In this way the hunters had gunned down polar bears on the icebergs of Alaska, practically exterminated the Javan rhinoceroses, and massacred the gentle, dreamy orangutans of Borneo. Sometimes they went off on pigsticking parties in Spain, running wild boars through with spears as they quietly snuffled under the chestnut trees, or they would fly to some African lake and mow down hundreds of gorgeous flamingos from the comfort of their jeeps.

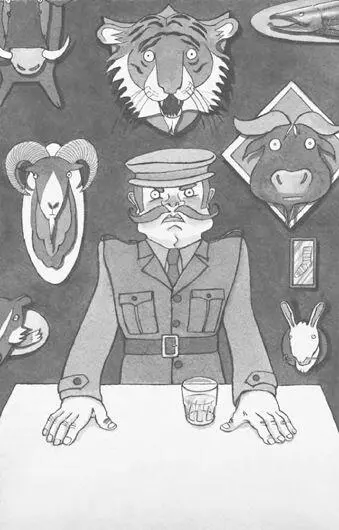

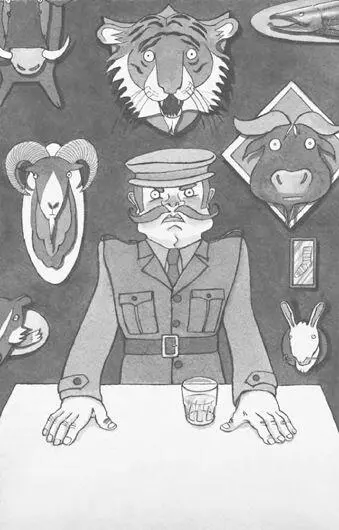

“Now then, gentlemen,” said the club president, a man called Colonel Bagwackerly, who had a boiled-looking face, pop eyes, and a sticky mustache that clung like a slice of ginger pudding to his face. “As you know, we are here to discuss a very important matter.”

“A very important matter!” yelled the hunters, banging their glasses on the table. They were already rather drunk.

“As you know,” Bagwackerly went on, “next week our great club is going to be one hundred years old.”

“One hundred years old!” repeated the hunters, hiccuping and slapping each other on the back.

“And we are here to decide what kind of hunt we should have for our anniversary celebrations.”

“A big hunt! The biggest hunt ever!” cried the drunken hunters.

“Quite so,” said Bagwackerly. “The only question is, what shall we hunt? And where?”

“How about polishing off the rest of the blue whales?” said a black-bearded Scotsman who called himself the MacDermot-Duff of Huist and Carra and went around in a bloodred kilt and a sporran hung with a dozen dangling badgers’ claws.

But the others shook their heads. Not enough sport, they said, and it was true. So many of these rare and marvelous animals had already been destroyed by greedy whale hunters that you could travel a thousand miles across the ice-blue waters of the Antarctic and not sight one.

“Vat if ve go schtickpigging?” said a German member, Herr Blutenstein from Hamburg. But the others shook their heads again. For a big centenary hunt they wanted something bigger than pigsticking: something with guns in it, and explosions, and blood.

One member suggested a kangaroo shoot in Australia, but so many of the kangaroos had already been turned into steaks that that wasn’t any good. Someone else suggested the wild camels in the Andes, but a revolution was going on somewhere in South America and the hunters liked shooting things, not getting shot.

And then a small man with gold-rimmed spectacles and a pinched, pale nose got to his feet.

“I know!” he squeaked. “I know! I’ve got a great idea!”

“What is it, Prink?” said Colonel Bagwackerly in a weary voice.

They had let Mr. Prink belong to the club because he was a very rich saucepan manufacturer and they needed him to buy helicopters and things like that. But everyone despised him: he was weedy and twittery and had a huge wife, called Myrtle Prink, of whom he was dreadfully afraid.

Now he tried to jump on his chair, fell off, and squeaked: “Yetis! That’s what we should hunt! Abominable Snowmen! Fly out to the Himalayas and have a great big yeti hunt!”

There were groans from the other hunters and the MacDermot-Duff of Huist and Carra swore a dreadful oath. “Don’t be an imbecile, Prink,” he said. “There aren’t any such things.”

“Yes, there are, there are!” shouted Mr. Prink. “Look!”

And he took out a bundle of newspapers and threw them down on the table.

They were the papers that had been printed after Lucy’s footsteps had been found on Nanvi Dar, and the headlines said things like: ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN STALKS AGAIN or MYSTERIOUS DENIZENS OF THE MOUNTAIN HEIGHTS or IT’S YES TO THE YETIS.

“Pull yourself together, Prink,” snarled Bagwackerly. “A pack of newspaper lies.”

“It isn’t; I’m sure it isn’t,” squealed Mr. Prink. “We could stalk them in the snow and flush them from their lairs and shoot them with exploding bullets. We could have a yeti skin for the billiard room and yeti tusks in the armory and—”

“Ein yeti schkalp für die library!” shouted Herr Blutenstein from Hamburg.

“That’s enough !” thundered Colonel Bagwackerly. “If I hear another word about yetis, Prink, I’ll have you thrown out of the club.” He broke off. “Drat it, that’s the doorbell, and I had to send the servants away. Can’t have them prying into our affairs. Go and see who it is, Prink. You might as well do something useful for once.”

So Mr. Prink got up and went out of the room. When he came back, he couldn’t speak. His mouth opened, his mouth shut, but that was all.

“Well, what is it?” said Bagwackerly impatiently. “Who was there?”

“It’s … it’s … what you said I mustn’t say another word about,” stammered Mr. Prink. “With … bedsocks.”

Furiously, Bagwackerly pushed him aside and strode out into the hall. When he came back, his bloated face looked as though it had been dipped in flour. “My God,” he said, groping to loosen his tie, “my God …”

And then, with a great effort, he pulled himself together. “Shut the door, quickly, quickly,” he said. “We’ve only got a couple of minutes. We must make a plan.”

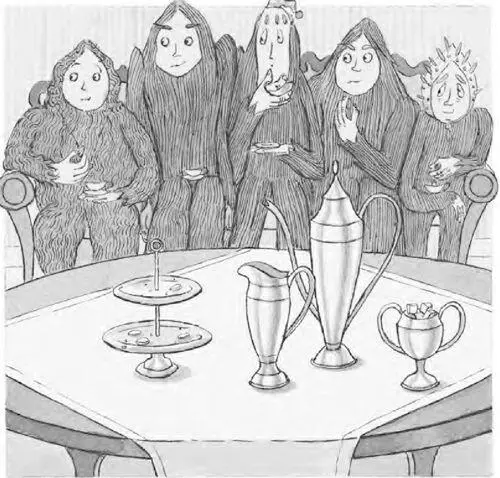

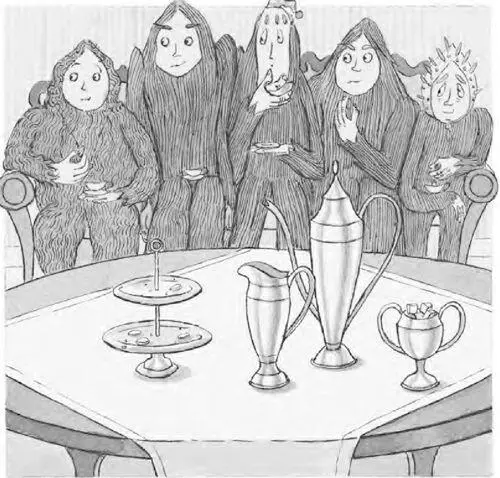

The yetis were sitting in the Blue Salon having afternoon tea. They were sitting very close together though the room was vast — so close that Ambrose and Lucy could curl their eighth toes together like they used to do when they were small.

Polite afternoon tea is not an easy meal for yetis. When they balanced the fragile teacups on their knees, the cups sank right into their fur and couldn’t easily be found again, and the biscuits were so thin that they had to say “Sorry, biscuit” about ten times before they got a mouthful.

But that wasn’t why they were sitting so close together. They were sitting like that because of the things on the walls. Lady Agatha had not told them about the things that would be on the walls of the Blue Salon and the Gold Drawing Room and all the other rooms that the yetis had seen. Right above Ambrose, so that his trunk almost dipped into Ambrose’s teacup, was the head of a poor dead elephant. Grandma was sitting next to a large stuffed marabou and Uncle Otto’s bald patch had two nasty scratches where a pair of moose antlers had caught him as he bent forward to pass the jam.

And though Lady Agatha’s relations had been very nice to them, somehow they had not been quite like the yetis expected. The one with the red face and the gingery mustache who said he was Uncle George had such strange pop eyes, and when he spoke, it made the yetis feel that they were soldiers on parade rather than members of the family. Uncle Mac, who came from Scotland, had sworn quite dreadfully when he had spilled some hot water on his bare and tufty knees, and though the yetis were used to Bad Language from when Perry changed a wheel, somehow this was different. As for Uncle Leslie, he was such a twitchy, squeaky little man that he made the yetis very nervous. There didn’t seem to be any women in the family either, which was a pity. A woman’s touch would perhaps have made them feel more welcome.

“’Ump,” said Clarence sadly. He meant the lump of sugar, which, for the third time, had dropped from the sugar tongs onto the carpet.

“I wish Con and Ellen would come,” whispered Ambrose — and it was rather an uncertain whisper. “They promised to say good-bye to us.”

“Another cup of tea?” asked Uncle George.

But the yetis said thank you, they had had enough.

Читать дальше