There was a long silence while the yetis looked at him.

“ People do that?” said Ambrose at last. “Proper human people?”

Con nodded miserably.

The yetis didn’t say anything. But one by one they went up to their bunks and shut their ear lids and turned their faces to the wall. They wanted to have nothing to do with Santa Maria, not even to see a place where things like that were done.

After crawling along for another few hundred yards, Perry gave up. People had come in from the surrounding countryside to see the fight and had just parked their cars and motorbikes and farm carts anywhere they could, jamming up the roads completely.

“We’ll have to wait till it’s over,” he said, “and people move their stuff.”

So he drew up under a poster, which announced that this very afternoon, Pedro the Passionate, the most famous matador in Spain, was going to fight El Magnifico, the fiercest bull ever to be bred on the ranches of Pamplona. And when Perry had convinced Con that the Mutter -shouting girl was not likely to turn up with her parents six hundred miles from where they’d left her, the boy agreed to join Perry and Ellen at a pavement café, where they had ice cream and watched the streets empty as everyone was drawn, as if by a gigantic magnet, toward the bullring in the central square.

Meanwhile, back in the lorry, Hubert was feeling lonely and neglected. The yetis were still lying on their bunks with their faces to the wall. Nobody loved him. Nobody cared .

His boot face began to crumple. He threw back his head, ready to bleat.

And then he stopped. He had heard a voice. An incredible voice, deep and thrilling and purple. Not a moo. Something stronger than a moo. More of a roar.

Could it be …?

But no, it didn’t sound quite like his mother.

The noise came again. A low, throbbing sort of bellow. And suddenly Hubert knew what it was. Something even more exciting than his mother. Something he’d had long ago and forgotten all about.

The thing that was making that noise — was Hubert’s father !

It took Hubert some time to push up the iron bar that closed the back of the lorry, but butting steadily with his little crumpled horn, he did it. The yetis had dozed off with their ear lids closed. No one noticed Hubert jump down, trot across the deserted square, and reach the edge of the bullring.

It was made of wooden palings, high and solid and unclimbable. But Hubert didn’t mean to climb. Puffing with excitement, he trotted round it looking for a soft place in the ground.

From inside, the bellow came again, filling the whole square with its power.

Hubert hesitated no longer. There was a small gap in the wooden railing patched with canvas, and beside it a pile of rubble where a new water pipe went underground. A perfect Hubert Hole. And putting down his battered head, the little yak began to dig.

The bull they called El Magnifico stood alone in the center of the ring. Sweat gleamed on the huge hump of muscle that ran down his back; his eyes were wide with terror; blood streamed from a wound in his flank.

A few days ago he had roamed free on the range, feeling the wind between his horns, the good grass beneath his feet. Then men had come and carted him away and kept him for two days in a darkened pen. And now he’d been pushed, half-blinded, into this place where men rushed at him on horses and others leaped at him with arrows, and everywhere there were flickering red cloths, and the screams of the crowd, and pain and fear.

But El Magnifico was a great bull. He did not understand why these things were being done to him, but he would fight to the end. And he lowered his head and pawed the ground, and when the prancing men came with their arrows, he charged.

“Olé!” yelled the crowd. And “Aah!” as a banderillero vaulted to safety over the barrier.

But the bull was growing tired. One of the banderillero’s arrows had pierced the muscles of his throat. Soon Pedro the Passionate would provoke him to the charge that would be his last.

“Kill!” roared the crowd to Pedro the Passionate. “Kill the bull! Kill! Kill! Kill!”

Wretched, exhausted, scenting his own death, the great bull lifted his head in a last bellow of misery and pain.

The bellow was answered. Not by an answering roar exactly. By a small but very happy bleat. And then the yak called Hubert tottered on his spindly legs into the ring.

He was covered in sawdust and rubble, his left horn looked like a toy corkscrew, and a piece of water pipe, dislodged by his tunneling, had caught in his tail.

Ignoring the murmurs of the crowd, not even seeing the picadors on their skinny horses or the prancing banderilleros with their arrows or Pedro the Passionate standing openmouthed, his cape in his hand, Hubert tottered forward. Only one thing existed for him: El Magnifico the bull.

“Father!” said Hubert in yak language. “Daddy! It’s your son. It’s me!”

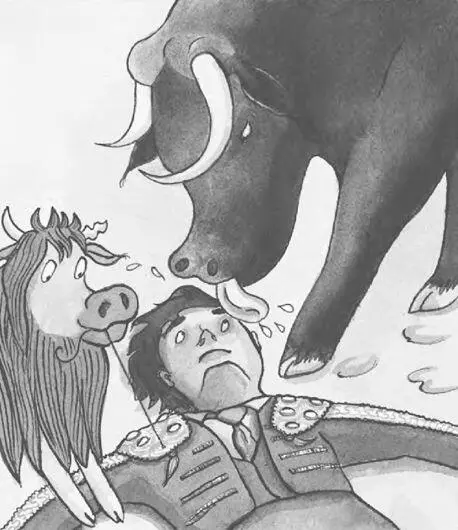

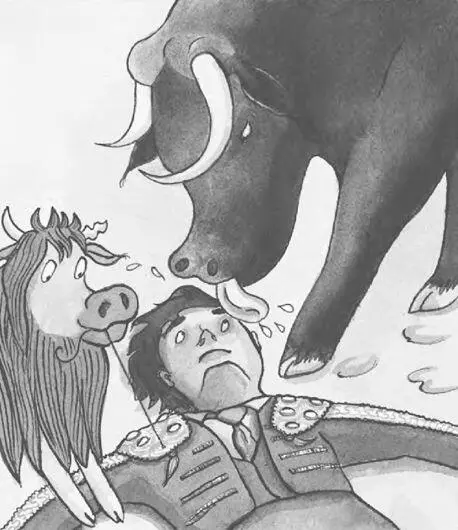

El Magnifico was completely taken by surprise. He stopped bellowing and pawing and charging and bent his head to look at whatever it was that was blissfully butting him from underneath. He didn’t think he had a calf like that. His calves, as far as he remembered, were larger and smoother and had a different smell. But with fifty wives, one could never be sure. And slowly El Magnifico put out his huge, rough tongue and carefully, painstakingly, began to lick Hubert into shape.

Hubert had never been so happy. No one had licked him since he’d left Nanvi Dar. He trembled with joy, he squeaked with pleasure, he rolled over on his back …

“Aah! The sweet little one,” sighed the women in the crowd.

Pedro the Passionate was furious. There are rules about bullfighting like there are rules about boxing. You can’t just go up to the back end of a bull and stick him in the behind. To earn his money, Pedro had to make him charge.

So he flicked his fingers, and the picadors on their poor skinny horses tried to ride up to El Magnifico again and jab him with their spears and make him fight.

But they had reckoned without the horses. A pawing, stamping bull was their enemy — but a father licking his son was a different matter. They, too, had had foals in distant and happy days before they were sold off to be ripped to pieces in the ring. At first they just wouldn’t budge, however much the picadors jabbed them with their spears. And then, to show they meant business — the horses sat down.

After that the audience went mad. The men rolled about in their seats laughing. The women took out their handkerchiefs and began to sob, because it was all so touching and beautiful.

But Pedro the Passionate nearly exploded with rage. He was being turned into a laughingstock. He had to kill the bull. He had to show them.

So angry was he that he felt no fear, but pranced right up to the bull and flicked him with his cape. Anything to make him charge.

El Magnifico didn’t even notice. He was working on a particularly difficult place behind Hubert’s right ear. But Hubert had seen the cape: a nasty, swirling thing it was, and it made him nervous. With a worried bleat he rushed forward — right between Pedro the Passionate’s velvet trouser legs.

And the last bullfight of the season ended with the mightiest matador in Spain lying flat on his back in the sawdust, a pram-sized yak nibbling the bobbles of his embroidered waistcoat — and the fiercest bull ever bred in Pamplona licking them both.

Читать дальше

Читать дальше