* * *

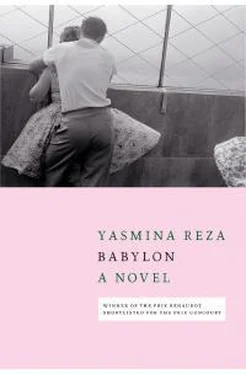

The Lallemants had just got back from Egypt. Lambert laid out photographs of pyramids with always one or two Asians in the frame, shots of Cairo, storefronts with dummies in them, and then one unusual image. I said, “Oh let’s see, let’s see that!” It was nothing: a woman viewed from the back walking with a little child. The shot was almost random, not very sharp. I can pull it up today on my computer because Lambert sent it to me online right then (which is why in my album it comes just before the picture of the Manoscrivis laughing). In a street in Cairo, a woman is walking holding the hand of a tiny girl in a long white dress. The street surface there is tiled, probably an esplanade or a broad sidewalk. It’s nighttime. All around are men, signs, overlighted shopwindows. The woman is voluminous, her hair concealed by a scarf. It’s hard to work out exactly how she’s dressed, over a black sweater and dark trousers she’s got a kneelength orange tunic. The child comes up to just above her knees, she’s all in white except for her bare arms. A kind of priest-like dress with panels, very long, that grazes the ground and must hinder her walking, under that a loose shirt up to the neck. The dress flares out from the waist, the way it would for an adult style, with a notable sweep of fabric. Up top, there’s the child’s very small head. The nape of the neck is naked except for a tail of braid down the middle, her hair is thin and black, the ears protrude. How old is she? That dress doesn’t suit her at all. She’s been dolled up and marched out into the night. I immediately identified with that figure in white being launched into years of shame. When I was a child they were always making me pretty . I understood that I wasn’t naturally pretty. But people shouldn’t dress up an unlovely child. She’ll feel abnormal. I saw the other children as harmonious. I felt ridiculous in old-lady clothes that kept me from fidgeting, my hair always cut short (throughout my entire childhood my mother forbade me long hair) and pinned back with a barrette to control the curl and bare my forehead. I remember a period when I would do my homework with fake-hair pieces clipped onto my own; I would shake my head regularly to feel them swing and bounce. My mother wanted me to make a good appearance. By which she meant tidy, slickedback, constrained, and ugly. This woman in the headscarf wasn’t thinking of the little girl’s well-being. She felt nothing like that in her own body. But mostly, there is no concern for well-being. No one thought of such a thing in our house. I cannot forgive that bitch Anicé for scorning my mother’s doily. I can’t sleep thinking of it. She was really nice, your momma! meaning to please me. Or to reproach me. My mother was anything but nice. It was impossible to describe her in those terms. On the pretext of death, people strip a person of their essential character. What would have pleased me, instead, would have been for that bitch to take the placemat tenderly, lay it carefully into her bag, treat it at least for the few seconds of farewell as a cherished object. She probably tossed it into the nearest trashcan. I would have done the same, but no one would suspect it. When I wasn’t part of a social display, my mother would drag me around like that Cairo mother, preoccupied with other life concerns. When her hands were taken up by the shopping cart, I was supposed to hold onto its side rail. I could trot along for miles with snot running from my nose and my hood askew on my head and she’d never notice. Jeanne and I were always overdressed. Until we were quite old we had to wear hoods for six months of the year. What detail was it that caught my eye when Lambert laid out his inert photographs before us? That pair walking the greenish tile pavement caught me up short. Despite the disproportion between the two figures, the overwhelming mother and the child with the pin-like head, you could grasp the whole force of their tiny life. No matter that the photo was taken only a few days before my party, in a different country, a different climate; still it grabbed me and thrust me way back in time. We were ugly, and ill-dressed, my mother and I. We used to go all alone through the streets in that same way, and even though my mother was not large, I felt very small alongside her. Emptying her apartment with Jeanne, I understood how alone she had been throughout her life. When my father had his bouts of madness and hit me, she would turn up in my room to ask me to stop crying. She’d appear on the threshold and say, “All right now, that’s enough theater.” Then she would go cook dinner and make some dish I liked—a noodle soup, say. In the last months of her life, when we came to visit her, she was possessed by some inexplicable liveliness. Neck straining forward, face at the ready, on the watch for any movement, she was determined not to miss a word exchanged in her presence, and this was despite her deafness. She who all her life had made a specialty of indifference, who had taken a negative counterposition on everything, when it came time to throw in the sponge she was devoured by curiosity.

* * *

There’s always some millstone character at these things. That evening the millstone was Georges Verbot. He eats, he drinks, he never helps out, and he doesn’t talk to anybody. The snow had turned to a soft rain. Plate and glass in hand, Georges Verbot wandered aimlessly among the groups, then went to stare out the window as if to say the scene was at least slightly more interesting outdoors. I was furious that Pierre had invited him again. There’s this tendency among many men, I’d noticed, to drag along through their whole lives these annoying millstones whom they find entertaining while nobody else understands why. Way back, Georges was a historian, then he drew comic strips, now he scribbles and just gets by, drinking all the way. He still has a vaguely handsome face that attracts women who have nothing much going on. Catherine Mussin, who still works for Font-Pouvreau, edged over to the window and tried a little opener about the changeable weather. Georges said he liked lousy weather, rain, especially this kind of dismal rain that pisses everyone off. Catherine gave a nervous laugh, charmed by the picturesque. He asked what she did, she said she was a patent engineer, he replied, “Same bullshit as Elisabeth!” She laughed again and explained that the point was protecting a researcher’s inventions.

“Oh yah. And what invention are you protecting these days?”

“I’m working on Di-opiomorphine. An application for a patent for a new analgesic, that is.”

“And what’s your application going to do? Help those guys make a fortune?”

She tried to introduce some nuance. By this point she must already have gotten a good whiff of liquor breath. Georges said, “A real researcher doesn’t give a damn about the bucks, my girl, he doesn’t need his work to be protected!”

Catherine tried to put in the term “public interest” but to absolutely no avail.

“You folks are the worker bees of the industrial world,” Georges went on. “The guys who discovered the AIDS virus didn’t give a damn for the money, what interested them was basic research, basic research doesn’t need you my darlings, your patent fuss is just commerce plain and simple, you’re not protecting anybody, you’re protecting the bucks.”

He’d cornered her between the window frame and the chest, he was talking into her face from two inches away. She was suffocating and started shouting, “Don’t be so aggressive!” People turned around and Pierre stepped in to control his friend. The Manoscrivis took Catherine in hand, making her a plate of salad and bread with the Lallemants’ chicken loaf. She kept saying, “Who is that guy? He’s crazy!” As I passed by Lydie I said, “There’s a fellow you ought to do your readjustment thing on!” “Can’t adjust an alky,” she informed me. I wondered who she did adjust if you couldn’t do it to lunatics.

Читать дальше

![Ясмина Сапфир - Охотница и чудовище [СИ]](/books/35157/yasmina-sapfir-ohotnica-i-chudoviche-si-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог резни [=Бог войны]](/books/63616/yasmina-reza-bog-rezni-bog-vojny-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог войны [=Бог резни]](/books/63617/yasmina-reza-bog-vojny-bog-rezni-thumb.webp)