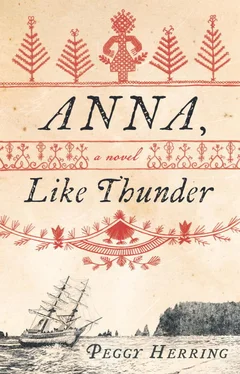

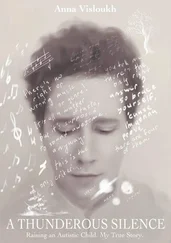

Peggy Herring

ANNA, LIKE THUNDER

For my mother, Irene, and my grandparents,

Anatolii and Marusya, with gratitude

for the stories that got me started

When I told her that her spouse would free the captives only on condition of an exchange for herself, Mrs. Bulygin gave us an answer that struck us like a clap of thunder, an answer we could not believe for several minutes, taking it all for a dream. In horror, distress, and anger, we heard her say firmly that she was satisfied with her condition, did not want to join us, and that she advised us to surrender ourselves to this people.

—TIMOFEI TARAKANOV

{1} 1 Vasilii Mikhailovich Golovnin (English translation by Alton S. Donnelly), The Wreck of the Sv. Nikolai , “The Narrative of Timofei Tarakanov” (Lincoln, Nebraska, University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 59.

You will hear thunder and remember me,

and think: she wanted storms.

—ANNA AKHMATOVA

{2} 2 Anna Akhmatova (English translation by D.M. Thomas), You Will Hear Thunder: Poems by Anna Akhmatova , “You Will Hear Thunder” (Athens, Ohio, Ohio University Press, 1985), 86.

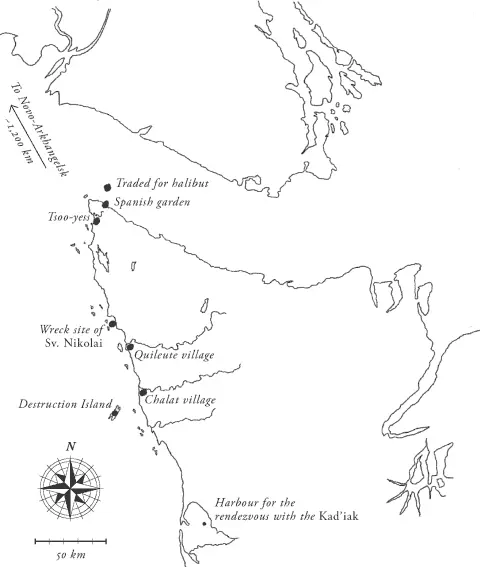

In November 1808, the Russian ship St. Nikolai ran aground off the west coast of the Olympic Peninsula near present-day La Push, Washington. According to records, the twenty-two Russians aboard came to shore and were enslaved and traded among coastal First Nations until the survivors were rescued a year and a half later. One of the Russians was eighteen-year-old Anna Petrovna Bulygina, the wife of the navigator.

There are two written records of this incident. One comes from Russian fur trader Timofei Osipovich Tarakanov, who was the supercargo aboard the ship. After rescue, he related the story of his experiences to Navy Captain V.M. Golovnin, who wrote it down and published it in Russia in 1874. The second is a Quileute oral tradition that was told by elder Ben Hobucket to federal Indian service official Albert Reagan around 1909 and published in 1934. In 1985, the two accounts were published together as The Wreck of the Sv. Nikolai , edited and with an introduction by the late historian Kenneth N. Owens. Despite their origins, there is a remarkable level of concurrence between the two versions.

Anna is a minor character in both accounts, though she plays a pivotal role. During an attempted rescue, she refused help and instead encouraged her rescuers to surrender. This set off a series of events that today illuminate an important period of history on the coast of the Olympic Peninsula.

This novel explores Anna’s decision in the weeks before the event and the months that followed. This fictionalized version of what happened and why diverges at times from the written record, as she witnesses events from a vantage point not considered in historical documents. I’ve tried to remain faithful to the history as I understand it; nonetheless, this remains a work of fiction.

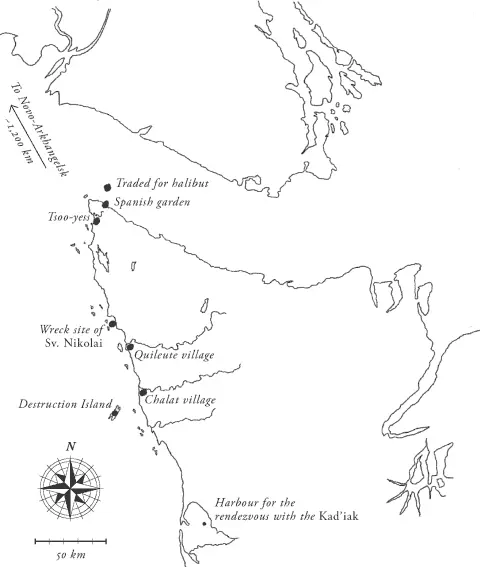

PRESENT-DAY OLYMPIC PENINSULA, WASHINGTON

I can scarcely see my beloved Polaris. The wispy clouds are like the sheerest muslin, and they stretch over the whole of the night sky obscuring the stars. But I keep my telescope pointed at her. If I wait, she may emerge: the brilliant beacon around which the heavens revolve. Navigators call her the North Star or the Ship Star. True amateurs like my father would call her Alpha Ursae Minoris: “alpha” because she is the brightest, and “ursae minoris” because she finds her home in the Little Bear constellation.

She will always be beloved, of course, for her role in guiding explorers and traders for centuries over land and sea. But I adore her for what most don’t know. That she is not one star. Not two. She is three stars. Perhaps more. If not for the renowned astronomers Monsieur William Herschel and Mademoiselle Caroline, his accomplished sister, no one would know that. I aspire to make such discoveries of my own one day.

The brig groans and tilts as she climbs a wave. I wrench the brass telescope from my eye and fumble with my free hand. The bulwark is almost out of reach, but—here, I have it. I clutch the telescope to my chest. The ship tilts in the opposite direction as she slides down the wave and lands with a thud. I stagger. The frigid seawater splashes my face, and I shiver. With my shawl, I wipe the drops from my telescope, hoping no water has seeped through the seams and damaged it. As for my shawl, it’s warm but not my best—grey wool with a peacock-blue fringe that’s almost too pretty for it. If the salt stains it, I hardly care, and besides, nobody will be able to tell.

“Anya!”

My husband strides across the deck. Like the rest of the crew, he is sure on his feet, experienced after so many years working the ships for the Russian-American Company. Roiling seas are no trouble for him, but I’m still learning to live with their caprice.

“What are you doing out here? Come to bed.” Nikolai Isaakovich slips his arm around my waist, and, because it’s dark and the two men on watch can’t see us, I release the bulwark and lean back. He’s warm, and his body shelters me from the wind. His beard scratches my cheek.

“I just wanted one more look,” I say.

He knows about my star log, and that it’s modelled on the published tables my father pores over day and night. In Petersburg I helped my father with his log. Now I have my own, and it will be the first catalogue of the stars ever made along the vast coast that connects Novo-Arkhangelsk to the Spanish colonies in California.

Much to my dismay, there have been many cloudy nights, and the stars have often hidden themselves. There have been many cloudy days, too. Days when the grey sea and the grey sky merge, and the brig crawls along like a cart with a damaged wheel. I’ve not been able to log the stars as much as I’d hoped. So when tonight’s sky looked promising, I tied my cap tight and pinned my shawl high on my neck to keep the cold out so I could extend my time on deck.

My husband releases me, and I latch onto the bulwark again. “Khariton Sobachnikov!” he calls.

“Yes, Commander?” comes the reply from the wheel. He’s the tallest of the promyshlenniki—the sailors, fur traders, and hunters who work for the Russian-American Company—and, because of his height, our main rigger. There’s not a mast or a spar he can’t climb, not a bit of rigging he can’t reach, even when the brig is tilted well over the waves.

He’s also painfully shy. He can barely bring himself to address me, but when forced to, his face turns a livid red as soon as he opens his mouth. I believe it’s because of his manner that he prefers the watch at night, when the rest of us are asleep and he doesn’t have to speak with anybody. I leave him to his work when I’m out on deck, just as he leaves me to mine.

“Everything good?”

“Yes, Commander. The wind’s coming up. But it’s favouring us tonight.”

“And our apprentice? Are you awake?”

“Yes, Commander. I’m over here,” calls Filip Kotelnikov from the bow. Heavy, with a body as round as a kettle and limbs like sticks, he’s sharp and ambitious enough that he’s the only one besides Sobachnikov who’ll volunteer for the night watch. Still, he’s impatient and it irritates my husband, so I doubt his actions will lead where he hopes.

Читать дальше