Milburg Mansfield - Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Milburg Mansfield - Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, Путешествия и география, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With Bologna as its central station, the ancient Via Æmilia, begun by the Consul Marcus Æmilius Lepidus, continues towards Cisalpine Gaul the Via Flamina leading out from Rome. It is a delightfully varied itinerary that one covers in following up this old Roman road from Placentia (Piacenza) to Ariminum (Rimini), and should indeed be followed leisurely from end to end if one would experience something of the spirit of olden times, which one can hardly do if travelling by schedule and stopping only at the places lettered large on the maps.

The following are the ancient and modern place-names on this itinerary:

Placentia (Piacenza)

Florentia (Firenzuola)

Fidentia (Borgo S. Donnino)

Parma (Parma)

Tannetum (Taneto)

Regium Lepidi (Reggio)

Mutina (Modena)

Forum Gallorum (near Castel Franco)

Bononia (Bologna)

Claterna (Quaderna)

Forum Cornelii (Imola)

Faventia (Faenza)

Forum Livii (Forli)

Forum Populii (Forlimpopoli)

Caesena (Cesena)

Ad Confluentes (near Savignamo)

Ariminum (Rimini)

Connecting with the Via Æmilia another important Roman road ran from the valley of the Casentino across the Apennines to Piacenza. It was the route traced by a part of the itinerary of Dante in the “Divina Commedia,” and as such it is a historic highway with which the least sentimentally inclined might be glad to make acquaintance.

Another itinerary, perhaps better known to the automobilist, is that which follows the Ligurian coast from Nice to Spezia, continuing thence to Rome by the Via Aurelia. This coast road of Liguria passed through Nice to Luna on the Gulf of Spezia, the towns en route being as follows: —

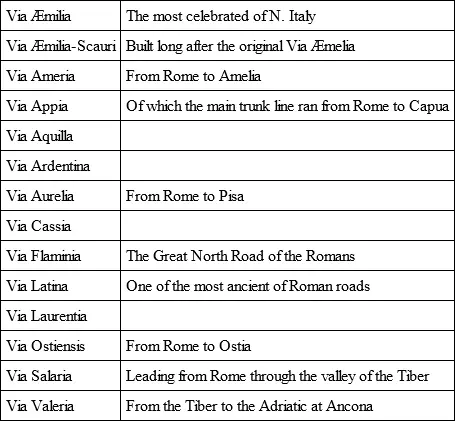

The chief of these great Roman roadways of old whose itineraries can be traced to-day are:

These ancient Roman roads were at their best in Campania and Etruria. Campania was traversed by the Appian Way, the greatest highway of the Romans, though indeed its original construction by Appius Claudius only extended to Capua. The great highroads proceeding from Rome crossed Etruria almost to the full extent; the Via Aurelia, from Rome to Pisa and Luna; the Via Cassia and the Via Clodia.

The great Roman roads were marked with division stones or bornes every thousand paces, practically a kilometre and a half, a little more than our own mile. These mile-stones of Roman times, many of which are still above ground ( milliarii lapides ), were sometimes round and sometimes square, and were entirely bare of capitals, being mere stone posts usually standing on a squared base of a somewhat larger area.

A graven inscription bore in Latin the name of the Consul or Emperor under whom each stone was set up and a numerical indication as well.

Caius Gracchus, away back in the second century before Christ, was the inventor of these aids to travel. The automobilist appreciates the development of this accessory next to good roads themselves, and if he stops to think a minute he will see that the old Romans were the inventors of many things which he fondly thinks are modern.

The automobilist in Italy has, it will be inferred, cause to regret the absence of the fine roads of France once and again, and he will regret it whenever he wallows into a six inch deep rut and finds himself not able to pull up or out, whilst the drivers of ten yoke ox-teams, drawing a block of Carrara marble as big as a house, call down the imprecations of all the saints in the calendar on his head. It’s not the automobilist’s fault, such an occurrence, nor the ox-driver’s either; but for fifty kilometres after leaving Spezia, and until Lucca and Livorno are reached, this is what may happen every half hour, and you have no recourse except to accept the situation with fortitude and revile the administration for allowing a roadway to wear down to such a state, or for not providing a parallel thoroughfare so as to divide the different classes of traffic. There is no such disgracefully used and kept highway in Europe as this stretch between Spezia and Lucca, and one must of necessity pass over it going from Genoa to Pisa unless he strikes inland through the mountainous country just beyond Spezia, by the Strada di Reggio for a détour of a hundred kilometres or more, coming back to the sea level road at Lucca.

Throughout the peninsula the inland roads are better as to surface than those by the coast, though by no means are they more attractive to the tourist by road. This is best exemplified by a comparison of the inland and shore roads, each of them more or less direct, between Florence and Rome.

The great Strada di grande Communicazione from Florence to Rome (something less than three hundred kilometres all told, a mere mouthful for a modern automobile) runs straight through the heart of old Siena, entering the city by the Porta Camollia and leaving by the Porta Romana, two kilometres of treacherous, narrow thoroughfare, though readily enough traced because it is in a bee-line. The details are here given as being typical of what the automobilist may expect to find in the smaller Italian cities. There are, in Italy, none of those unexpected right-angle turns that one comes upon so often in French towns, at least not so many of them, and there are no cork-screw thoroughfares though many have the “rainbow curve,” to borrow Mark Twain’s expression.

On through Chiusi, Orvieto and Viterbo runs the highroad direct to the gates of Rome, for the most part a fair road, but rising and falling from one level to another in trying fashion to one who would set a steady pace.

It is with respect to the grades on Italian roads, too, that one remarks a falling off from French standards. North of Florence, in the valley of the Mugello, we, having left the well-worn roads in search of something out of the common, found a bit of seventeen per cent. grade. This was negotiated readily enough, since it was of brief extent, but another rise of twenty-five per cent. (it looked forty-five from the cushions of a low-hung car) followed and on this we could do nothing. Fortunately there was a way around, as there usually is in Europe, so nothing was lost but time, and we benefited by the acquisition of some knowledge concerning various things which we did not before possess. And we were content, for that was what we came for anyway.

From Florence south, by the less direct road via Arezzo, Perugia and Terni, there is another surprisingly sudden rise but likewise brief. It is on this same road that one remarks from a great distance the towers of Spoleto piercing the sky at a seemingly enormous height, while the background mountain road over the Passo della Somma rises six hundred and thirty metres and tries the courage of every automobilist passing this way.

To achieve many of these Italian hill-towns one does not often rise abruptly but rather almost imperceptibly, but here, in ten kilometres, say half a dozen miles, the Strada di grande Communicazione rises a thousand feet, and that is considerable for a road supposedly laid out by military strategists.

As a contrast to these hilly, switch-back roads running inland from the north to the south may be compared that running from Rome to Naples, not the route usually followed via Vallombrosa and Frosinone, but that via Velletri, Terracina and Gaeta. Here the highroad is nearly flat, though truth to tell of none too good surface, all the way to Naples. Practically it is as good a road as that which runs inland and offers to any who choose to pass that way certain delights that most other travellers in Italy know not of.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Italian Highways and Byways from a Motor Car» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.