Robert Vane Russell - The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Robert Vane Russell - The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_prose, История, foreign_edu, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

11. Superstitions

They have various spells to cure a man possessed of an evil spirit, or stung by a snake or scorpion, or likely to be in danger from tigers or wild bears; and in the Morsi tāluk of Berār it is stated that they so greatly fear the effect of an enemy writing their name on a piece of paper and tying it to a sweeper’s broom that the threat to do this can be used with great effect by their creditors. 129 129 Kitts, l.c.

To drive out the evil eye they make a small human image of powdered turmeric and throw it into boiled water, mentioning as they do so the names of any persons whom they suspect of having cast the evil eye upon them. Then the pot of water is taken out at midnight of a Wednesday or a Sunday and placed upside down on some cross-roads with a shoe over it, and the sufferer should be cured. Their belief about the sun and moon is that an old woman had two sons who were invited by the gods to dinner. Before they left she said to them that as they were going out there would be no one to cook, so they must remember to bring back something for her. The elder brother forgot what his mother had said and took nothing away with him; but the younger remembered her and brought back something from the feast. So when they came back the old woman cursed the elder brother and said that as he had forgotten her he should be the sun and scorch and dry up all vegetation with his beams; but the younger brother should be the moon and make the world cool and pleasant at night. The story is so puerile that it is only worth reproduction as a specimen of the level of a Mahār’s intelligence. The belief in evil spirits appears to be on the decline, as a result of education and accumulated experience. Mr. C. Brown states that in Malkāpur of Berār the Mahārs say that there are no wandering spirits in the hills by night of such a nature that people need fear them. There are only tiny pari or fairies, small creatures in human form, but with the power of changing their appearance, who do no harm to any one.

12. Social rules

When an outsider is to be received into the community all the hair on his face is shaved, being wetted with the urine of a boy belonging to the group to which he seeks admission. Mahārs will eat all kinds of food including the flesh of crocodiles and rats, but some of them abstain from beef. There is nothing peculiar in their dress except that the men wear a black woollen thread round their necks. 130 130 Ibidem .

The women may be recognised by their bold carriage, the absence of nose-rings and the large irregular dabs of vermilion on the forehead. Mahār women do not, as a rule, wear the choli or breast-cloth. An unmarried girl does not put on vermilion nor draw her cloth over her head. Women must be tattooed with dots on the face, representations of scorpions, flowers and snakes on the arms and legs, and some dots to represent flies on the hands. It is the custom for a girl’s father or mother or father-in-law to have her tattooed in one place on the hand or arm immediately on her marriage. Then when girls are sitting together they will show this mark and say, ‘My mother or father-in-law had this done,’ as the case may be. Afterwards if a woman so desires she gets herself tattooed on her other limbs. If an unmarried girl or widow becomes with child by a man of the Mahār caste or any higher one she is subjected after delivery to a semblance of the purification by fire known as Agnikāsht. She is taken to the bank of a river and there five stalks of juāri are placed round her and burnt. Having fasted all day, at night she gives a feast to the caste-men and eats with them. If she offends with a man of lower caste she is finally expelled. Temporary exclusion from caste is imposed for taking food or drink from the hands of a Māng or Chamār or for being imprisoned in jail, or on a Mahār man if he lives with a woman of any higher caste; the penalty being the shaving of a man’s face or cutting off a lock of a woman’s hair, together with a feast to the caste. In the last case it is said that the man is not readmitted until he has put the woman away. If a man touches a dead dog, cat, pony or donkey, he has to be shaved and give a feast to the caste. And if a dog or cat dies in his house, or a litter of puppies or kittens is born, the house is considered to be defiled; all the earthen pots must be thrown away, the whole house washed and cleaned and a caste feast given. The most solemn oath of a Mahār is by a cat or dog and in Yeotmāl by a black dog. 131 131 Stated by Mr. C. Brown.

In Berār, the same paper states, the pig is the only animal regarded as unclean, and they must on no account touch it. This is probably owing to Muhammadan influence. The worst social sin which a Mahār can commit is to get vermin in a wound, which is known as Deogan or being smitten by God. While the affliction continues he is quite ostracised, no one going to his house or giving him food or water; and when it is cured the Mahārs of ten or twelve surrounding villages assemble and he must give a feast to the whole community. The reason for this calamity being looked upon with such peculiar abhorrence is obscure, but the feeling about it is general among Hindus.

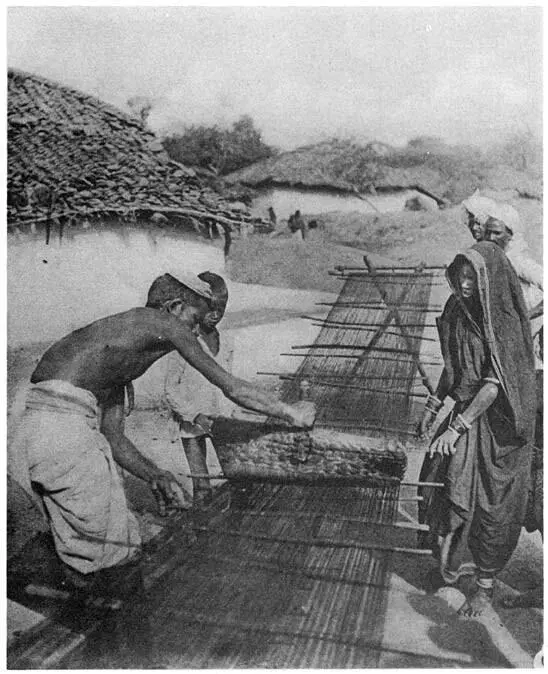

Weaving: sizing the warp

13. Social subjection

The social position of the Mahārs is one of distressing degradation. Their touch is considered to defile and they live in a quarter by themselves outside the village. They usually have a separate well assigned to them from which to draw water, and if the village has only one well the Mahārs and Hindus take water from different sides of it. Mahār boys were not until recently allowed to attend school with Hindu boys, and when they could not be refused admission to Government schools, they were allotted a small corner of the veranda and separately taught. When Dher boys were first received into the Chānda High School a mutiny took place and the school was boycotted for some time. The people say, ‘ Mahār sarva jātīcha bāhar ’ or ‘The Mahār is outside all castes.’ Having a bad name, they are also given unwarrantably a bad character; and ‘ Mahār jātīchā ’ is a phrase used for a man with no moral or kindly feelings. But in theory at least, as conforming to Hinduism, they were supposed to be better than Muhammadans and other unbelievers, as shown by the following story from the Rāsmāla: 132 132 Vol. ii. p. 237.

A Muhammadan sovereign asked his Hindu minister which was the lowest caste. The minister begged for leisure to consider his reply and, having obtained it, went to where the Dhedas lived and said to them: “You have given offence to the Pādishāh. It is his intention to deprive you of caste and make you Muhammadans.” The Dhedas, in the greatest terror, pushed off in a body to the sovereign’s palace, and standing at a respectful distance shouted at the top of their lungs: “If we’ve offended your majesty, punish us in some other way than that. Beat us, fine us, hang us if you like, but don’t make us Muhammadans.” The Pādishāh smiled, and turning to his minister who sat by him affecting to hear nothing, said, ‘So the lowest caste is that to which I belong.’ But of course this cannot be said to represent the general view of the position of Muhammadans in Hindu eyes; they, like the English, are regarded as distinguished foreigners, who, if they consented to be proselytised, would probably in time become Brāhmans or at least Rājpūts. A repartee of a Mahār to a Brāhman abusing him is: The Brāhman, ‘ Jāre Mahārya ’ or ‘Avaunt, ye Mahār’; the Mahār, ‘ Kona dīushi neīn tumchi goburya ’ or ‘Some day I shall carry cowdung cakes for you (at his funeral)’; as in the Marātha Districts the Mahār is commonly engaged for carrying fuel to the funeral pyre. Under native rule the Mahār was subjected to painful degradations. He might not spit on the ground lest a Hindu should be polluted by touching it with his foot, but had to hang an earthen pot round his neck to hold his spittle. 133 133 Bombay Gazetteer , vol. xii. p. 175.

He was made to drag a thorny branch with him to brush out his footsteps, and when a Brahman came by had to lie at a distance on his face lest his shadow might fall on the Brāhman. In Gujarāt 134 134 Rev. A. Taylor in Bombay Gazetteer, Gujarāt Hindus , p. 341 f.

they were not allowed to tuck up the loin-cloth but had to trail it along the ground. Even quite recently in Bombay a Mahār was not allowed to talk loudly in the street while a well-to-do Brāhman or his wife was dining in one of the houses. In the reign of Sidhrāj, the great Solanki Rāja of Gujarāt, the Dheras were for a time at any rate freed from such disabilities by the sacrifice of one of their number. 135 135 The following passage is taken from Forbes, Rāsmāla , i. p. 112.

The great tank at Anhilvāda Pātan in Gujarāt had been built by the Ods (navvies), but Sidhrāj desired Jusma Odni, one of their wives, and sought to possess her. But the Ods fled with her and when he pursued her she plunged a dagger into her stomach, cursing Sidhrāj and saying that his tank should never hold water. The Rāja, returning to Anhilvada, found the tank dry, and asked his minister what should be done that water might remain in the tank. The Pardhān, after consulting the astrologers, said that if a man’s life were sacrificed the curse might be removed. At that time the Dhers or outcastes were compelled to live at a distance from the towns; they wore untwisted cotton round their heads and a stag’s horn as a mark hanging from their waists so that people might be able to avoid touching them. The Rāja commanded that a Dher named Māyo should be beheaded in the tank that water might remain. Māyo died, singing the praises of Vishnu, and the water after that began to remain in the tank. At the time of his death Māyo had begged as a reward for his sacrifice that the Dhers should not in future be compelled to live at a distance from the towns nor wear a distinctive dress. The Rāja assented and these privileges were afterwards permitted to the Dhers for the sake of Māyo.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Tribes and Castes of the Central Provinces of India, Volume 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.