Klaus Schwab - Stakeholder Capitalism

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Klaus Schwab - Stakeholder Capitalism» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. ISBN: , Жанр: economics, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Stakeholder Capitalism

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:9781119756149

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stakeholder Capitalism: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Stakeholder Capitalism»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Individual agency:

A clearly defined social contract:

Planning for future generations:

Better measures of economic success: Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and Planet

Stakeholder Capitalism

Stakeholder Capitalism — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Stakeholder Capitalism», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Low GDP Growth

As we outlined in Chapter 1 1 75 Years of Global Growth and Development In the 75 years since the end of World War II, there has been a surge of global economic development. But despite this, the world is living a tale of two realities. On the one hand, we have rarely been as well off as we are today. We live in a time of relative peace and absolute wealth. Compared with previous generations, many of us live long and mostly healthy lives. Our children get to go to school, even often college, and computers, smartphones, and other tech devices connect us to the world. Even a generation or two ago, our parents and grandparents could only dream of the lifestyle many of us have today and the luxuries that come with abundant energy, advances in technology, and global trade. On the other hand, our world and civil society are plagued by maddening inequality and dangerous unsustainability. The COVID-19 public health crisis is just one event that demonstrates that not everyone gets the same chances in life. Those with more money, better connections, or more impressive ZIP codes were affected by COVID at far lower rates; they were more likely to be able to work from home, leave densely populated areas, and get better medical care if they did get infected. This is a continuation of a pattern that has become all too familiar in many societies. The poor are consistently affected by global crises, while the wealthy can easily weather the storm. To understand how we got here—and how we can get out of this situation—we must go back in time, to the origins of our global economic system. We must play back the picture of post-war economic development and look at its milestones. The logical starting point for this is “Year Zero” for the modern world economy: 1945. And there is perhaps no better place from where to tell this story than Germany, for which that year was truly a new beginning.

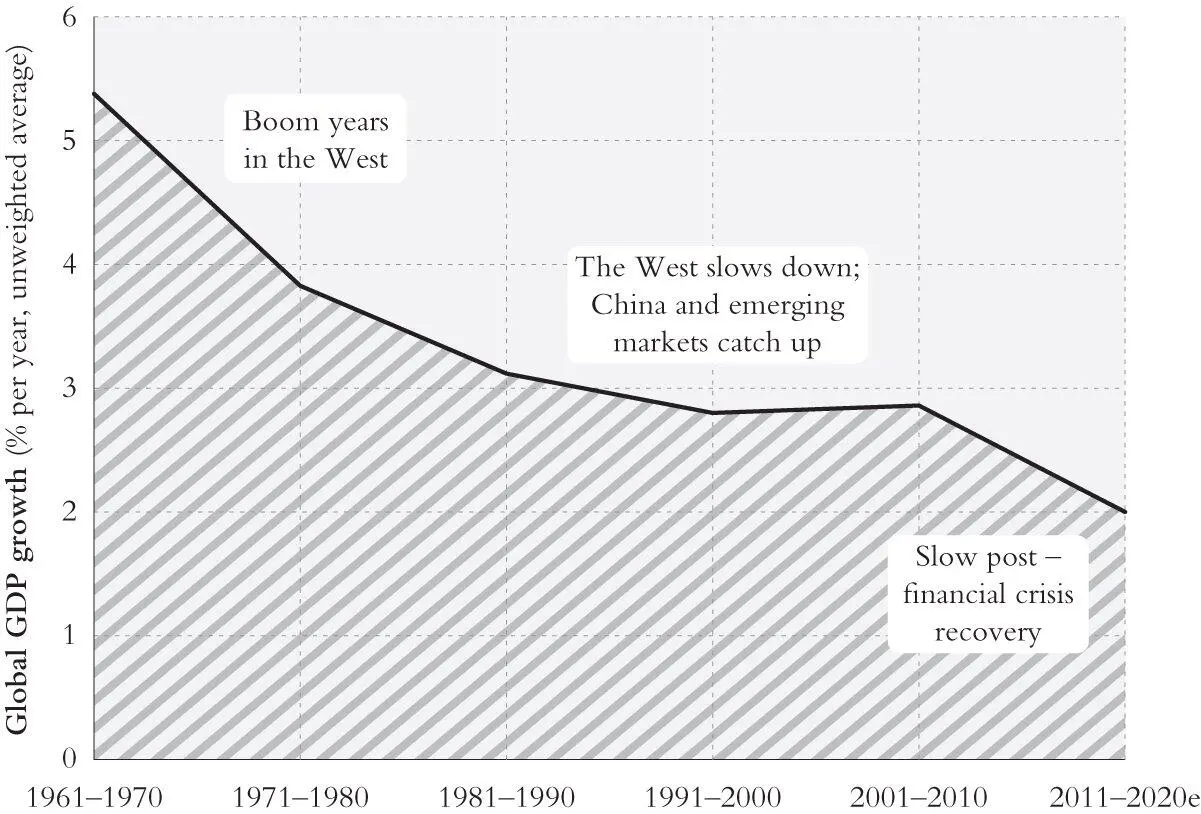

, the global economy in the last 75 years has known many periods of rapid expansion, as well as some significant recessions. But the global economic expansion that started in 2010 has been tepid. While global growth 35 35 Measured in constant 2010 US dollars.

reached peaks of 6 percent and more per year until the early 1970s and still averaged more than 4 percent in the run up to 2008, it has since fallen back to levels of 3 percent or less 36 36 World Bank, GDP Growth (annual %), 1961–2018, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG .

(see Figure 2.1).

The number three matters, because it acted for a long time as a pass-or-fail bar of standard economic theory. Indeed, until about a decade ago, the Wall Street Journal pointed out, “Past IMF chief economists called global growth lower than either 3% or 2.5%—depending on who was the chief economist—a recession.” 37One explanation came from simple math: from the 1950s until the early 1990s, global demographic growth almost consistently lay at 1.5 percent growth per year or higher. 38A global growth rate that was only slightly over the rate of population growth meant large parts of the world population were in effect experiencing zero or negative economic growth. That type of economic environment is discouraging to both workers, companies, and policymakers because it indicates little opportunity for advancement.

Figure 2.1 World GDP Growth Has Been Trending Downward since the 1960s

Source: Redrawn from World Bank GDP growth (annual %), 1960–2019.

Perhaps in response to slowing economic growth, economists have since changed their definition of what constitutes a global recession. But it does not alter the fact we have seen meager global economic growth ever since. As a matter of fact, economic growth of less than 3 percent per year seems to be the new normal. Even before the COVID crisis, the IMF did not expect global GDP growth to return to above the 3 percent threshold for the next half decade, 39, 40, 41and that outlook has been negatively affected by the worst public health crisis in a century.

From the perspective of conventional economic wisdom, this could lead to systemic fault lines, as people got used to economic growth. There are two reasons for that.

First, global GDP growth is an aggregate measure, which hides several national and regional realities that are often less positive still. In Europe, Latin America, and Northern Africa, for example, real growth is edging closer to zero. For Central or Eastern European countries that still have economic catching up to do with their neighbors to the West or North, such low growth is discouraging. It may accelerate the brain drain, as motivated and educated people seek economic opportunities in higher-income countries, thereby exacerbating the problems of their home countries. The same is true in regions like the Middle East, Northern Africa, and Latin America, where many people still don't have a fully middle-class lifestyle and where jobs that offer financial security are lacking, as are social insurance and pensions.

Second, in regions where growth is higher than the average, like in Sub-Saharan Africa, even top-line growth of 3 percent or more per year isn't enough to allow for rapid per capita income growth, given their equally high rate of population growth. Low- and lower-middle-income countries that have posted relatively high growth levels in recent years include Kenya, Ethiopia, Nigeria, and Ghana. 42But even if they were to grow consistently at 5 percent per year for the foreseeable future, it could take an entire generation (15–20 years) for their people's incomes to double. (And that is assuming that most of the fruits of economic growth are shared widely, which often is not the case.)

Rapid progress and shared economic growth, like that seen in China in the early 21st century, require real growth rates of 6 to 8 percent in the least developed economies. Lacking this kind of super boost, the great convergence of economic standards of living between North and South, as predicted by some economists, will materialize very slowly, if at all. As Robin Brooks, chief economist at the Institute of International Finance (IIF) told James Wheatley of the Financial Times in 2019: “More and more, there is a discussion that the growth story for emerging markets is just over. There is no growth premium to be had any more.” 43

Looking beyond GDP does not provide more promising prospects. Other economic metrics, notably debt and productivity, are also pointing in the wrong direction.

Rising Debt

Consider first rising debt. Global debt—including public, corporate, and household debt—by mid-2020 stood at some $258 trillion globally, according to the Institute of International Finance, 44or more than three times global GDP. That number is hard to grasp, because it is so big and because it includes all sorts of debt, going from public debt sold through government bonds to mortgages from private consumers.

But it has been rising fast in recent years, and that certainly is “alarming,” as Geoffrey Okamoto of the IMF said in October 2020. Not since World War II were debt levels in advanced economies so high, the Wall Street Journal calculated, 45and unlike in the post-war period, these countries “no longer benefit from rapid economic growth” as a means to decrease their burden in the future.

The COVID pandemic, of course, brought an exceptional acceleration of the debt load in countries around the world, and especially for governments. According to the IMF, by mid-2021, in the span of a mere 18 months, “median debt is expected to be up by 17 percent in advanced economies, 12 percent in emerging economies, and 8 percent in low-income countries” 46compared to pre-pandemic levels.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Stakeholder Capitalism»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Stakeholder Capitalism» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Stakeholder Capitalism» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.