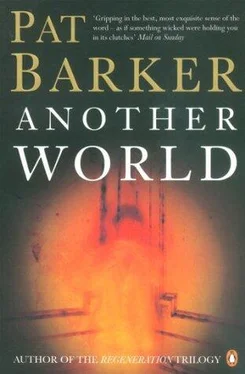

Pat Barker was born in Thornaby-on-Tees in 1943. She was educated at the London School of Economics and has been a teacher of history and politics. Her books include Union Street (1982), winner of the 1983 Fawcett Prize, which has been filmed as Stanley and Iris; Blow Your House Down (1984); Liza’s England (1986), formerly The Century’s Daughter, The Man Who Wasn’t There (1989); the highly acclaimed Regeneration trilogy, comprising Regeneration, The Eye in the Door , winner of the 1993 Guardian Fiction Prize, and The Ghost Road , winner of the 1995 Booker Prize for Fiction; Another World ; and her latest novel, Border Crossing . A single-volume edition of the Regeneration trilogy is also available in Penguin.

Pat Barker is married and lives in Durham.

For David, Donna and Gillon

— with love

Remember: the past won’t fit into memory without something left over; it must have a future.

— JOSEPH BRODSKY

Cars queue bumper to bumper, edge forward, stop, edge forward again. Resting his bare arm along the open window, Nick drums his fingers. The Bigg Market on a Friday night. Litter of chip cartons, crushed lager cans, a gang of lads with stubble heads and tattooed arms looking for trouble — and this is early, it hasn’t got going yet. Two girls stroll past, one wearing a thin, almost transparent white cotton dress. At every stride her nipples show, dark circles beneath the cloth, fish rising. One of the lads calls her name: ‘Julie!’ She turns, and the two of them fall into each other’s arms.

Nick watches, pretending not to.

What is love’s highest aim?Four buttocks on a stem.

Can’t remember who said that — some poor sod made cynical by thwarted lust. Nothing wrong with the aim, as far as Nick can see — just doesn’t seem much hope of achieving it any more. And neither will these two, or not yet. The boy’s mates crowd round, grab him by the belt, haul him off her. ‘Jackie-no-balls,’ the other girl jeers. The boy thrusts his pelvis forward, makes wanking movements with his fist.

Lights still red. Oh, come on. He’s going to be late, and he doesn’t want to leave Miranda waiting at the station. This is her first visit to the new house. Fran wanted to put it off, but then Barbara went into hospital and that settled it. Miranda had to come, and probably for the whole summer. Well, he was pleased, anyway.

The lights change, only to change back to red just as he reaches the crossing. Should be easier in the new house — more space. In the flat Gareth’s constant sniping at Miranda was starting to get on everybody’s nerves. And Miranda never hit back, which always made him want to strangle Gareth, and then it was shouts, tears, banged doors: ‘You’re not my father…’ So who was? he wanted to ask. Never did, of course.

Green — thank God. But now there’s a gang of lads crossing, snarled round two little buggers who’ve chosen this moment to start a fight. His fist hits the horn. When that doesn’t work he leans out of the window, yells, ‘Fuck off out of it, will you?’

No response. He revs the engine, lets the car slide forward till it’s just nudging the backs of their thighs. Shaved heads swivel towards him. Barely time to get the window up before the whole pack closes in, hands with whitening fingertips pressed against the glass, banging on the bonnet, a glimpse of a furred yellow tongue, spit trapped in bubbles between bared teeth, noses squashed against the glass. Then, like a blanket of flies, they lift off him, not one by one, all at the same time, drifting across the road, indifferent now, too good-tempered, too sober to want to bother with him. One lad lingers, spoiling for a fight. ‘Leave it, Trev,’ Nick hears. ‘Stupid old fart int worth it.’

He twists round, sees a line of honking cars, yells, ‘Not my fucking fault!’ then, realizing they can’t hear him, jabs two fingers in the air. Turns to face the front. Jesus, the lights are back to red.

By the time he reaches the station he’s twenty minutes late. Leaving the car in the short-stay car-park, he runs to the platform, only to find it deserted. He stands, staring down the curve of closed doors, while a fear he knows to be irrational begins to nibble at his belly. A few months ago a fourteen-year-old girl was thrown from a train by some yob who hadn’t got anywhere when he tried to chat her up. Miranda’s thirteen. This is all rubbish, he knows that. But then, like everybody else, he lives in the shadow of monstrosities. Peter Sutcliffe’s bearded face, the number plate of a house in Cromwell Street, three figures smudged on a video surveillance screen, an older boy taking a toddler by the hand while his companion strides ahead, eager for the atrocity to come.

Think. Hot day, long journey, she’ll fancy a coke, but when he looks into the café he can’t see her. The place is crowded, disgruntled bundles sipping orange tea from thick cups, shifting suitcases grudgingly aside as he edges between the tables. A smell of hot bodies, bloom of sweat on pale skins, like the sheen on rotten meat, God what a place. And then he sees her, where he should have known all along she would be, waiting sensibly beneath the clock, her legs longer and thinner than he remembers, shoulders hunched to hide the budding breasts. She looks awkward, gawky, Miranda who’s never awkward, whose every movement is poised and controlled. He wants to rush up and kiss her, but stops himself, knowing this is a moment he’ll remember as long as he’s capable of remembering anything.

Then she catches sight of him, her face is transformed, for a few seconds she looks like the old Miranda. Only her kiss isn’t the boisterous hug of even two months ago, but a grown-up peck delivered across the divide of her consciously hollowed chest.

Feeling ridiculously hurt, he picks up her suitcase, puts his other arm around her shoulder, and leads her to the car.

Fran becomes aware that Gareth has come into the room behind her. He moves quietly, and his eyes wince behind his glasses, no more than an exaggerated blink, but it tweaks her nerves, says: You’re a lousy mother. Perhaps I am, she thinks. She’s failed, at any rate, in what seems to be a woman’s chief duty to her son: to equip him with a father who’s more than a bipedal sperm bank. Of course she has supplied Nick, but he’s bugger-all use. Fantastic with other people’s problem kids, bloody useless with his own.

Back to the shopping list. Bran flakes, bumf, toothpaste, toothbrush in case Miranda’s forgotten hers, air freshener, vinegar, potatoes… Something else. What the hell was it?

Gareth blinks again, breathing audibly through his mouth.

She’s tired of the guilt, fed up to the back teeth with attributing every nervous tic, every piece of bad behaviour, every failed exam to the one crucial omission. Nobody knows. Suppose it wasn’t the absence of a father, suppose it was the presence of two mothers? God knows her mother would sink anybody. And the alternative — which it suited everybody to forget — was the North Sea or the incinerator or whatever the bloody hell they did. And he’d come within a hair’s breadth — literally — of that. Lying on the bed, already shaved, when she decided she couldn’t go through with it. She started to cry, the gynaecologist hugged her — and later sent her a bill for 150 quid. Must’ve been the most expensive hug in history. And then she got up, walked down the long gleaming corridor, and out into the open air. She stood outside the phone box for half an hour, a cold wind blowing up her fanny, before plucking up the courage to ring Mark at work. Put on hold for five minutes, she fed ten pees she couldn’t afford into the box, and listened to the theme song from Dr Zhivago . When Mark finally came on the line, he said, ‘I knew you wouldn’t go through with it.’ Typical. Mark had to be in control, had to know what other people were going to do before they did. Later, in bed, he said, ‘Fran, there’s no need to worry. I’ll marry you. I said I would and I will.’ ‘You needn’t,’ she said, pressing her hand over the place where the baby was. And he didn’t. Gone before the hair grew back.

Читать дальше