They sit at the kitchen table together. Nick forces himself to take a bite and washes it down with hot sweet tea. They eat in silence. When she’s finished she wets her forefinger and reflectively picks up crumbs of bread.

‘This is it, isn’t it?’ she says.

‘Yes, he can’t survive that.’

By ‘that’ Nick means not the haemorrhage so much as the humiliating weakness, the exposure. Geordie’s a self-contained man in many ways, fastidious, particular about fingernails and underwear. Nick feels he’s never known him, not because they’ve been distant from each other — far from it — but because they’ve been too close. It’s like seeing somebody an inch away, so that if you were asked to describe them you could probably manage to recall nothing more distinctive than the size of the pores in their nose. Only now, when the proximity of death’s starting to make him recede a little, can Nick make meaningful statements about him: that he’s fanatically clean, that he minds about the state of his fingernails.

After they finish the sandwiches he goes upstairs, but Geordie’s asleep or, at any rate, has his eyes closed. Nick bends over him, trying to check from the movement of his chest that he’s still breathing. Immediately the blue eyes flicker open and he’s subjected to a bright ironical gaze that knows exactly what he’s doing and why.

‘Not yet.’

The doctor arrives mid-morning, Dr Liddle, a middle-aged man with a vaguely clerical demeanour, Scottish accent, repaired hare lip.

Nick runs upstairs ahead of him and tries to lift Grandad into a better position, but he seems to be hardly conscious, his lips move in protest, his eyes remain closed. Nick doesn’t know whether he’s getting worse by the minute or whether he’s simply decided to close his consciousness against this medical invasion. Not that this is particularly invasive. Liddle raises his eyebrows at the sample, takes Geordie’s temperature, his blood pressure, listens to his chest, feels his pulse, looks at the swollen stomach. ‘I’m not going to mess him about prodding his tummy, I can see all I need to see.’

Geordie opens his eyes at last, perhaps objecting to being spoken about in the third person. ‘It’s bleeding again, isn’t it?’ he says, pressing his hands to the old scar.

‘Ye-es, but you’ve got good healing flesh,’ Liddle says comfortably. ‘I don’t think it’ll bleed again.’

No attempt to grapple with the real cause of the haemorrhage. They humour him, all of them, but perhaps that’s what he wants. Perhaps in his own way he’s humouring them. There’s something here Nick can’t grasp. Grandad’s not a man of much formal education, certainly when forced to refer to bodily functions it’s all front passage, back passage stuff, but he’s not stupid. His belief that he’s dying of this ancient wound may be strange, but it isn’t meaningless. The bleeding bayonet wound’s the physical equivalent of the eruption of memory that makes his nights dreadful.

‘You’ll feel a bit weak for a couple of days. Take it easy. We’ll soon have you up and about again.’

Geordie seems to find this optimism consoling. He doesn’t believe a word of it, but he likes to feel the proper things are being said, a tried and trusted routine adhered to.

‘How much pain is he in?’ Liddle asks when they’re out of the room.

Nick and Frieda look at each other. ‘Surprisingly little,’ Nick says.

‘I’m inclined to leave him at home,’ Liddle says. ‘As long as you think you can manage.’

Frieda says, ‘We can manage.’

‘How long do you think he’s got?’ Nick asks.

‘Not long. Days rather than weeks.’

After seeing Liddle out, they go back upstairs and stand at the foot of the bed, looking at Geordie.

‘That went off all right,’ he says, dismissing Liddle, glad to be alone again.

Frieda tidies round, straightening the sheets. Geordie’s tolerant now, letting himself be tidied up, though he rules out shaving, he’s too tired at the moment. He’ll tackle shaving later. Then he leans back against the pillow, his eyes drooping, but not closed. Nick realizes he’s watching shadows dance on the counterpane, leaves with a blue tit pecking about in them, searching for tiny insects. He’s lying like a baby will sometimes lie in its cot, entranced by the play of light and shade.

Frieda’s searching through Geordie’s bureau for his insurance policies.

‘Have you found any?’ Nick asks.

‘Not yet, but they’ll be here somewhere. Here, look at this.’ She holds up a bundle of receipts. ‘He kept everything. Mind you, he was right. They can come back at you.’

‘Not after seven years.’

By the time he’s washed up and tidied the kitchen she’s found the policies, and sits in the armchair, clutching them, looking breathless, excited and slightly guilty. ‘I know you might think this is terrible, with the poor old soul still alive, but you’ve got to be practical,’ she says, turning pink.

‘I don’t think it’s terrible at all.’

But she’s not comfortable. Every remark about the funeral, who should be told, what Grandad’s said he wants done, has to be prefaced by copious disclaimers about not being morbid, grasping, premature, etc. ‘He went in for that thing, you know, that scheme where you sort of freeze the cost of the funeral at what it would’ve been if you’d died at the time you sign on. No matter how long you live it stays the same price.’

‘They’ll be losing money on him.’

‘No, they won’t. He’s not been in it that long.’

Grandad calls down to them. He’s woken up after a long sleep, and Frieda puts the bundle of policies to one side and goes up to attend to him.

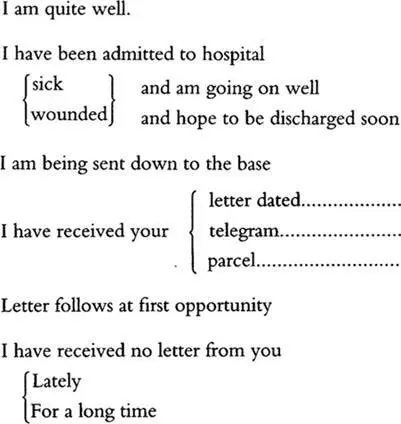

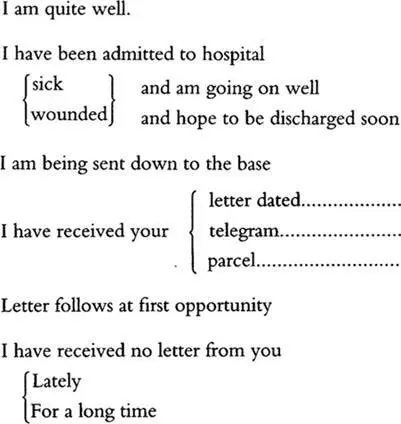

While she’s gone Nick opens a small drawer in the centre of the bureau, where Grandad keeps family snap-shots, a few letters, his birth and marriage certificates, and his field service postcards. All his letters from France have vanished over the years, but these, for some unaccountable reason, have survived. NOTHINGis to be written on this side except the date and signature of the sender. Sentences not required may be erased. If anything else is added the postcard will be destroyed .

After this encouragement to economy of expression, the list of choices.

What fascinates Nick is that word ‘quite’. Does it mean ‘fairly’ or ‘absolutely’? In neither sense can it have been an accurate description of the state of the men who, in the immediate aftermath of battle, sat down, stubby pencils in hand, and crossed out the least appropriate choices.

On 2 July, ten days after Harry’s death, Geordie was ‘quite well’. He was neither sick nor wounded, he had not been admitted to hospital or sent down to base, and he had received a letter from his mother dated the 27th of June.

There are five postcards from then till the end of 1916. In each of them Geordie has crossed out ‘Lately’ so the final message on each card reads: ‘I have received no letter from you for a long time.’

On 14 April 1917, three days after he’d been bayoneted, he’s been admitted to hospital (wounded) and ‘am going on well’ (he nearly died). The address on the other side of the card has been written by somebody else, but the signature, though shaky, is his own. On that occasion too he had not heard from his mother for a long time.

It’s almost as if his mother stopped writing to him after Harry’s death, or at least wrote very rarely. Perhaps she was so shattered she found it difficult to write to anyone, but a son? And in the front line?

Читать дальше