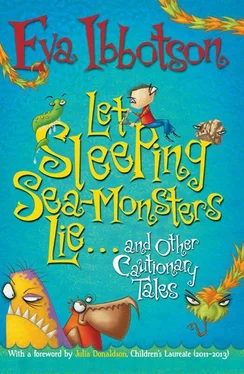

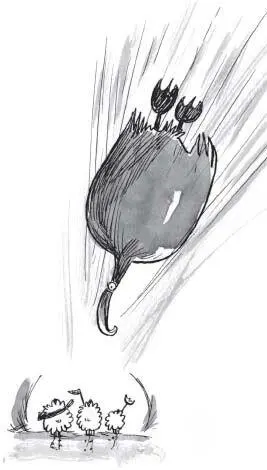

The Boobrie did not smile because birds don’t but she was very pleased. One sheep would have been good, two would have been better but three sheep — one for each of her chicks — was perfect. She circled once and dived down on to the moor.

This was the moment the Scotsmen had been waiting for. They had got it all planned. As the bird came down they were going to step out from under their sheepskins, point their horse pistol and their blunderbuss and their catapult at the soft underbelly of the bird — and fire!

What actually happened was different. As the Boobrie swooped towards MacDuff, the brave Scotsman tried to lift his gun, got the catch wedged against his wooden leg and let loose a rain of bullets into a frozen cow pat. Tall MacGregor managed to get his arm out and shoot off the blunderbuss but though he had filled it from a tin labelled Black Bullets these were not proper bullets but a dark kind of peppermint which has the same name — and if there is one thing you cannot kill a Boobrie with it is a rain of peppermints. As for fat MacCallum, he had fainted clean away before he could loose off his catapult with the brass bedknob which he had brought to fire at the Boobrie’s heart.

The Boobrie, who was a bit short-sighted, did not notice any of these things. All she noticed were three ordinary, though rather wiggly, sheep.

So first she swooped on brave MacDuff and picked him up and flew with him to the nest by the loch and dropped him down in front of Chick Number One. Then she flew back and swooped down on the skinny MacGregor sheep and dropped him down in front of Chick Number Two. And lastly she went back for the MacCallum sheep which was a very quiet sheep because the fat Scotsman was still in a faint.

After this the Boobrie felt very pleased with herself and waited for the chicks to start eating the sheep she had so kindly brought them.

But they didn’t. The chicks looked down with their goofy pop-eyes at the sheep. They bent their scraggy necks. They pecked at the sheep with their yellow beaks and turned them over with their webbed feet. And then they looked reproachfully at their mother.

“Not nice,” said Chick Number One.

“Smells nasty,” said Chick Number Two.

And Chick Number Three, who was the youngest, just said gloomily: “Legs.”

“Hairy,” explained the first chick to its mother. “Hairy legs.”

“And wooden,” said Chick Number Two, picking at the MacDuff sheep.

“Pink faces,” said the youngest chick, who was taking it hard. It turned over the top end of the MacCallum sheep with its beak. “Horrid,” it said, choking a little.

An anxious look spread over the mother Boobrie’s face. She peered down at the nest, turned over MacDuff and lifted the sheepskin off MacCallum who had come out of his faint and was making a lot of noises, none of which were “Baa!”

The chicks were right. These were not proper sheep. A mistake had been made. And when you have made a mistake there is only one thing to do: put it right.

So the mother Boobrie picked up MacDuff in his sheepskin, carried him high in her beak and dropped him with a splash into the loch.

Next she picked up the MacGregor sheep, carried him high and dropped him into the loch.

Then she went back for the MacCallum sheep and dropped him into the loch too.

And then she went flapping away on her enormous wings to go and look for some proper sheep because a mother’s work is never done.

As for the Scotsmen, they managed to swim ashore and to hobble home, one in his underpants, one in his vest to which a frozen frog had stuck, and one in nothing but a large leaf, and for the rest of the year they had chilblains in places it would not be polite to mention. MacDuff’s wooden leg was lost in the water and so were all the rest of their things, which serves them right for trying to trick a Boobrie bird. Boobries may be a little silly, but if you give them time they can always tell a Scotsman from a sheep.

The Brollachan Who Kept Mum

This is a story about a Brollachan.

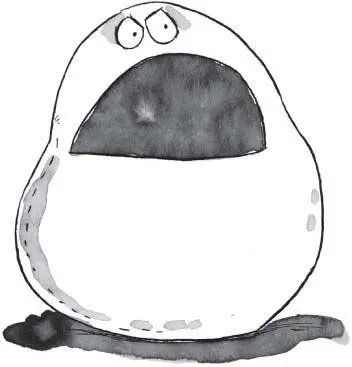

You will now want to know what a Brollachan is and I will tell you. A Brollachan is a dark, splodgy, shapeless thing. It has two red eyes, an enormous mouth and absolutely nothing else whatsoever. A Brollachan has no bones and no stomach and no nose. It has no arms and no legs and no feet and no toes and therefore no toenails. And it has no hair. There is probably nothing with less hair than a Brollachan.

A Brollachan, then, is just a squashy and quite frightening blob which rolls about the place. But though it has no shape of its own a Brollachan can take on the shape of things that it meets. A Brollachan lying on a table, for example, might become table-shaped or a Brollachan looking at a round Dutch cheese could become cheese-shaped if it wished. And though it cannot really think it can hear a little through its bulges and it can certainly feel.

The Brollachan that this story is about lived in a house beside a swampy pond with his mother, who was a Fuath. Fuaths are evil and bad-tempered fairies who live near water, so they are often dripping wet. They look almost like ordinary ladies but if you look at them carefully you will find that there is something odd about them. Sometimes they are hollow from behind, and sometimes they have only one nostril.

The Brollachan’s mother had a long nose with a black wart on it, whiskery ears, one frightful long tooth and webbed feet. She was a worrier and she was a nagger. She wanted the Brollachan to be more scary and more shapeless than he was. She wanted him to lure people into the swamp by terrifying them with his vile red eyes. She wanted him to bubble disgustingly in the mud at the bottom of the pond and she wanted him to speak.

Читать дальше