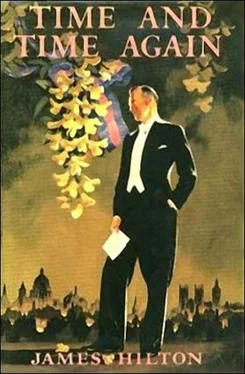

Джеймс Хилтон - Time And Time Again

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Джеймс Хилтон - Time And Time Again» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1953, Жанр: Проза, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Time And Time Again

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1953

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Time And Time Again: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Time And Time Again»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The protagonist, Charles Anderson, leads us through World War I, first love, and the progression of his diplomatic career. Tragedy during World War II almost ends his career.

A continuous thread throughout the novel is Charles' turbulent relationship with his distant and difficult father.

Set in the years just as WWI was ending to the advent of WWII, it is the story of an English diplomat that moves between the past and present.

Time And Time Again — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Time And Time Again», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

But it was this curious interval, during which the first war was not quite forgotten and the next one not yet feared, that made for a sudden short-lived fashion of remembrance. Remarque’s Im Westen Nichts Neues swept the world; so did Sherriff’s Journey’s End. Charles and Jane made up a party to see this play when it came to their city, performed in the language of the country; and afterwards, at a restaurant, memories were unleashed by guests of half a dozen nationalities. For once, it seemed, and perhaps never again, Europeans could unite in a single emotion if not in a common cause; the only faint division line, indeed, was between the ex-warriors and the neutrals who had missed the ordeal. ‘Would you fight again?’ was asked, and the answers of the diplomats were both undiplomatic and unnecessary, for surely they would never have to face the problem. Even an enemy would whisk them safely home across frontiers with full honours.

Charles said to Jane on the way back to their house: ‘I wonder what all our Foreign Offices would say if they got a verbatim report of that conversation. Give us all the boot, maybe.’

‘And then there wouldn’t be any younger generation to take over from people like Papa.’

But Sir Richard also saw the play and discussed it later in an equally undiplomatic way, though privately in his office. ‘Were you in the war, Anderson?’

‘No, sir, I was just too young.’

‘I’d say you were damned lucky then. My son was killed. Makes you wonder —almost—how human beings could be forced to endure such things… I mean if they’d all packed up suddenly and run home—both sides—who could have stopped them?’ This was surely a na ve thought for an Ambassador to utter, and perhaps he realized it, for he continued hastily: ‘Funny the effect a play can have. You ever met this fellow Sherriff?’

‘No, sir.’

‘If I ever do I’ll tell him how much I was impressed.’

‘I’m sure he’d be very glad if you wrote to him and said so.’

‘All right. Draft me a letter… I was in London during one of the Zeppelin raids. Happened to be at Liverpool Street Station—you know Liverpool Street Station?’

‘Yes.’

‘It’s got a very high glass roof… I was in a train just about to leave when a bomb fell. Killed about twenty people in another train coming in across the platform. Hope I never see anything like that again—people on their way to business from the suburbs—lots of girls… I pulled some of them out of the mess—the glass did the worst… I’ll never forget those office girls—cut to ribbons, some of them… Well, well, must work. Fetch me Herstlett, I want to look up something… Oh, and— er—don’t bother about a letter to that writer fellow—might lead to a lot of useless correspondence…’

Charles was transferred again. Already he was beyond the stage at which his work was mostly simple and routine; it began to present problems, and these he thought he tackled rather more than adequately. There were times when he was bored and fancied he would have been happier in some other job, but with later detachment he usually decided that he wouldn’t—he didn’t really envy the lawyers, politicians, and business men whom he frequently had to meet. The ones he did occasionally envy were shy engineers on their way to some project, or a few stray writers globetrotting for local colour and showing off their freedom at all the parties they could pick up en route. There were times also when Charles thought of the millions living around him whom he would never encounter unless they figured personally as servants or tradespeople or impersonally as statistics in books of reference —people who might, by some movement of force beyond the reach of protocol, become suddenly ‘allies’ or ‘enemies’. Like all the great professions, diplomacy seemed to him a marvellous conspiracy that never did, in the long run, quite succeed in either achieving or defeating the ends of something bigger than itself.

He was at a South American post in 1929 when Wall Street crashed and he received a lugubrious letter from Havelock bemoaning the way the London market had dropped in sympathy. Since Charles had American friends whose plight was almost desperate, he did not waste much concern on his father’s financial position, but he was sorry to learn from Cobb that Aunt Hetty was ill. His father had not mentioned it. A few months later Aunt Hetty died, and Havelock did mention the matter then, listing it as another of the crosses he had to bear. But the next letter was reassuring—it enclosed a cutting from The Times, to which Havelock seemed to have contributed the blithest letter of his career. It narrated how, in the churchyard of Pumphrey Basset, Berks., he had discovered the resting-place of a forgotten female dwarf, judging from the inscription on the eighteenth-century tombstone, which read ‘Aged 42 Years, Height 35 inches, “Parva sed apta Domino”.’ Havelock made a good story of it, and Charles pictured him kneeling and feeling on the grassy grave, for (as he remembered from having taken part as a boy in several of these expeditions) the stone was apt to be so flaky and moss-covered that it chipped away if one tried to clean it, and in such cases the sensitive fingertip was often a safer reader than the eye.

Charles was still in South America five years later when the sudden death of Jane’s father summoned her to England. Charles would have asked for leave to accompany her, but he was First Secretary now and it was possible that his chief might also be taking a leave in the near future, so he said he had better stay. Jane agreed with him. What they both meant was that he mustn’t miss the chance of being Chargé for a time. It was only a small Legation, but to have full authority and responsibility at his age, even temporarily, could be a stroke of luck in his career. So little ever happened to stir the placid relations between His Majesty’s Government and that particular country that Jane and Charles tried to cheer themselves, the night before she sailed, by imagining some incident that would give him scope to show his capabilities.

‘If Argentina were to grab the Falkland Islands,’ was Charles’s choice.

‘An earthquake,’ Jane countered. ‘You plunge into the wreckage and save some red boxes.’

They agreed that both these suggestions would involve unnecessary disaster. It was the Commercial Attaché who joined them then and, being admitted to the game, scored easily by his vision of an airman making a forced landing near the top of the Andes. ‘First of all, no one can climb to rescue him but Charles. And then it turns out the fellow hasn’t any passport or visa—a man without a country. But he carries a secret formula that will revolutionize the art of warfare—’

‘In that case,’ interrupted Charles, ‘I’d leave him there.’

‘Which would spoil my point—so I’ll change the formula. It’s for something beneficial to humanity—a cure for bubonic plague or pellagra or foot-and-mouth disease. Anyhow, because of this you promptly confer on him honorary British citizenship.’

‘Having just then decided to invent such a thing,’ Charles interjected.

‘That’s where I get to my point—you take a chance. The Nelson touch—so rare among Chargés d’Affaires.’

This Attaché, Claud Severing, was a young man whom they had come to like and had taken with them on several climbing expeditions. Jane was glad she was leaving Charles with a real friend, and Charles, though he was sorry to see her go, felt that three months of bachelorhood might yield austere pleasures. It would be agreeable, anyhow, to spend so much time with Severing, with a few trips into the mountains if they could be arranged.

Yet after Jane had gone Charles made a discovery that surprised him: he not only missed her but he missed something in himself that seemed to vanish when she left. Perhaps it was the way she managed things in the house, her decisions about parties and party-giving, her advice on small matters of etiquette or behaviour, even her actual help in his work, for she liked to spend time in the Chancery odd-jobbing in a way that would have been impossible in a larger and more systematized Legation. So now his extra work was quite often a symbol of her absence even when he was thinking of other things. When he most acutely missed her was late in the evening after a party, when they would have held their post-mortem on the guests and conversation. Because they were both popular, Charles received a rush of invitations well meant to appease his loneliness, but somehow accepting them only seemed to increase it; he missed the flash of Jane’s eye across the dinner-table, signalling in secret what her partner was like; or the quizzical look which conveyed that she had overheard him say something witty at his end. Without her, indeed, he found it twice as hard to be only half as amusing, and since he had the reputation for being amusing he wondered if his hosts were thinking him bad company or merely realizing what a good wife for him Jane was. He thought so too, but he wished he need not prove it quite so negatively. Partly from this somewhat obscure motivation he began a small flirtation with Madame Salcinet, the wife of the French Minister. She was pert and youngish and apparently ready for the diversion, since the place bored her and her elderly husband was tetchy enough to regard his post as the Quai d’Orsay’s equivalent of Devil’s Island. ‘Of course Edouard will retire after this,’ she confided. ‘There is really nothing for me to do but count the days—and even more depressingly, the nights.’

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Time And Time Again»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Time And Time Again» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Time And Time Again» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.