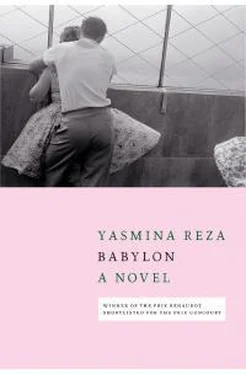

* * *

At one point Lambert was heard to say, “All the leftwing ideas are deserting me little by little.” To which Jeanne replied, with a boldness that would have been suicidal a few years back among this same bunch, “Me they never did get to!” “Me neither,” Lydie chuckled, utterly comfortable among the company. “Lambert neither!” Pierre said. “What are you talking about, my whole life I voted left, through hell and high water!” said Lambert defensively. “People even accuse me of being a hard-core old lefty.” Serge claimed the title for himself alone in the room, and someone asked if “lefty” could be translated into other languages. Everyone threw out words, by common consent ruling out the possibility of any real English-language equivalent. Gil Teyo-Diaz, our expert in things Hispanic, offered “progré,” citing as he did so the bearded hero of the strip Quico, el progré. I said, “And what about in Italian, Jean-Lino—how would you say it?” I saw him redden, embarrassed at being thrust forward suddenly; he looked for a little help from his wife, who shrugged impatiently, he stammered something or other and wound up offering “sinistroide.”

Sinistroide! The word brought laughter and someone asked if you could say un vecchio sinistroide . He said he didn’t see why not, but that since he wasn’t an Italian from Italy, he wasn’t certain of the term, anyhow he couldn’t say anything for sure on the matter, the only Italian he spoke was with his cat, and they never discussed politics. This charmed the crowd and he inadvertently became a pet of the evening.

* * *

“Youth is departing!” Serge cried when Emmanuel tried to sneak out. The poor kid had to come back into the living room to make the farewell rounds. I had seen him standing before Lydie for a long while, curiously bent over, and then I realized she had taken his hand and was talking to him without releasing it, as do people who are confident of their personal magnetism and whose age allows them some physical familiarity. Catherine asked Jean-Lino if he had any children. His face brightened, he spoke of a joy that had come to him from heaven and Rémi’s name reached his lips. Perhaps people invent their joy. Perhaps nothing is real, neither joy nor sorrow. Jean-Lino called “joy” the surprise, the unexpected thing: the presence of a child in his life. He called “joy” the surprise of tending to another being, of being responsible for someone. That’s the way Jean-Lino was made. The infernal Rémi was joy fallen from heaven.

* * *

As Emmanuel left, Etienne and Merle Dienesmann arrived. Merle had just performed (she’s a violinist) in the Dvořák Requiem at Sainte-Barberino church. Etienne is Pierre’s closest friend. For the past few months, his life has been changing. In his garage he is stockpiling light fixtures that he buys because of his late-stage macular degeneration. He categorically refuses to talk about the condition in company and acts as if nothing is wrong (which is becoming less and less possible lately). Their garage has no electricity, so when he enters that enclosure to deposit or to pick up the item that’s supposed to help him see, he sees nothing unless he goes in with a thousand-watt flashlight. Etienne was a math professor like Pierre, now he teaches chess to kids for various organizations. I’ve never heard him complain of his condition. His eyes are losing their brilliance bit by bit, but something else, I don’t know how to define it, has come to his face—endurance, nobility. Merle too acts as though nothing is happening, but I see her imperceptibly bring her glass a bit closer to the bottle when Etienne is pouring, or make some other infinitely small gesture that bowls me over.

* * *

Jeanne spent half the party, cellphone and spectacles in hand, absorbed in some feverish conversation. Serge acted like he noticed nothing. Playful, teasing (adorably heavy-handed), bellhop and headwaiter, talking to everyone, even trying to amuse Claudette El Ouardi, he made things light and easy for me. Even if he has got over being jealous of Jeanne’s present life, I couldn’t understand such crass behavior from her. I found my sister monstrous. A pathetic woman in her gamine spike-heel sandals, indelicate and vulgar. Passing close by her, I said, Stop, be with us a little. She looked at me as if I was embittered and irritating, and she just moved a few steps away. It nearly ruined the evening for me, but then, seeing her from behind—leaning into her phone, her dyed hair tumbling down over her bison-hump back, engulfed for so many years in the banality of life—I thought she was absolutely right to grab at this coxswain-cocksman guy, and the whip and the dirty talk, right to not worry about the jovial ex-husband, about proper behavior, while there was still time.

* * *

Gil Teyo-Diaz and Mimi Benetrof were just back from southern Africa (everyone travels but us). Gil told about how he had found himself nose to nose with not one, not two, but three reclining lions. Man and beasts sized each other up, he said, and none of them budged! “No one budged because the lions were five kilometers away and you were observing them through binoculars from the jeep,” Mimi said. We laughed. Danielle laughed, her body stuck to Mathieu Crosse. Then in the far south of Angola, Gil went on, we were in a boat on the Kunene River where it was infested with crocodiles. According to Mimi, they had seen one baby croc on a rock—it might also have been a branch—and it was in northern Namibia. Gil declared that he had taken photos of terrifying crocodiles from less than six feet away. Sure, Mimi said, he took them at the Johannesburg zoo. She’s talking nonsense, said Gil, and “anyhow we’re not about to go on a trip like that again, now that Mimi isn’t earning a cent anymore. My wife works in the reinsurance business, in the department handling Acts of God, the term for natural disasters, which in our times, given the climate craziness, means: Goodbye bonus!” Everyone laughed. The Manoscrivis laughed. That’s the picture of them that we’ve still got: Jean-Lino, in his violet shirt and his new yellow half-round glasses, standing behind the couch, flushed from the champagne or the excitement of being out in society, all his teeth showing. Lydie, seated below him, skirt spread to either side, her face tilted left and laughing hard. Laughing probably the last laugh of her life. A laugh that I ponder endlessly. A laugh without malice, without coquetry, that I still hear resonating with its playful notes—a laugh unthreatened, suspecting nothing, knowing nothing. We get no advance warning of the irremediable. No furtive shadow slipping about with his scythe. When I was little, I used to be fascinated by the hooded skeleton whose dark contours I could see in a lunar halo. I still harbor that idea of premonition, in some form or another—a chill, a light suddenly dimming, a chime—who knows? Lydie Gumbiner did not sense anything coming, any more than the rest of us. When the other guests learned what happened hardly three hours later that night, they were stunned, and frightened. Nor did Jean-Lino feel the faintest grim brush when a few minutes later he started talking mindlessly—infected without realizing it by that conjugal behavior that involves taking center stage and teasing the partner to entertain the group. How could he have sensed anything? The situation felt familiar and inconsequential. Just some Saturday-night silliness—men reshaping the world, kidding around—turning edgy.

* * *

* * *

Lydie asked whether the chicken in the Lallemants’ loaf came from an organic farm source. Sounding a little put out, Marie-Jo replied, “I honestly have no idea. We got it at Truffon.”

Читать дальше

![Ясмина Сапфир - Охотница и чудовище [СИ]](/books/35157/yasmina-sapfir-ohotnica-i-chudoviche-si-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог резни [=Бог войны]](/books/63616/yasmina-reza-bog-rezni-bog-vojny-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог войны [=Бог резни]](/books/63617/yasmina-reza-bog-vojny-bog-rezni-thumb.webp)