Ясмина Реза - Babylon

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ясмина Реза - Babylon» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2018, ISBN: 2018, Издательство: Seven Stories Press, Жанр: Проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

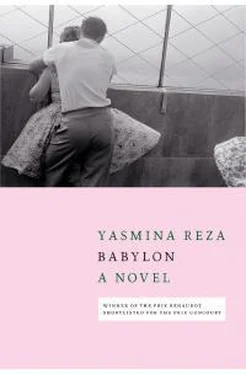

- Название:Babylon

- Автор:

- Издательство:Seven Stories Press

- Жанр:

- Год:2018

- ISBN:9781609808334

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Babylon: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Babylon»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Babylon — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Babylon», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“The day before yesterday, he drank too fast and he started coughing, coughing, choking.”

“What do you mean to do about Lydie?”

“I’m going to call the police.”

“Yes. Of course.”

“Where’s Pierre?”

“He went to sleep.”

The cat was calmly drinking its yeast. The box of fish patties sat on the table. Given the label, I thought there must be some sort of anti-anxiety drug in the formula. Jean-Lino was still leaning his head against the animal’s muzzle. His voice had grown stronger since he appeared at our door. The look of his face and his mouth, too. I had known the champion of The Mouth in Search of a Form: Michel Chemama, my English teacher at the Lycée Auguste Renoir, a Jew from Algeria, forever linked to the words “Haaarvestiiing meuchiiiine,” pronounced with the lower lip thrust forward (for years, and still today, I have puzzled over the urgency of teaching the term “har-vesting machine” to French city kids just beginning to learn English). Jean-Lino set the syringe down on the table. Eduardo slipped to the floor and left the kitchen. We did not speak. I really liked Michel Chemama, always in his gray flannel trousers, his double-breasted navy blazer with its metal buttons. He may still be alive. As a child you can’t judge a teacher’s age, they all seem old. It was nice of you to come back, Jean-Lino said. What happened, Jean-Lino? I wouldn’t have chosen to be so direct, but nothing else came to mind. Language transmits only the obstacles to expression. You’re aware of that in normal circumstances and you work around it. Jean-Lino shook his head. He leaned forward to pick up a mandarin orange from the counter. He offered me one. I refused. He began to peel his. I said, “The two of you looked happy at home.”

“No.”

“No?”

“Well, yeah— I was . ”

“Don’t feel you have to—”

He set the mandarin down on a bit of the peel, pulled apart a segment and took off the threads of white pith.

“I don’t feel anything now. Am I a monster, Elisabeth?”

“You’re anesthetized.”

“I cried when it happened. But I don’t know if it was from sadness.”

“Not yet.”

“Ah—yes . . . Yes, that’s it. Not yet.”

He took up, one after the other, the orange sections and cleaned them without eating them. I was dying to ask him, What do you plan to do with Eduardo, but I was afraid of immediately easing his way by my question. I also wanted to ask him about his new glasses. A person doesn’t change unthinkingly from dark rectangle to sand-colored half-round. The thick frames still hinted at his baby face. Among the unknowable elements that cause you to move toward a person and love him, there’s the face. But no facial description is possible. I looked at the long nose that lifted and spread at the tip, the long part underneath, a straight line down from nostrils to mouth. I thought about his teeth, going every which-way, the complete opposite of today’s dental style. While he fiddled with the orange peel, I registered forever the three things Jean-Lino’s face expressed all at the same time: goodness, suffering, gaiety. I said, “I never saw those glasses before.”

“They’re new.”

“They’re nice.”

“They’re from Roger Tin. Acetate.”

We smiled. For sure, it was Lydie who’d chosen the glasses. He would never have reached for that fashion color on his own. There was a racket from the bedroom. I leapt to my feet and pressed my body absurdly against the fridge. Jean-Lino went to see. I was ashamed of my reaction. I mean, if Lydie had actually waked up that would be good news, why be frightened? No, no, the dead awak-ening has always been terrifying, all of literature says so. I stood in the kitchen doorway and listened. Unalarming sounds, Jean-Lino’s Italian voice. I heard him close the door to the bedroom, the corridor plunged into darkness, and he reappeared. Eduardo had tried to jump from the chamber pot to the night table but the lid had slid off, he missed the jump and knocked over the bed lamp. JeanLino sat down at the table again. So did I. He took out a Chesterfield. “May I?”

“Of course.”

“He’s got no experience there—normally he’s not allowed in the bedroom.”

I did something I hadn’t done in thirty years. I took a cigarette and lit up. I drew the smoke right into my lungs. It snagged at my throat and I found the taste disgusting. Sometimes during school vacation, Joelle and I would go to stay near her family’s place in the Indre. They would lend us a little farmhouse outside Le Blanc. We’d say, “We’re off to see the yokels.” One night at supper my right arm started to twitch in a kind of Saint Vitus’ dance, I couldn’t pick up a fork, I’d smoked two packs of Camels in the course of the day, I was thirteen. Later I smoked again a little with Denner. Jean-Lino took the cigarette out of my hand and stubbed it out in the promotional ashtray. I dared to do another thing I would never have done any other time: I stroked his pitted cheek. I said,

“What’s that from?”

“My scars?”

“Yes . . .”

“Acne. I used to be covered with pimples.”

He smoked gazing around the kitchen. What was he thinking about? Me, I was picturing Lydie stretched out dead in the other room. It was both enormous and nothing at the same time. The house was calm. The Frigidaire was sending out its hum. When we were emptying our mother’s apartment, my sister and I found a bunch of her office supplies in a drawer. The stuff was years old, from when she kept the accounts at the Sani-Chauffe company. A case holding a ruler, a four-color Bic pen, staples, a brand-new ream of paper, scissors that could cut for the next hundred years. Objects are bastards, Jeanne said. Again I asked Jean-Lino what had happened.

When they got upstairs, Lydie accused him of humiliating her in company. That he could go back over the episode at the Carreaux Bleus restaurant with his caricature of the chicken was a betrayal in itself, plus the fact of mixing Rémi up in the story. He shouldn’t have mentioned Rémi, Lydie said, and certainly not to report that the boy had made fun of her, his grandmother, which besides wasn’t true. Jean-Lino, still in euphoric spirits, replied breezily that he hadn’t meant any harm, that he’d told that whole story carried away by the hope of making people laugh, which often happens at parties like that, and in fact everybody did laugh good-humoredly. He reminded her how even she had wound up laughing, back there in the restaurant when they’d imitated hens fluttering. Lydie flew into a rage, claiming that she had only laughed (and not much) to cover for him, JeanLino, in the boy’s eyes—to keep the child from realizing, given his ultrasensitivity, how upsetting the imitation was. She would never have imagined, she added, that on top of that she would have to relive that ridicule among strangers, and she pointed out that the performance at the party was applauded only by that belligerent drunk. She scolded him for not seeing her stiffness or her subtle signals, and generally for a lack of sensitivity toward her. Jean-Lino tried to protest, because if there was ever a man attentive to her, and even on the alert, it was he, but Lydie was immured in her complaints and would have none of it. That chicken story, told—alas yes—with the sole purpose of setting off some stupid laughter, revealed his insensitivity, not to say his mediocrity. She had always accepted that he chose not to adopt her way of life, as long as she felt respected and understood. Which was obviously not the case. Yes, some creatures do have wings instead of arms! And thus they flutter and roost. At least—she added as if aiming at Jean-Lino himself— they do as long as the cowardice and thoughtlessness of men didn’t make it impossible for them to do so. What was funny about that? She didn’t understand how people could laugh at lives that are miserable from birth to the slaughterhouse. And drag a child of six into the laughter, to make him into the torturer of tomorrow. Animals only want to live, to peck, to munch grass in the fields. Men throw them into terrible confinement, into factories of death where they can’t move, or turn around, or see daylight, she said. If he really cared out the boy’s welfare and not just winning him over with some loathsome attitudes, these are the things he should be teaching him. Animals have no voice and can’t demand anything for themselves, but by luck, she boasted, there were people in the world like Grandma Lydie to register complaints on their behalf: that’s what he could have taught Rémi, instead of making fun of her. Generally speaking, she blamed him for coming on to the boy at her expense ( Jean-Lino took offense at the term, completely wrong, a term she chose just to mortify him needlessly)—the only strategy he could find, she said, to work up a little complicity with him. She said his behavior was pathetic, that he meant nothing, absolutely nothing, to the boy and would never be his Grampa Lino. She said she was outraged that he should call him our grandchild when he was nothing to the child, who did have actual grandfathers even though one was dead and he never saw the other one. That such a usurpation, especially in front of her, and among strangers, was an act of great violence, since he knew perfectly well her position on the matter and he’d used the term so casually in a situation where she couldn’t correct him. She said further that he didn’t realize it but the child despised him, because children have no respect for people who try to please them and who do anything they want, especially that kind of child, she said, matured beyond his age by the circumstances of life and endowed with a superior intelligence. When Jean-Lino tried to cite the recent signs of affection Rémi had shown him, she was quick to say that all children, Rémi no less than any other, are little whores. And on the pretext of disabusing him, she took the occasion to remind him of his inexperience in that realm. She said that a man who went dotty like that lost all sex appeal for any normal woman and that she had seen quite enough of that behavior already over Eduardo. That she had managed despite herself to put up privately with the spectacle of his regression, but had never expected to see it play out in plain daylight. “In a couple,” she said, “each party has got to make some effort to do the other honor. How a person conducts himself affects what people will think of his or her partner. What good are the violet shirt and the Roger Tin frames if he goes off on dwarf arms and clucking? When I put on my coral earrings and my red Gigi Dool shoes, when I cancel two patients to get a hair coloring and a manicure on the very morning of a party, I do it to measure up to what I believe Your Wife should be, I do it to honor you. And that goes for every realm. And then when we come together with people who are refined and intellectual, she went on, my husband drinks like a tank, acts like a chicken, tells anyone who’ll listen that my grandchild makes fun of me, that the waiter makes fun of me—I’d forgotten that guy—and that my husband himself makes fun of me by twisting a story on a subject that shouldn’t be a laughing matter and that nobody understands is really serious.” Jean-Lino pointed out (or tried to) that several people at the party had taken her side. “No, no, no,” Lydie said, “only one person, and even her—it was that ice-cold researcher lady. You saw how she looked when I said I sing. Even your darling Elisabeth, your dear friend, didn’t say anything. All those people who’re supposed to be in science or whatever don’t give a damn. They don’t worry about a thing, their brains stop at their specialty. And they’re probably the people who developed the antibiotics they stick into the industrial pig farms. The crazy guy was right about that: The men stuff their bellies and their pockets too. They don’t give a damn about the hideous slaughterhouses, they kill off nature and that’s fine with them. And you don’t care either, all you care about is going downstairs to smoke your lousy Chesterfields.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Babylon»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Babylon» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Babylon» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.

![Ясмина Сапфир - Охотница и чудовище [СИ]](/books/35157/yasmina-sapfir-ohotnica-i-chudoviche-si-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог резни [=Бог войны]](/books/63616/yasmina-reza-bog-rezni-bog-vojny-thumb.webp)

![Ясмина Реза - Бог войны [=Бог резни]](/books/63617/yasmina-reza-bog-vojny-bog-rezni-thumb.webp)