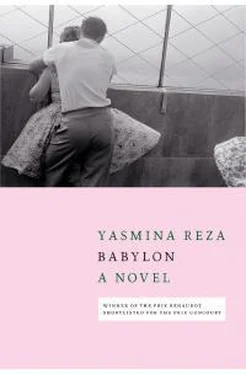

Ясмина Реза - Babylon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ясмина Реза - Babylon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Seven Stories Press, Жанр: Проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Babylon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Seven Stories Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:9781609808334

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Babylon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Babylon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Babylon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Babylon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Jean-Lino doesn’t know what to do. Leave her stewing and go have his smoke, or stay and try to smooth things over. She was sitting at her desk, a little antique writing table in the living room, she’d put on her glasses and was reading her emails on the laptop with the look of a woman getting back to things worth her interest. He’d never seen her do her mail at night. Making up looks like a long haul. He decides to go out and have his smoke. He puts on his biker jacket and leaves. He takes the stairs down. Reaching our floor, he hears the sound of voices. People are leaving our apartment and standing around on the landing to wait for the elevator. He thinks my sister and Serge are probably in the group. He hears laughter, hears my charming voice (the word he used). Even though the door separating the stairwell from the landing is closed, he moves back up a few steps to avoid being seen. He has lost all confidence. He’s ashamed. An hour earlier he’d been part of that merry band, he’d felt included, maybe even appreciated at certain points. Now he doesn’t even want to risk running into any of them downstairs. Even when these people have left, others might still come along. When he hears the elevator set off and our apartment door close, he climbs back up to the fifth floor. He sits down on the highest step, on the worn carpeting, and lights his cigarette. It’s the first time he’s smoked in the stairwell. He’d never thought of it before. He thinks back over the evening. He smiles as he reviews the good moments, he didn’t feel the mockery when he was making people laugh, but maybe he’s naïve. He and Lydie—they aren’t used to going out, at least not to this sort of gathering. At the beginning, they’d been a little shy, but they’d soon felt comfortable. He’s no longer sure of anything. All he knows is that he was happy and now he isn’t. And that somebody did something that deprived him of his high spirits. I understood him better than anyone, he’d found somebody to talk to. My father didn’t know how to lose his temper without hitting. At dinner once when I was feeling cheerful, I spiked up a potato from the platter with a knife and stuck the thing whole into my mouth. I got a smack instantly and I still feel the scorch of it today. Not because he’d hit me—I was used to that—but because he had shot down my high spirits. Jean-Lino has a sense of some injustice. He sees himself, doubled over on the top step in his leather jacket, in the horrid light of the stairwell. Lydie’s words about Rémi come back to him. He had managed to avoid hearing them too well; he’d had a few drinks and that helped. But everything was gone, vanished—the pleasure, the euphoria. Did the boy despise him? Jean-Lino didn’t believe a child that age could feel such a sentiment, but she’d also said he knew nothing about children. He’d given up on Grampa Lino , was hoping for something else, something more substantial and deeper. The last time he saw Rémi, he’d taken him to the zoo with its amusement park. It was a weekday, during the school winter break. On the Metro he’d bought the boy a laser pen from a hawker. The ride was long, with changes. After tracing zigzags on the floor and the walls, Rémi had begun attacking the passengers with his ray pen. Jean-Lino told him to aim just at the feet but he raised the beam surreptitiously to people’s faces while pretending to be looking elsewhere. People yelled and Jean-Lino had to confiscate the toy until the zoo stop. Rémi sulked. Even when they reached the park he lagged behind. He brightened at the trick mirrors, breaking up over the distorted shapes they made of his body and especially of Jean-Lino’s. They went on the Enchanted River trip, the bumper cars, the Russian Mountains, the place wasn’t crowded and they could do it all with no waiting. Rémi flew the airplanes, at the game booths they won a plush monkey, a water pistol, a bubble blower, a boomerang ball, Rémi ate a chocolate crêpe and they shared a cone of cotton candy. Rémi wanted to ride a dromedary—he’d seen that in a picture at the entry gate—and they looked for the animals but there were none; they’d be back in the springtime, like the ponies, they were told. Again Rémi sulked. They went to the playground. Jean-Lino sat down on a bench. Rémi too. Jean-Lino asked if he’d like to climb the giant spiderweb. Rémi said no. He burrowed his head into his parka hood, leaving his new toys scattered about him as if he’d stopped caring about them. Jean-Lino said he’d finish his cigarette and then they’d leave. A boy Rémi’s age walked past them, playing railroad train and marking a track in the sand ahead of him with a branch. Rémi gazed after him. The kid came past again and stopped. He pointed to their bench and said, That there is the Maleficia Station. Rémi asked where he’d gotten the branch, they went off together to a little clump of bushes. Two minutes later they tore past Jean-Lino; Rémi had become a train. After several circuits they abandoned their branches and climbed into the toboggan slide from the bottom. They emerged giggling from the top, knocking over the little kids who’d just come up the ladder. They did all sorts of things around the playground, they dug through the sand down to the concrete, they conferred awhile leaning against the doorpost of a wooden hut, they climbed around the giant spiderweb and played at hanging dangerously from it. Rémi was livelier than Jean-Lino had ever seen him. Even from a distance, he could feel the boy’s overexcitement, the urgent complicity with the new friend. He also saw Rémi’s desire to conform, his submission. Jean-Lino felt cold. He made occasional signals to the boy, who didn’t see them. He was tired of waiting there on the hard bench. Dusk was coming on. And he was feeling something he couldn’t admit to—a sense of abandonment. As he thought back on that afternoon in the park now, alone in the service stairwell, melancholy gripped him again. He remembered the toys he’d had to go around picking up and stuffing into a cotton sack he bought at a kiosk. Rémi had refused to carry it, and Jean-Lino had slung it across his own back and lugged it home himself. Aside from the bubble blower, the other toys had never come out of the bag since. In the Metro, Rémi had fallen asleep against his shoulder, and had put a hand into his as they crossed streets on the way home. Lydie’s words darken those pictures. He doesn’t know what to think anymore. The words have seeped into his body and are bleeding him uncontrollably. Jean-Lino crushes out his cigarette on the concrete step, he slips the stub beneath the carpet. His feet look skinny in his dress loafers. He feels small—in size, in everything.

Some days, when I wake up, my age hits me smack in the face. Our youth is dead. We’ll never be young again. It’s that “never again” that’s dizzying. Yesterday I reproached Pierre for being soft, easily satisfied with little. I finally said, “You let life just go by.” He cited a colleague, an econ professor who’d died of a heart attack a month earlier, he said Max gobbled up life, one project after another, look what it got him. That makes me a little blue, it’s hard to keep projecting forward. But maybe the very idea of the future is destructive. There are languages that don’t even have a future tense.

The Americans has become my bedside book. Ever since I opened it again, I leaf through it a little every day. In Savannah an afternoon in 1955, which is the year all the photos in the book were taken, a couple is crossing a street. He is a soldier in uniform, shirt and peaked cap. He might be about fifty, pipe in his jaw, relaxed in that American way, despite his pudgy body and the potbelly sliced at the middle by his waistband. The woman is much shorter even in heels and she’s holding onto his arm in the old-fashioned way, by the crook at his elbow. Robert Frank has caught them full front, both looking into the lens. She is well turned out, molded into a dark pretty dress trimmed at the pockets and neck, with patent-leather pumps. She’s smiling at the photographer. She looks older than the man, a face lined with difficulties, anyhow that’s what I see. You think right off that it’s not every day she goes strolling on a man’s arm, that she’s having a day of splendor with her new handbag, her girlish hairdo, her strapping fella in his officer’s cap. It was a Sunday of life like you get sometimes, when good luck befalls you. The first time I saw Lydie, she was crossing the lobby and leaving the building on Jean-Lino’s arm. In mid-afternoon, she too dressed to the nines, all done up and head high, proud of herself, of her life, of her little pockmarked man. They had just moved in. Maybe she never walked out that door again with the same radiant satisfaction. We all do that at some point, man or woman—strut out on somebody’s arm as if we were the only one in the world to have hit the jackpot. We ought to hold onto such flashes of glory. We can’t hope for anything in life to last. I talked to Jeanne on the phone: her adventure is losing steam. The picture-framer is less and less eager and more and more dissolute. When our mother died Jeanne tried to use the sad event to bring a touch of sentiment into the relationship. The boyfriend made clear he didn’t much care and sent her a lot of hard-core messages as the days passed—he wants to drag her to orgies and offer her to other men, etc. When she resists, he turns aggressive. Jeanne calls me almost every day, half-crying. She tells me, “He puts these pictures in my head, now I feel like I want to go and see. But I’m not up to it. I’m vulnerable. I’m alone. I have no railing to hold onto, to take a slide into hell you need a railing, I slide down and I stay at the bottom.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Babylon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Babylon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Babylon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Ясмина Сапфир - Охотница и чудовище [СИ]](/books/35157/yasmina-sapfir-ohotnica-i-chudoviche-si-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог резни [=Бог войны]](/books/63616/yasmina-reza-bog-rezni-bog-vojny-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог войны [=Бог резни]](/books/63617/yasmina-reza-bog-vojny-bog-rezni-thumb.webp)