James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James Walsh - The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, История, foreign_edu, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

JACQUES COEUR'S HOUSE (BOURGES)

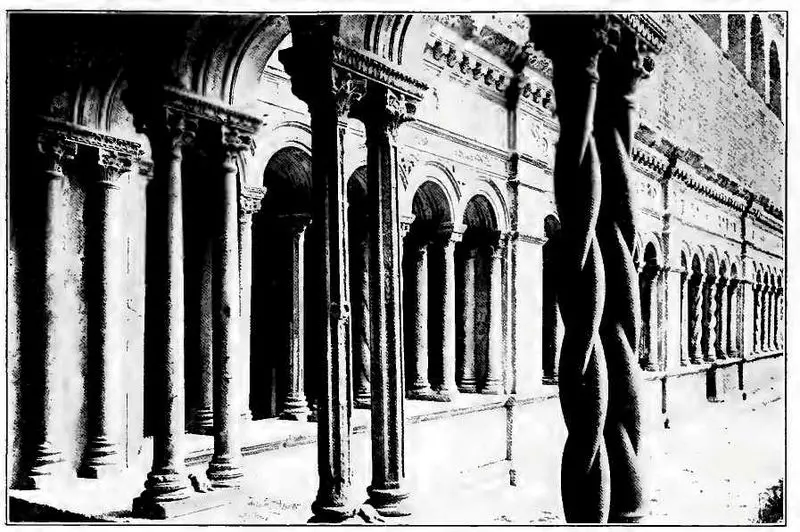

CLOISTER OF ST. JOHN LATERAN (ROME)

III

WHAT AND HOW THEY STUDIED AT THE UNIVERSITIES

It is usually the custom for text books of education to dismiss the teaching at the universities of the Middle Ages with some such expression as: "The teachers were mainly engaged in metaphysical speculations and the students were occupied with exercises in logic and in dialectics, learning in long drawn out disputations how to use the intellectual instruments they possessed but never actually applying them. All knowledge was supposed to be amenable to increase through dialectical discussion and all truth was supposed, to be obtainable as the conclusion of a regular syllogism." Great fun especially is made of the long-winded disputations, the time-taking public exercises in dialectics, the fine hair-drawn distinctions presumably with but the scantiest basis of truth behind them and in general the placing of words for realities in the investigation of truth and the conveyance of information. The sublime ignorance of educators who talk thus about the century that saw the rise of the universities in connection with the erection of the great Cathedrals, is only equaled by their assumption of knowledge.

It is very easy to make fun of a past generation and often rather difficult to enter into and appreciate its spirit. Ridicule comes natural to human nature, alas! but sympathy requires serious mental application for understanding's sake. Fortunately there has come in recent years a very different feeling in the minds of many mature and faithful students of this period, as regards the Middle Ages and its education. Dialectics may seem to be a waste of time to those who consider the training of the human mind as of little value in comparison with the stocking of it with information. Dialectical training will probably not often enable men to earn more money than might have otherwise been the case. This will be eminently true if the dialectician is to devote himself to commercial enterprises in his future life. If he is to take up one of the professions, however, there may be some doubt as to whether even his practical effectiveness will not be increased by a good course of logic. There is, however, another point of view from which this matter of the study of dialectics may be viewed, and which has been taken very well by Prof. Saintsbury of the University of Edinburgh in a recent volume on the Thirteenth Century.

He insists in a passage which we quote at length in the chapter on the Prose of the Century, that if this training in logic had not been obtained at this time in European development, the results might have been serious for our modern languages and modern education. He says: "If at the outset of the career of the modern languages, men had thought with the looseness of modern thought, had indulged in the haphazard slovenliness of modern logic, had popularized theology and vulgarized rhetoric, as we have seen both popularized and vulgarized since, we should indeed have been in evil case." He maintains that "the far-reaching educative influence in mere language, in mere system of arrangement and expression, must be considered as one of the great benefits of Scholasticism." This is, after all, only a similar opinion to that evidently entertained by Mr. John Stuart Mill, who, as Prof. Saintsbury says, was not often a scholastically-minded philosopher, for he quotes in the preface of his logic two very striking opinions from very different sources, the Scotch philosopher, Hamilton, and the French philosophical writer, Condorcet. Hamilton said, "It is to the schoolmen that the vulgar languages are indebted for what precision and analytical subtlety they possess." Condorcet went even further than this, and used expressions that doubless will be a great source of surprise to those who do not realize how much of admiration is always engendered in those who really study the schoolmen seriously and do not take opinions of them from the chance reading of a few scattered passages, or depend for the data of their judgment on some second-hand authority, who thought it clever to abuse these old-time thinkers. Condorcet thought them far in advance of the old Greek philosophers for, he said, "Logic, ethics, and metaphysics itself, owe to scholasticism a precision unknown to the ancients themselves."

With regard to the methods and contents of the teaching in the undergraduate department of the university, that is, in what we would now call the arts department, there is naturally no little interest at the present time. Besides the standards set up and the tests required can scarcely fail to attract attention. Professor Turner, in his History of Philosophy, has summed up much of what we know in this matter in a paragraph so full of information that we quote it in order to give our readers the best possible idea in a compendious form of these details of the old-time education.

"By statutes issued at various times during the Thirteenth Century it was provided that the professor should read, that is expound, the text of certain standard authors in philosophy and theology. In a document published by Denifle, (the distinguished authority on medieval universities) and by him referred to the year 1232, we find the following works among those prescribed for the Faculty of Arts: Logica Vetus (the old Boethian text of a portion of the Organon, probably accompanied by Porphyry's Isagoge); Logica Nova (the new translation of the Organon); Gilbert's Liber Sex Principorium; and Donatus's Barbarismus. A few years later (1255), the following works are prescribed: Aristotle's Physics, Metaphysics, De Anima, De Animalibus, De Caelo et Mundo, Meteorica, the minor psychological treatises and some Arabian or Jewish works, such as the Liber de Causis and De Differentia Spirititus et Animae."

"The first degree for which the student of arts presented himself was that of bachelor. The candidate for this degree, after a preliminary test called responsiones (this regulation went into effect not later than 1275), presented himself for the determination which was a public defense of a certain number of theses against opponents chosen from the audience. At the end of the disputation, the defender summed up, or determined, his conclusions. After determining, the bachelor resumed his studies for the licentiate, assuming also the task of cursorily explaining to junior students some portion of the Organon. The test for the degree of licentiate consisted in a collatio , or exposition of several texts, after the manner of the masters. The student was now a licensed teacher; he did not, however, become magister, or master of arts, until he had delivered what was called the inceptio , or inaugural lecture, and was actually installed ( birrettatio ). If he continued to teach he was called magisier actu regens ; if he departed from the university or took up other work, he was called magister non regens . It may be said that, as a general rule, the course of reading was: (1) for the bachelor's degree, grammar, logic, and psychology; (2) for the licentiate, natural philosophy; (3) for the master's degree, ethics, and the completion of the course of natural philosophy."

Quite apart from the value of its methods, however, scholasticism in certain of its features had a value in the material which it discussed and developed that modern generations only too frequently fail to realize. With regard to this the same distinguished authority whom we quoted with regard to dialectics, Prof. Saintsbury, does not hesitate to use expressions which will seem little short of rankly heretical to those who swear by modern science, and yet may serve to inject some eminently suggestive ideas into a sadly misunderstood subject.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Thirteenth, Greatest of Centuries» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.