‘You sound surprised,’ he said. ‘I haven’t got the day wrong, have I?’

‘No, of course not, come in.’

The porch was exactly as he remembered it: a jumble of muddy boots, umbrellas, mackintoshes. A powerful smell of wet dog hung over everything, though it was a while before a springer spaniel appeared, his claws clicking on the stone flags: old, milky-eyed, but still going through the motions of defending his mistress and his home.

Paul knelt down and rubbed behind the dog’s ears, producing grunts of contentment. ‘Hello, boy.’

‘Oh, he’ll take any amount of that.’

‘I don’t remember him.’

‘He’d have been in the kitchen; he used to live there more or less. Nowadays, he’s got the run of the house.’ She led the way into the hall. ‘I expect you’d like to freshen up before tea?’

He followed her upstairs, watching the sway of her hips under the narrow skirt, hearing the whisper of silk as her thighs brushed together. Suddenly, he was aroused, impatient to hold her. He’d have liked to reach out now, but knew he had to be careful. She seemed so … friable, as if one rough movement might break her. He’d never seen her like this before.

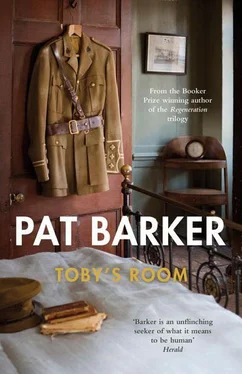

‘I’ve put you in Toby’s room.’

She opened the door and stood aside to let him pass. He swung his kitbag on to the nearest chair. When he looked round she was standing by the bed, stroking the jade-green counterpane. He heard the click of silk threads as they snagged on the palms of her hands.

‘I’m afraid I’m not very well organized these days.’ She didn’t meet his eyes, wouldn’t look at him, kept chafing her arms as if she were cold. ‘I paint till my head spins and then there’s no time left for anything else.’ An attempt at a smile. ‘Anyway. Come down when you’re ready.’

He moved towards her, but she slipped past him.

‘I’ll be in the kitchen. Give me a shout if there’s anything you want.’

I want you .

She’d gone. He heard her footsteps running downstairs.

Left alone, he poured tepid water into a bowl and splashed his face and as much of his neck and chest as he could easily reach. Still dripping, he went to stand in front of the mirror. The face looking back at him had a pink, excited, slightly furtive look. Behind his reflection, he could see one side of the double bed; he didn’t intend to sleep in it alone. The house creaked and sighed all around him. How long had she been living here by herself? Painting, she said, till her head spun, and obviously neglecting herself: she was stick thin. The house, too, seemed bereft. He’d glimpsed dust sheets shrouding the furniture in some of the downstairs rooms. She was not so much living here as camping out, and he felt a stab of pity for her, mingled with curiosity. What on earth possessed her, to shut herself away like this? Of course, her brother’s death must have been devastating, but for a few weeks after it, she’d been seen frequently in town. But then — and nobody seemed to know why — her trips to London had ceased, and she’d walled herself up here, alone.

Well, no doubt she’d tell him, sooner or later. He dried his hands and face and went downstairs.

She was making a cup of tea. ‘I’ve forgotten if you take sugar.’

‘Two, please.’

It mattered, that she’d forgotten. When they first became lovers ‘sugar’ had been their private word for sex. One weekend they’d stayed in a boarding house on the coast — Eastbourne, was it? No, Brighton. Elinor was wearing a wedding ring he’d bought in Woolworth’s. Over tea, sitting in a prim, chintzy lounge on a fat, overstuffed sofa, she’d leaned towards him and said, in a stagey whisper, ‘Darling, I can’t remember, do you take sugar in your tea?’

They’d collapsed in giggles while, at the next table, a middle-aged couple, puzzled and slightly scandalized, had pretended not to listen.

He sat at the kitchen table, his bad leg stretched out in front of him, and watched her pour boiling water into the teapot.

‘How is it? Your leg.’

‘Still attached. I’m one of the lucky ones.’

‘Do you feel lucky?’

‘We-ell. No; yes, I do really.’

‘I’ll let you put the milk in, you know how you like it.’

‘Do you remember the night I proposed to you, I couldn’t kneel down?’

‘I don’t recall you trying very hard.’

‘Oh, I’m sure I did, I was very romantic. Then.’

‘Well, go on, what about it?’

‘It’s the same knee.’

‘That’s it, is it? I was expecting another proposal, at least.’

‘It’s interesting, that’s all. Wounded twice in exactly the same place.’

‘What do you think God’s trying to tell you, Paul? Leave the Church of England? Become a Methodist? They don’t kneel.’

She came and sat opposite him. With her thin arms crossed over her chest, she seemed wary, almost nervous. There was something dried up about her, old-maidish, even. A flare of hope he’d experienced upstairs, when he watched her stroke the counterpane, faded. He thought, sadly, of the house in Ypres where the brass bedstead had seemed to grow till it filled the whole room. And that night, the first night they’d ever spent together, that bed had been the whole world.

‘I kept expecting to see you in London,’ he said.

‘I don’t get up to town much these days.’

He glanced round the room. It was a farmhouse kitchen, designed to be lived in rather than set apart for cooking. A fire burnt in the small grate; there was a scent of pine cones. On a table by the door, a vase of dried hogweed cast dramatic shadows across the whitewashed wall.

‘It’s nice here, but doesn’t it get a bit lonely?’

‘Not really. And I certainly don’t miss London. You get so much more work done down here.’

‘So you are managing to work?’

‘Non-stop. How about you?’

He hesitated. ‘I’ve been commissioned as a war artist.’

‘Yes, I heard.’

He waited for her to congratulate him.

‘Pay’s good. Five pounds a week.’

‘That is good. Have you started anything yet?’

‘I’ve done a couple of landscapes. Well, you know me, what else would I paint?’

‘Corpses?’

‘Not allowed.’

‘Ah.’

‘You don’t approve.’

‘It’s got nothing to do with me.’

The conversation was sticky, punctuated by long silences, though not from any lack of things to say. They were tiptoeing round each other, each aware of the possibility of a sudden flare-up. If nothing else was left of their long, fractious love affair, a willingness to speak hurtful truths, and a fear of hearing them, remained.

‘I’m actually working at the Slade,’ Paul said. ‘I bumped into Tonks and he said I could have a room.’

‘Doesn’t five pounds a week run to a studio?’

‘Yes, but I need a lot of space. Some of the paintings are going to be quite big.’

‘How big?’

He spread his arms wide.

‘Hmm. Mind you don’t fall off the scaffold.’

He laughed, but he was nettled by her sarcasm. This was exactly the kind of prickly, competitive exchange he was used to having with Kit Neville, and one or two other of his male contemporaries. But then, Elinor had always been more like a brilliant, egotistical boy than a girl. He remembered a fancy-dress party at the Slade — the end of his first term — coming into the hall and seeing a figure dressed as Harlequin, wearing a mask. He hadn’t known, at first glance, whether it was a man or a woman. Later, when he danced with her, her body against his had felt slim and muscular, but very far from masculine. The mask, the anonymity, had excited him, especially when he realized there was a second Harlequin figure, also female. He didn’t know, to this day, which girl he’d danced with first.

Читать дальше