‘They would be killed!’ Mordred squealed desperately.

The staff was slowly lowered so that it pointed again at Mordred’s face. ‘He promised you what, dear boy?’ Merlin asked.

Mordred squirmed in his chair, but there was no escape from that staff. He swallowed, looked left and right, but there was no help for him in the hall. ‘That they would be killed,’ Mordred admitted, ‘by the Christians.’

‘And why would you want that?’ Merlin inquired.

Mordred hesitated, but Merlin raised the staff high again and the boy blurted out his confession.

‘Because I can’t be King while he lives!’

‘You thought Arthur’s death would free you to behave as you like?’

‘Yes!’

‘And you believed Sansum was your friend?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you never once thought that Sansum might want you dead, too?’ Merlin shook his head. ‘What a silly boy you are. Don’t you know that Christians never do anything right? Even their first one got himself nailed to a cross. That’s not the way efficient Gods behave, not at all. Thank you, Mordred, for our conversation.’ He smiled, shrugged and walked away. ‘Just trying to help,’ he said as he went past Arthur.

Mordred appeared as if he already had the shakes threatened by Merlin. He clung to the arms of the chair, quivering, and tears showed at his eyes for the humiliations he had just suffered. He did try to recover some of his pride by pointing at me and demanding that Arthur arrest me.

‘Don’t be a fool!’ Arthur turned on him angrily. ‘You think we can regain your throne without Derfel’s men?’ Mordred said nothing, and that petulant silence goaded Arthur into a fury like the one which had caused me to hit my King. ‘It can be done without you!’ he snarled at Mordred, ‘and whatever is done, you will stay here, under guard!’ Mordred gaped up at him and a tear fell to dilute the tiny trace of blood.

‘Not as a prisoner, Lord King,’ Arthur explained wearily, ‘but to preserve your life from the hundreds of men who would like to take it.’

‘So what will you do?’ Mordred asked, utterly pathetic now.

‘As I told you,’ Arthur said scornfully, ‘I will give the matter thought.’ And he would say no more. The shape of Lancelot’s design was at least plain now. Sansum had plotted Arthur’s death, Lancelot had sent men to procure Mordred’s death and then followed with his army in the belief that every obstacle to Dumnonia’s throne had been eliminated and that the Christians, whipped to fury by Sansum’s busy missionaries, would kill any remaining enemies while Cerdic held Sagramor’s men at bay. But Arthur lived, and Mordred lived too, and so long as Mordred lived Arthur had an oath to keep and that oath meant we had to go to war. It did not matter that the war might open Severn’s valley to the Saxons, we had to fight Lancelot. We were oath-locked.

Meurig would commit no spearmen to the fight against Lancelot. He claimed he needed all his men to guard his own frontiers against a possible attack from Cerdic or Aelle and nothing anyone said could dissuade him. He did agree to leave his garrison in Glevum, thus freeing its Dumnonian garrison to join Arthur’s troops, but he would give nothing more. ‘He’s a yellow little bastard,’ Culhwch growled.

‘He’s a sensible young man,’ Arthur said. ‘His aim is to preserve his kingdom.’ He spoke to us, his war commanders, in a hall at Glevum’s Roman baths. The room had a tiled floor and an arched ceiling where the painted remnants of naked nymphs were being chased by a faun through swirls of leaves and flowers.

Cuneglas was generous. The spearmen he had brought from Caer Sws would be sent under Culhwch’s command to help Sagramor’s men. Culhwch swore he would do nothing to aid Mordred’s restoration, but he had no qualms about fighting Cerdic’s warriors and that was still Sagramor’s task. Once the Numidian was reinforced by the men from Powys he would drive south, cut off the Saxons who were besieging Corinium and so embroil Cerdic’s men in a campaign that would keep them from helping Lancelot in Dumnonia’s heartland. Cuneglas promised us all the help he could, but said it would take at least two weeks to assemble his full force and bring it south to Glevum. Arthur had precious few men in Glevum. He had the thirty men who had gone north to arrest Ligessac who now lay in chains in Glevum, and he had my men, and to those he could add the seventy spearmen who had formed Glevum’s small garrison. Those numbers were being swollen daily by the refugees who managed to escape the rampaging Christian bands who still hunted down any pagans left in Dumnonia. We heard that many such fugitives were still in Dumnonia, some of them holding out in ancient earth forts or deep in the woodlands, but others came to Glevum and among them was Morfans the Ugly, who had escaped the massacre in Durnovaria’s taverns. Arthur put him in charge of the Glevum forces and ordered him to march them south towards Aquae Sulis. Galahad would go with him. ‘Don’t accept battle,’ Arthur warned both men, ‘just goad the enemy, harry them, annoy them. Stay in the hills, stay nimble, and keep them looking this way. When my Lord King comes’ — he meant Cuneglas — ’you can join his army and march south on Caer Cadarn.’

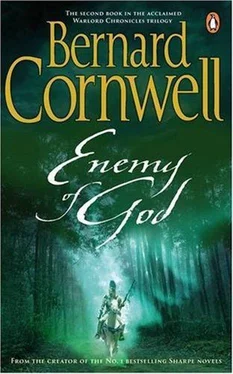

Arthur declared that he would fight with neither Sagramor nor Morfans, but would instead go to seek Aelle’s help. Arthur knew better than anyone that the news of his plans would be carried south. There were plenty enough Christians in Glevum who believed Arthur was the Enemy of God and who saw in Lancelot the heavensent forerunner of Christ’s return to earth; Arthur wanted those Christians to send their messages south into Dumnonia and he wanted those messages to tell Lancelot that Arthur dared not risk Guinevere’s life by marching against him. Instead Arthur was going to beg Aelle to carry his axes and spears against Cerdic’s men. ‘Derfel will come with me,’ he told us now. I did not want to accompany Arthur. There were other interpreters, I protested, and my only wish was to join Morfans and so march south into Dumnonia. I did not want to face my father, Aelle. I wanted to fight, not to put Mordred back on his throne, but to topple Lancelot and to find Dinas and Lavaine. Arthur refused me. ‘You will come with me, Derfel,’ he ordered, ‘and we shall take forty men with us.’

‘Forty?’ Morfans objected. Forty was a large number to strip from his small war-band that had to distract Lancelot.

Arthur shrugged. ‘I dare not look weak to Aelle,’ he said, ‘indeed I should take more, but forty men may be sufficient to convince him that I’m not desperate.’ He paused. ‘There is one last thing,’ he spoke in a heavy voice that caught the attention of men preparing to leave the bath house. ‘Some of you are not inclined to fight for Mordred,’ Arthur admitted. ‘Culhwch has already left Dumnonia, Derfel will doubtless leave when this war is done, and who knows how many others of you will go? Dumnonia cannot afford to lose such men.’ He paused. It had begun to rain and water dripped from the bricks that showed between the patches of painted ceiling. ‘I have talked to Cuneglas,’ Arthur said, acknowledging the King of Powys’s presence with an inclination of his head, ‘and I have talked with Merlin, and what we talked about are the ancient laws and customs of our people. What I do, I would do within the law, and I cannot free you of Mordred for my oath forbids it and the ancient law of our people cannot condone it.’ He paused again, his right hand unconsciously gripping Excalibur’s hilt. ‘But,’ he went on,

‘the law does allow one thing. If a king is unfit to rule, then his Council may rule in his stead as long as the king is accorded the honour and privileges of his rank. Merlin assures me this is so, and King Cuneglas affirms that it happened in the reign of his great-grandfather Brychan.’

Читать дальше