Robert Walsh - Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Walsh - Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, foreign_home, История, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Around the fountain is the great market, the most busy and populous spot on the peninsula of Pera. It is held between the gate of Galata on one side, and the manufactory of pipes on the other: above is the descent from Pera to the Bosphorus, and below the crowded place of embarkation, so that the confluence of people from these several resorts, creates an almost impassable crowd. Among the articles of sale, the most numerous and conspicuous are usually gourds and melons, of which there are more than twenty kinds, called by the Greek Kolokithia , and by the Turk Cavac . They are piled in large heaps, in their season, to the height of 10 or 15 feet. Some of them are of immense size, of a pure white, and look like enormous snow-balls−they are used for soups: others are long and slender−the pulp is thrust out, and the cavity filled with forced-meat. This is called Dolma , and is so favourite a dish, that a large valley on the Bosphorus is called Dolma Bactche , or the gourd garden, from its cultivation. Another is perfectly spherical, and called Carpoos . It contains a rich red pulp, and a copious and cooling juice, and is eaten raw. A hummal, or porter, may be seen, occasionally, tottering up the streets of Pera, sinking under the weight of an incredible load, and overcome by the heat of a burning sun. His remedy for fatigue is a slice of melon, which refreshes him so effectually, that he is instantly enabled to pursue his toilsome journey. The Turkish mode of carrying planks through their streets is attended with serious inconvenience to passengers. The boards are attached to the sides of a horse in such a manner, extending from side to side of the narrow streets, that they cannot fail of crushing or fracturing the legs of the inexperienced or inactive that happen to meet them. Neither are the dogs, nor their most frequent attitude, forgotten in our illustration. The market-place is their constant resort: there they quarrel for the offals; and a Frank, whose business leads him to that quarter, has reason to congratulate himself, if he shall escape the blow of a plank from the passing horse, or the laceration of his flesh by an irritated dog.

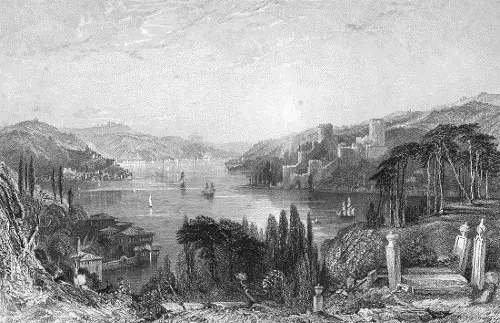

ROUMELI HISSAR, OR, THE CASTLE OF EUROPE.

ON THE BOSPHORUS

T. Allom. R. Smith.

The supposed origin of the Bosphorus is connected with the most awful phenomena of nature; and the lovely strait, which now combines all that is beautiful and romantic, grateful to the eye, and soothing to the mind, owes its existence to all that is fearful and tremendous.−At its eastern extremity, and above the level of the Mediterranean, there existed an inland sea, covering vast plains with a wide expanse of waters, several thousand miles in circumference. By a sudden rupture, it is supposed, an opening was made, through which the waters rushed, and inundated the subjacent countries. For this supposition there are strong foundations of probability. The comparatively small sheets of water now partially occupying the space which the greater sea once covered, under the names of the Euxine, Azoph, Caspian, and Aral seas, are only the deeper pools of this great fountain, which has, in a succession of ages, been drained off, leaving the shallower parts dry land, with all the marks of an alluvial soil. The spot where the great rupture is supposed to have taken place is indicated by volcanic remains: basalt, scoriæ, and other debris of calcination, lying all around. The strait itself bears all the marks of a chasm violently torn open, the projections of one shore corresponding to the indentations of the other, and the similar strata of both being at equal elevations, while the bottom is a succession of descents, over which the water still tumbles with the rapidity of a cataract. The opinions of antiquaries accord with natural appearances. The first land which this mighty inundation encountered was the continent of Greece, over which it swept with irresistible force. Tradition has handed down to us the flood of Deucalion; and ancient writings have assigned as its cause, “the rupture of the Cyanean rocks:” so that both poets and historians concur in preserving the memory of this awful event.

After the first effects of this inundation had ceased, a current was still propelled by the Danube, the Borysthenes, and other great rivers, which pour their copious streams into the Euxine, and have no other outlet: hence it still runs down with considerable velocity. In some places, where the convulsion seems to have left the bottom like steps of stairs, this is dangerously increased. It is possible that the continued attrition of the water, for thousands of years over this rocky surface, has worn it down to a more uniform level; still three cataracts remain, one is called shetan akindisi , or “the devil’s current:” it is necessary, from its laborious ascent, to haul ships up against it with considerable toil. To the ancients it was accounted a perilous navigation, when the broken ledges were still more abrupt. Among the acts of daring intrepidity was deemed the navigation of this strait. Hence Horace says−

“To the mad Bosphorus my bark I’ll guide,

And tempt the terrors of its raging tide.”

There is not a promontory or recess in all its windings, that is not hallowed by the recollection of either fictitious mythology or authentic history. The ancient name of Bosphorus signifies “the traject of the ox;” the passage being so narrow that such animals swam across it, and hence it is sometimes spelled Bosporos. But the fanciful mythology of the Greeks assigned a more poetic derivation of the name. They assert that Iö, having assumed the form of a cow, to escape the vigilance of Juno, in her solitary wanderings swam across this strait, and consigned to fame the tradition of the event by the name it bears. One promontory preserves the name of Jason, who landed there in his bold attempt to explore the unknown recesses of the Euxine. Another retains that of Medea, for there she dispensed her youth-giving drugs, and conferred upon the place that reputation of salubrity which still distinguishes it. The narrow pass, that divided Europe from Asia, was also the transit chosen by great armies. Here Darius crossed, when the hosts of Asia first poured into Europe, and the rage of conquest led the gorgeous monarch of the East, from the luxuries and splendour of his own court, to penetrate into the rude and barbarous haunts of the wandering Scythians. Here it was that Xenophon, and his intrepid handful of Greeks, crossed over, to return to their own country. Here it was that the Christian crusaders embarked their armies, to rescue the holy sepulchre from the infidels; and here it was that the infidels, in return, entered Europe, and destroyed the mighty Christian empire of the East.

The accompanying illustration exhibits the scene of these events, and so commemorates the deeds of remote and recent ages. The strait is here not more than seven stadia, or furlongs, across; and, as Pliny truly says, “You can hear in one orb of the earth, the dogs bark and the birds sing in the other; and may hold conversation from shore to shore when the sound is not dispersed by the wind.” In particular seasons, during the migration of fish, boats are seen, extending in a continued line, and forming a bridge from side to side. The rock on which Darius sat is still pointed out; and, if a stranger occupy the rude seat at such a moment, it will powerfully recall to his imagination those times when mighty armies crossed and recrossed on a similar fragile footing.

The events connected with Roumeli Hissar, or the Castle of Europe, are of surpassing interest. When the fierce Mahomet determined to extinguish the feeble Roman empire, and transfer the Moslem capital to a Christian soil, he found two dilapidated towers, one in Asia, and the other in Europe, which had been suffered to fall into utter decay. He re-edified that on the Asiatic shore, and, having been allowed to do this without opposition, crossed over and rebuilt the European castle also, so as completely to command the navigation of the straits, by occupying two forts on the most prominent points of the nearest parts of it. When the emperor remonstrated against this violation of his territory, he was tauntingly but fiercely answered, that “since the Greeks were not able to protect their own possessions, he would do it for them;” and he threatened to slay alive the next person who came to remonstrate. To establish his usurped right, he prohibited the navigation of the strait by foreigners. The Venetians refused to comply with this arbitrary mandate, and attempted to pass; but their vessel was struck by a ball from one of those enormous cannon which Mahomet had caused to be cast for the destruction of the Greek empire: the crew were beheaded, and their bodies hung out of the castle, to deter others from similar attempts. The castle was thence called Chocsecen , “the amputator of heads;” and such is the immutability of Turkish ferocity, that, with reason, it retains the name at this day.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.