“Say ‘Mummy’,” she would yell at him. “Go on, say it. Say ‘Mummy’.”

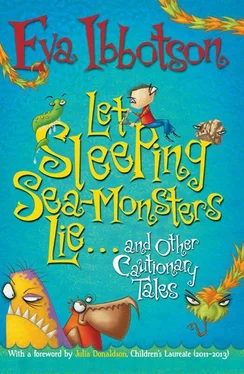

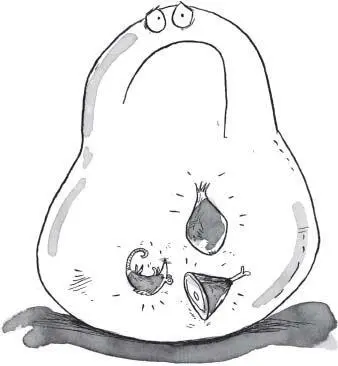

But the Brollachan couldn’t say “Mummy”. He couldn’t say anything. His mouth was big but he used it for eating, not for talking. So he would roll away sadly and suck in a large turnip or a dead rat or a ham-bone and you would see them — the turnip or the rat or the ham-bone — lying inside him sort of glowing a little until they gradually became part of the Brollachan because that is what happens to the things that Brollachans eat.

All day long the Brollachan’s mother followed him about, flapping a wet cloth at the furniture and dripping water on him.

“I don’t know what will become of you, Brollachan. Why aren’t you outside drowning someone? Why are you sitting in that bucket? Why don’t you do something with your life? And why don’t you say ‘Mummy’?”

The Brollachan tried hard to please her. But however wide he opened his mouth, all that came out was a kind of gulp or a sort of glucking noise.

Sometimes the Brollachan’s mother invited her friends round; ladies like Black Annis who was a cannibal witch with a blue face or the Hag of the Dribble who was covered all over in grey slime, and then she would start.

“You don’t know how I worry about him,” she would say to these ladies, prodding the Brollachan with her webbed foot as he lay politely on the floor. “I can’t sleep for worrying about him. He’s so backward; he doesn’t even try to frighten people into fits. And he won’t say ‘Mummy’!”

“You should punish him,” said the cannibal witch, burping rudely because she always swallowed people whole and this gave her wind. “Make him kneel on dried peas — nothing more painful than that!”

Which was not only a cruel but a silly thing to say since the Brollachan did not have any knees.

One day the Brollachan and his mother went for a walk in the forest. The Brollachan liked the forest very much. It was not wet like the swamp where he lived and the leaves felt pleasantly tickly under his body. He stretched himself out more and more and became bush-shaped, then tree-shaped, and then just Brollachan-shaped but extra large. He felt happy and he felt free.

But the Brollachan’s mother was still talking. “Why don’t you learn the names of the trees, Brollachan?” she said. “Why don’t you at least try to give off an evil mist? There’s a Brollachan in the next valley who has a whole village gibbering with fright every time he shows himself. And he can say ‘Mummy’!”

After a while the Brollachan rolled away between the trees and he rolled and he rolled and he rolled until he was quite a way from his mother.

The Brollachan’s mother did not notice this at first because she was so busy talking. “It’s all right for you,” she said. “You can’t have a stomach ache from worrying because you haven’t got a stomach. You can’t have a headache from worrying because you haven’t got a head. You can’t — Brollachan, where are you? Brollachan, come here at once, I’m talking to you. How dare you hide from your mother! I can see your vile red eyes behind that tree. I know you’re just pretending to be that smelly toadstool. Now come to your mummy, Brollachan; come at once!”

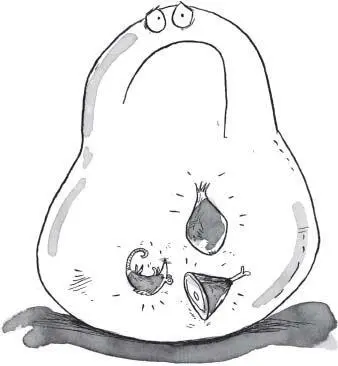

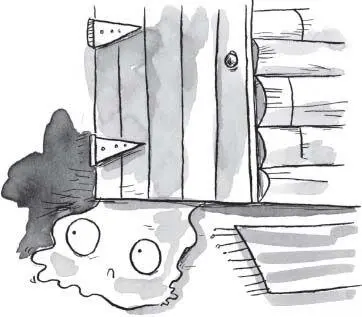

But the Brollachan was a long, long way away and he was well and truly lost. He rolled on, however, until he came to a little wooden house in a clearing and because he was very tired by now, he oozed through the crack under the door and went inside.

It was a very nice house. There was a fire in the grate and a painted stool and a rocking chair in one corner. In the rocking chair, fast asleep, sat an old man with a kind face and a long white beard. Everything was quiet and everything was dry and the Brollachan liked it very much. And becoming more or less the shape of the hearthrug he lay down by the fire, closed his vile red eyes and fell asleep.

He slept for one hour and he slept for two while outside in the forest his mother, the Fuath, roared about on her webbed feet, searching and scolding and calling him. Goodness knows how long he might have gone on sleeping but just then a burning coal fell out of the fireplace and landed on one of the Brollachan’s bulges.

Now the Brollachan couldn’t talk but he could scream — and scream he did!

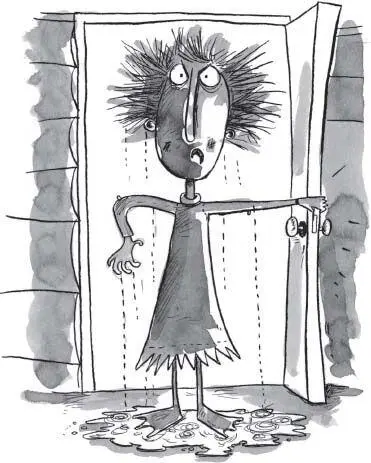

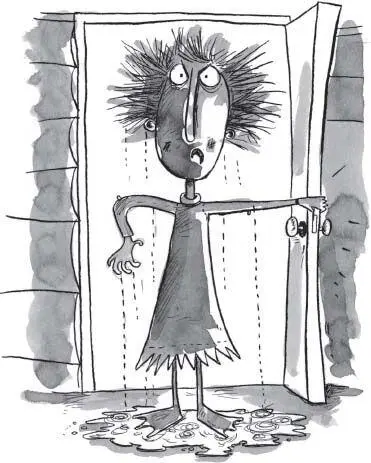

Everything then happened at once. The old man woke, saw that there was a Brollachan on his hearthrug and jumped from his rocking chair. The Brollachan’s mother heard the scream and rushed in at the front door, dripping and shouting as she came.

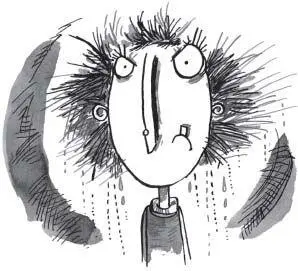

“What’s happened to you, Brollachan? How did you get here? Who hurt you? Has that nasty old man hurt you? Have you hurt my Brollachan, you stupid old man? Because if you have I’ll turn you into a bat with bunions. I’ll turn you into an eel with earache. I’ll claw you into strips of raw beef, I’ll make newts come out of your nostrils, I’ll…”

On and on she raged. The old man did not know how to bear so much noise. He took his long white beard and stuffed the left half of it into his left ear and the right half of it into his right ear but still he could hear the Fuath’s voice. Feeling quite desperate he got a broom and tried to shoo the Fuath out of doors.

But the Fuath would not be shushed and she would not be shooed. She just dripped and she threatened and she talked .

The Brollachan by now was very upset. His burn did not hurt any longer but he felt that things were not as they should be. His red eyes were wide with worry and his shapeless darkness shivered at all this unpleasantness. What he wanted more than anything was to make things all right.

So he made himself very big and he opened his mouth and he went right up to his mother, who was still talking and scolding and waving her arms. If only he could do it! If only he could do the thing she wanted so much! Wider he opened his mouth and wider… and closer he went to his mother and closer… and harder he tried and harder… harder than he had ever tried in his whole life.

And then at last he did it. He actually did it!

“MUMMY!” said the Brollachan. “MUM — gluck — gulp!”

Then he stopped. His mother was not there.

Читать дальше