James White - The Eighteen Christian Centuries

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «James White - The Eighteen Christian Centuries» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, История, foreign_edu, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Eighteen Christian Centuries

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Eighteen Christian Centuries: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Eighteen Christian Centuries»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Eighteen Christian Centuries — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Eighteen Christian Centuries», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

If these were the habits of the rich, how were the poor treated? The free and penniless citizens of the capital were degraded and gratified at the same time. The wealthy vied with each other in buying the favour of the mob by shows and other entertainments, by gifts of money and donations of food. But when these arts failed, and popularity could no longer be obtained by merely defraying the expense of a combat of gladiators, the descendants of the old patricians—of the men who had bought the land on which the Gauls were encamped outside the gates of Rome—went down into the arena themselves and fought for the public entertainment. Laws indeed were passed even in the reign of Tiberius, and renewed at intervals after that time, against this shameful degradation, and the stage was interdicted to all who were not previously declared infamous by sentence of a court. But all was in vain. Ladies of the highest rank, and the loftiest-born of the nobility, actually petitioned for a decree of defamation, that they might give themselves up undisturbed to their favourite amusement. This perhaps added a zest to their enjoyment, and rapturous applauses must have hailed the entrance of the beautiful grandchild of Anthony or Agrippa, in the character and drapery of a warlike amazon—the louder the applause and greater the admiration. Yet in order to gratify them with such a sight, she had descended to the level of the convict, and received the brand of qualifying disgrace from a legal tribunal. But the faint barrier of this useless prohibition was thrown down by the policy and example of Domitian. The emperor himself appeared in the arena, and all restraint was at an end. Rather, there was a fury of emulation to copy so great a model, and “Rome’s proud dames, whose garments swept the ground,” forgot more than ever their rank and sex, and were proud, like their lovers and brothers, not merely to mount the stage in the lascivious costume of nymph or dryad, but to descend into the blood-stained lists of the Coliseum and murder each other with sword and spear. There is something strangely horrible in this transaction, when we read that it occurred for the first time in celebration of the games of Flora—the goddess of flowers and gardens, who, in old times, was worshipped under the blossomed apple-trees in the little orchards surrounding each cottage within the walls, and was propitiated with children’s games and chaplets hung upon the boughs. But now the loveliest of the noble daughters of the city lay dead upon the trampled sand. What was the effect upon the populace of these extraordinary shows?

Always stern and cruel, the Roman was now never satisfied unless with the spectacle of death. Sometimes in the midst of a play or pantomime the fierce lust of blood would seize him, and he would cry out for a combat of gladiators or nobles, who instantly obeyed; and after the fight was over, and the corpses removed, the play would go on as if nothing had occurred. The banners of the empire still continued to bear the initial letters of the great words—the Senate and people of Rome. We have now, in this rapid survey, seen what both those great names have come to—the Senate crawling at the feet of the emperor, and the people living on charity and shows. The slaves fared worst of all, for they were despised by rich and poor. The sated voluptuary whose property they were sometimes found an excitement to his jaded spirits by having them tortured in his sight. They were allowed to die of starvation when they grew old, unless they were turned to use, as was done by one of their possessors, Vidius Pollio, who cast the fattest of his domestics into his fish-pond to feed his lampreys. The only other classes were the actors and musicians, the dwarfs and the philosophers. They contributed by their wit, or their uncouth shape, or their oracular sentences, to the amusement of their employers, and were safe. They were licensed characters, and could say what they chose, protected by the long-drawn countenance of the stoic, or the comic grimaces of the buffoon. So early as the time of Nero, the people he tyrannized and flattered were not less ruthless than himself. In his cruelty—in his vanity—in his frivolity, and his entire devotion to the gratification of his passions—he was a true representative of the men over whom he ruled. Emperor and subject had even then become fitted for each other, and flowers, we are credibly told by the historians, were hung for many years upon his tomb.

Humanity itself seemed to be sunk beyond the possibility of restoration; but we see now how necessary it was that our nature should reach its lowest point of depression to give full force to the great reaction which Christianity introduced. Men were slavishly bending at the footstool of a despot, trembling for life, bowed down by fear and misery, when suddenly it was reported that a great teacher had appeared for a while upon earth, and declared that all men were equal in the sight of God, for that God was the Father of all. The slave heard this in the intervals of his torture—the captive in his dungeon—the widow and the orphan. To the poor the gospel, or good news, was preached. It was this which made the trembling courtiers of the worst of the emperors slip out noiselessly from the palace, and hear from Paul of Tarsus or his disciples the new prospect that was opening on mankind. It spread quickly among those oppressed and hopeless multitudes. The subjection of the Roman empire—its misery and degradation—were only a means to an end. The harsher the laws of the tyrant, the more gracious seemed the words of Christ. The two masters were plainly set before them, which to choose. And who could hesitate? One said, “Tremble! suffer! die!” The other said, “Come unto me, all ye that are weary and heavy laden, and I will give you rest!”

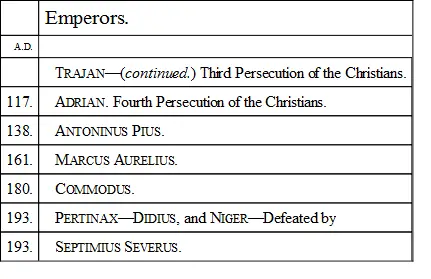

SECOND CENTURY

Pliny the Younger, Plutarch, Suetonius, Juvenal, Arrian, Ælian, Ptolemy, (Geographer,) Appian, Epictetus, Pausanias, Galen, (Physician,) Athenæus, Tertullian, Justin Martyr, Tatian, Irenæus, Athenagoras, Theophilus of Antioch, Clement Of Alexandria, Marcion, (Heretic.)

THE SECOND CENTURY

In looking at the second century, we see a total difference in the expression, though the main features continue unchanged. There is still the central power at Rome, the same dependence everywhere else; but the central power is beneficent and wise. As if tired of the hereditary rule of succession which had ended in such a monster as Domitian, the world took refuge in a new system of appointing its chiefs, and perhaps thought it a recommendation of each successive emperor that he had no relationship to the last. We shall accordingly find that, after this period, the hereditary principle is excluded. It was remarked that, of the twelve first Cæsars, only two had died a natural death—for even in the case of Augustus the arts of the poisoner were suspected—and those two were Vespasian and Titus, men who had no claim to such an elevation in right of lofty birth. Birth, indeed, had ceased to be a recommendation. All the great names of the Republic had been carefully rooted out. Few people were inclined to boast of their ancestry when the proof of their pedigree acted as a sentence of death; for there was no surer passport to destruction in the times of the early emperors than a connection with the Julian line, or descent from a historic family. No one, therefore, took the trouble to inquire into the genealogy of Nerva, the old and generous man who succeeded the monster Domitian. |A.D. 96.|His nomination to the empire elevated him at once out of the sphere of these inquiries, for already the same superstitious reverence surrounded the name of Augustus which spreads its inviolable sanctity on the throne of Eastern monarchs. Whoever sits upon that, by whatever title, or however acquired, is the legitimate and unquestioned king. No rival, therefore, started up to contest the position either of Nerva himself, or of the stranger he nominated to succeed him. |A.D. 102.|Men bent in humble acquiescence when they knew, in the third year of this century, that their master was named Trajan,—that he was a Spaniard by birth, and the best general of Rome. For eighty years after that date the empire had rest. Life and property were comparatively secure, and society flowed on peaceably in deep and well-ascertained channels. A man might have been born at the end of the reign of Domitian, and die in extreme old age under the sway of the last of the Antonines, and never have known of insecurity or oppression—

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Eighteen Christian Centuries»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Eighteen Christian Centuries» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Eighteen Christian Centuries» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.