James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, История, foreign_edu, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

In recent years we have come to realize that matter is not the manifold material we were accustomed to think it when we accepted the hypothesis that there were some seventy odd different kinds of atoms, each one absolutely independent of any other and representing an ultimate term in science. The atomic theory from this standpoint has proved to be only a working hypothesis that was useful for a time, but that our physicists are now agreed must not be considered as something absolute. Radium has been observed changing into helium and the relations of atoms to one another as they are now known, make it almost certain that all of them have an underlying sub-stratum the same in all, but differentiated by the dynamic energies with which matter in its different forms is gifted. Sir Oliver Lodge has stated this theory of the constitution of matter very clearly in recent years, and in doing so has only been voicing the practically universal sentiment of those who have been following the latest developments in the physical sciences. Strange as it may appear, this was exactly the teaching of Aquinas and the schoolmen with regard to the constitution of matter. They said that the two constituting principles of matter were prime matter and form. By prime matter they meant the material sub-stratum the same in all material things. By form they meant the special dynamic energy which, entering into prime matter, causes it to act differently from other kinds and gives it all the particular qualities by which we recognize it. This theory was not original with them, having been adopted from Aristotle, but it was very clearly set forth, profoundly discussed, and amply illustrated by the schoolmen. In its development this theory was made to be of the greatest help in the explanation of many other difficulties with regard to living as well as non-living things in their hands. The theory has its difficulties, but they are less than those of any other theory of the constitution of matter, and it has been accepted by more philosophic thinkers since the Thirteenth Century than any other doctrine of similar nature. It may be said that it was reached only by deduction and not by experimental observation. Such an expression, however, instead of being really an objection is rather a demonstration of the fact that great truths may be reached by deduction yet only demonstrated by inductive methods many centuries later.

Of course it may well be said even after all these communities of interest between the medieval and the modern teaching of the general principles of science has been pointed out, that the universities of the Middle Ages did not present the subjects under discussion in a practical way, and their teaching was not likely to lead to directly beneficial results in applied science. It might well he responded to this, that it is not the function of a university to teach applications of science but only the great principles, the broad generalizations that underlie scientific thinking, leaving details to be filled in in whatever form of practical work the man may take up. Very few of those, however, who talk about the purely speculative character of medieval teaching have manifestly ever made it their business to know anything about the actual facts of old-time university teaching by definite knowledge, but have rather allowed themselves to be guided by speculation and by inadequate second-hand authorities, whose dicta they have never taken the trouble to substantiate by a glance at contemporary authorities on medieval matters.

It will be interesting to quote for the information of such men, the opinion of the greatest of medieval scientists with regard to the reason why men do not obtain real knowledge more rapidly than would seem ought to be the case, from the amount of work which they have devoted to obtaining it. Roger Bacon, summing up for Pope Clement the body of doctrine that he was teaching at the University of Oxford in the Thirteenth Century, starts out with the principle that there are four grounds of human ignorance. "These are first, trust in inadequate authority; second, the force of custom which leads men to accept too unquestioningly what has been accepted before their time; third, the placing of confidence in the opinion of the inexperienced; and fourth, the hiding of one's own ignorance with the parade of a superficial wisdom." Surely no one will ever be able to improve on these four grounds for human ignorance, and they continue to be as important in the twentieth century as they were in the Thirteenth. They could only have emanated from an eminently practical mind, accustomed to test by observation and by careful searching of authorities, every proposition that came to him. Professor Henry Morley, Professor of English Literature at University College, London, says of these grounds for ignorance of Roger Bacon, in his English Writers, Volume III, page 321: "No part of that ground has yet been cut away from beneath the feet of students, although six centuries ago the Oxford friar clearly pointed out its character. We still make sheep walks of second, third, and fourth and fiftieth-hand references to authority; still we are the slaves of habit; still we are found following too frequently the untaught crowd; still we flinch from the righteous and wholesome phrase, 'I do not know'; and acquiesce actively in the opinion of others that we know what we appear to know. Substitute honest research, original and independent thought, strict truth in the comparison of only what we really know with what is really known by others, and the strong redoubt of ignorance has fallen."

The number of things which Roger Bacon succeeded in discovering by the application of the principle of testing everything by personal observation, is almost incredible to a modern student of science and of education who has known nothing before of the progress in science made by this wonderful man. He has been sometimes declared to be the discoverer of gunpowder, but this is a mistake since it was known many years before by the Arabs and by them introduced into Europe. He did study explosives very deeply, however, and besides learning many things about them realized how much might be accomplished by their use in the after-time. He declares in his Opus Magnum: "That one may cause to burst forth from bronze, thunderbolts more formidable than those produced by nature. A small quantity of prepared matter occasions a terrible explosion accompanied by a brilliant light. One may multiply this phenomenon so far as to destroy a city or an army." Considering how little was known about gunpowder at this time, this was of itself a marvelous anticipation of what might be accomplished by it.

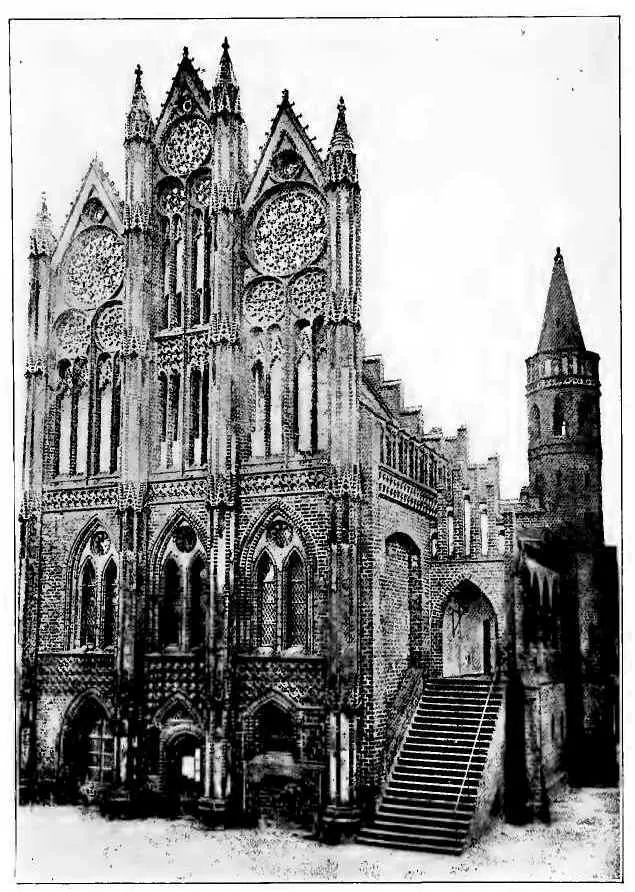

RATHHAUS (TANGERMÜNDE)

Bacon prophesied, however, much more than merely destructive effects from the use of high explosives, and indeed it is almost amusing to see how closely he anticipated some of the most modern usages of high explosives for motor purposes. He seems to have concluded that some time the apparently uncontrollable forces of explosion would come under the control of man and be harnessed by him for his own purposes. He realized that one of the great applications of such a force would be for transportation. Accordingly he said: "Art can construct instruments of navigation such that the largest vessels governed by a single man will traverse rivers and seas more rapidly than if they were filled with oarsmen. One may also make carriages which without the aid of any animal will run with remarkable swiftness." 5 5 These quotations are taken from Ozanam's Dante and Catholic Philosophy, published by the Cathedral Library Association, New York, 1897.

When we recall that the very latest thing in transportation are motor-boats and automobiles driven by gasoline, a high explosive, Roger Bacon's prophesy becomes one of these weird anticipations of human progress which seem almost more than human.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.