For Kelley, my warp and weft

THE CHILD’S WORLD CHANGED late one afternoon, though she didn’t know it. She lay at the edge of the hazel coppice, one cheek pressed to the moss that smelt of worm cast and the last of the sun, listening: to the wind in the elms, rushing away from the day, to the jackdaws changing their calls from “Outward! Outward!” to “Home now! Home!,” to the rustle of the last frightened shrews scuttling under the layers of leaf fall before the owls began their hunt. From far away came the indignant honking of geese as the goosegirl herded them back inside the wattle fence, and the child knew, in the wordless way that three-year-olds reckon time, that soon Onnen would come and find her and Cian and hurry them back.

Onnen, some leftwise cousin of Ceredig king, always hurried, but the child, Hild, did not. She liked the rhythm of her days: time alone (Cian didn’t count) and time by the fire listening to the murmur of British and Anglisc and even Irish. She liked time at the edges of things—the edge of the crowd, the edge of the pool, the edge of the wood—where all must pass but none quite belonged.

The jackdaw cries faded. The geese quieted. The wind cooled. She sat up.

“Cian?”

Cian, sitting cross-legged as a seven-year-old could and Hild as yet could not, looked up from the hazel switch he was stripping.

“Where’s Onnen?”

He swished his stick. “I shall hit a tree, as the Gododdin once swung at the wicked Bryneich.” But the elms’ sough and sigh was becoming a low roar in the rush of early evening, and she didn’t care about wicked war bands, defeated in the long ago by her Anglisc forefathers.

“I want Onnen.”

“She’ll be along. Or perhaps I shall be the hero Morei, firing the furze, dying with red light flaring on the enamel of my armour, the rim of my shield.”

“I want Hereswith!” If she couldn’t have Onnen, she would have her sister.

“I could make a sword for you, too. You shall be Branwen.”

“I don’t want a sword. I want Onnen. I want Hereswith.”

He sighed and stood. “We’ll go now. If you’re frightened.”

She frowned. She wasn’t frightened. She was three; she had her own shoes. Then she heard firm, tidy footsteps on the woodcutters’ path, and she laughed. “Onnen!”

But even as Cian’s mother came into view, Hild frowned again. Onnen was not hurrying. Indeed, Onnen took a moment to smooth her hair, and at that Hild and Cian stepped close together.

Onnen stopped before Hild.

“Your father is dead.”

Hild looked at Cian. He would know what this meant.

“The prince is dead?” he said.

Onnen looked from one to the other. “You’ll not be wanting to call him prince now.”

Far away a settling jackdaw cawed once.

“Da is prince! He is!”

“He was.” With a strong thumb, Onnen wiped a smear of dirt from Hild’s cheekbone. “Little prickle, the lord Hereric was our prince, indeed. But he’ll not be back. And your troubles are just begun.”

Troubles. Hild knew of troubles from songs.

“We go to your lady mother—keep a quiet mouth and a bright mind, I know you’re able. And Cian, bide by me. The highfolk won’t need us in their business just now.”

Cian swished at an imaginary foe. “Highfolk,” he said, in the same tone he said Feed the pigs! when Onnen told him to, but he also rubbed the furrow under his nose with his knuckle, as he did when he was trying not to cry.

Hild put her arms around him. They didn’t quite meet, but she squeezed as hard as she could. Trouble meant they had to listen, not fight.

And then they were wrapped about by Onnen’s arms, Onnen’s cloak, Onnen’s smell, wool and woman and toasted malt, and Hild knew she’d been brewing beer, and the afternoon was almost ordinary again.

“Us,” Cian said, and hugged Hild hard. “We are us.”

“We are us,” Hild repeated, though she wasn’t sure what he meant.

Cian nodded. He kept a protective arm around Hild but looked at his mother. “Was it a wound?”

“It was not, but the rest we’ll chew on later, as we may. For now we get the bairn to her mam and stay away from the hall.”

* * *

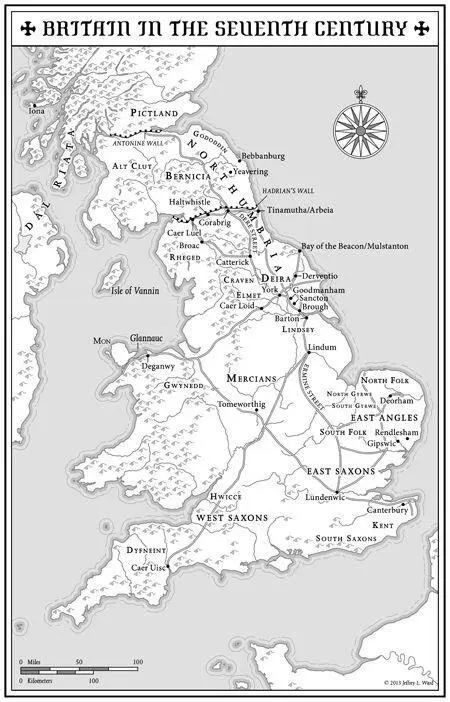

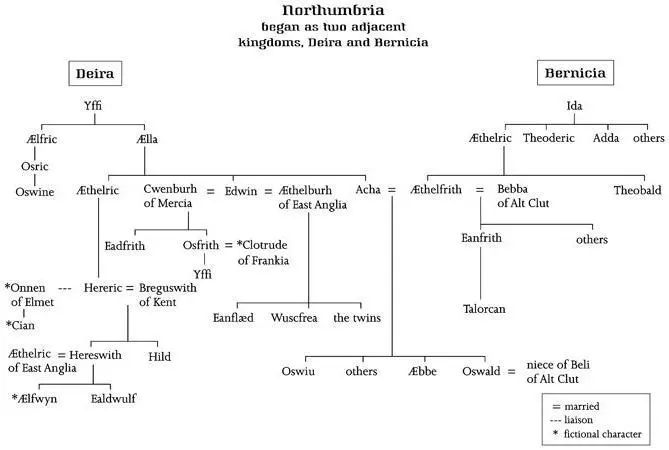

Caer Loid, at the heart of Elmet, wasn’t much of a hall. Hild knew this because when they’d first arrived in the rain months ago, her mother had sniffed her sniff-that-was-a-sigh. Breguswith had done that often in their exile among the kingdoms of the wealh, always as a prelude to driving Onnen and her other women to organise the temporary stop into a reflection of home while she set out her cases of whorls and spindles and tucked her distaff in her belt. At these times, Hild and Hereswith must creep like mice, and the score of sworn warrior gesiths who remained would get more magnificent baldrics for their swords, gold thread in the tablet weave at cuff and hem, even embroidered work along the sleeves. They must look proud and bright and well provided for, that all would know who they were, where they came from, and to where they might still ascend in service of the lady Breguswith and Hereric, her lord, should-be king of Deira.

Hild recalled no sights or sounds of Deira, the standard against which all was compared, the long-left home. She had vague memories of sun on plums, others of a high place of lowing cattle and bitter wind, of ships and wagons and the crook of her father’s arm as he rode, but she knew none of them were home, could be home. Æthelfrith Iding, Anglisc king of Bernicia, had driven them out before she and her sister were born. She recognised people who might be from that long-lost home when they galloped in on foundering horses or slipped through the enclosure fence during the dark of the moon. She knew them by their thick woven cloaks, their hanging hair and beards, and their Anglisc voices: words drumming like apples spilt over wooden boards, round, rich, stirring. Like her father’s words, and her mother’s, and her sister’s. Utterly unlike Onnen’s otter-swift British or the dark liquid gleam of Irish. Hild spoke each to each. Apples to apples, otter to otter, gleam to gleam, though only when her mother wasn’t there. Never stoop to wealh speech, her mother said, not even British, not even with Onnen. Never trust wealh, especially those shaved priestly spies.

* * *

From the byre came the rolling whicker-whinny of horses getting to know each other. At least two new voices. Hild clutched harder at Onnen’s hand and Onnen shook her slightly: Quiet mouth, bright mind!

The riders, two men, were with Ceredig king and the lady Breguswith in the hall. The room was smoky and hot, like all British dwellings—the peat in the great central pit was burning high, though it was not yet cold outside—but still the smell of travel, of horse, was clearly on the men, and their bright, checked cloaks were much muddied at hem and seat. Breguswith, distaff tucked under her left arm, rolling her fine-yarn spindle down her thigh with her right, stared absently at the fire, though Hild knew even as her mother’s fingers were busy, busy, busy teasing out the yarn, testing its tension, her attention was focused on Ceredig king, who laughed and leaned from his stool and let firelight wink on the thick torc around his neck.

Читать дальше