Charles Burke - Representative Plays by American Dramatists - 1856-1911 - Rip van

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Charles Burke - Representative Plays by American Dramatists - 1856-1911 - Rip van» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: foreign_dramaturgy, foreign_antique, foreign_prose, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

No other actor has ever disturbed the impression that the profound pathos of Burke's voice, face, and gesture created; it fell upon the senses like the culmination of all mortal despair, and the actor's figure, as the low, sweet tones died away, symbolized more the ruin of the representative of the race than the sufferings of an individual: his awful loss and loneliness seemed to clothe him with a supernatural dignity and grandeur which commanded the sympathy and awe of his audience.

Never, said Clarke, who often played Seth to Burke's Rip , was he disappointed in the poignant reading of that line—so tender, pathetic and simple that even the actors of his company were affected by it.

However much these various attempts at dramatization may have served their theatrical purpose, they have all been supplanted in memory by the play as evolved by Jefferson and Boucicault, who began work upon it in 1861. The incident told by Jefferson of how he arrived by his decision to play Rip , as his father had done before him, is picturesque. One summer day, in 1859, he lay in the loft of an old barn, reading the “Life and Letters of Washington Irving,” and his eye fell upon this passage:

September 30, 1858. Mr. Irving came in town, to remain a few days. In the evening went to Laura Keene's Theatre to see young Jefferson as Goldfinch in Holcroft's comedy, “The Road to Ruin.” Thought Jefferson, the father, one of the best actors he had ever seen; and the son reminded him, in look, gesture, size, and “make,” of the father. Had never seen the father in Goldfinch , but was delighted with the son.

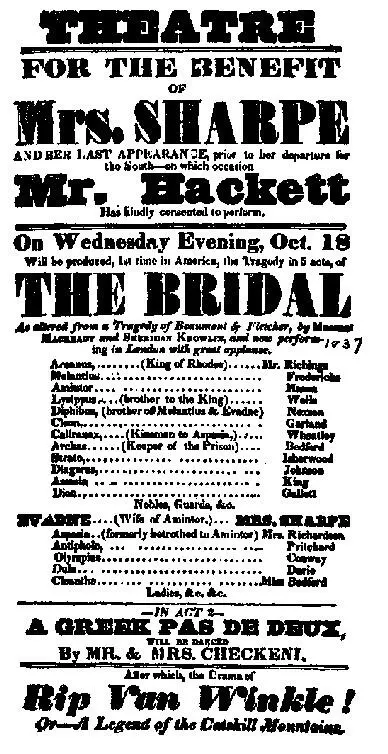

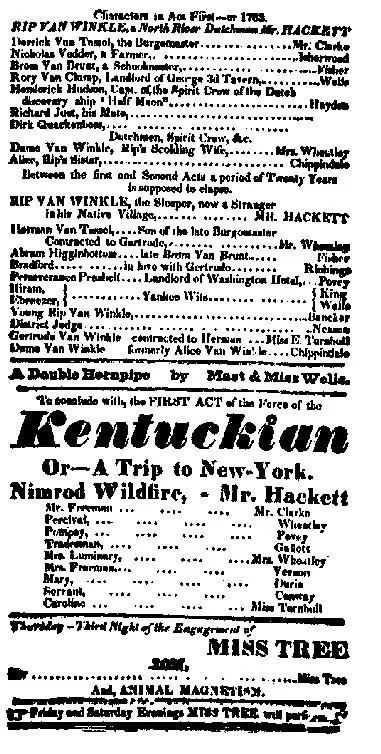

This incident undoubtedly whetted the interest of Joseph Jefferson, and he set about preparing his version. He had played in his half-brother's, and had probably seen Hackett in Kerr's. All that was needed, therefore, was to evolve something which would be more ideal, more ample in opportunity for the exercise of his particular type of genius. So he turned to the haven at all times of theatrical need, Dion Boucicault, and talked over with him the ideas that were fulminating in his brain. Clark Davis has pointed out that in the Jefferson “Rip” the credits should thus be measured:

Act I.—Burke + Jefferson + Boucicault ending.

Act II.—Jefferson.

Act III.—Burke + Jefferson + ending suggested by Shakespeare's “King Lear.”

But, however the credit is distributed, Jefferson alone made the play as it lives in the memories of those who saw it. It grew by what it fed on, by accretions of rich imagination. Often times, Jefferson was scored for his glorification of the drunkard. He and Boucicault were continually discussing how best to circumvent the disagreeable aspects of Rip's character. Even Winter and J. Rankin Towse are inclined to frown at the reprobate, especially by the side of Jefferson's interpretation of Bob Acres or of Caleb Plummer . There is no doubt that, in their collaboration, Boucicault and Jefferson had many arguments about “Rip.” Boucicault has left a record of the encounters:

“Let us return to 1865,” he wrote. “Jefferson was anxious to appear in London. All his pieces had been played there. The managers would not give him an appearance unless he could offer them a new play. He had a piece called ‘Rip Van Winkle’, but when submitted for their perusal, they rejected it. Still he was so desirous of playing Rip that I took down Washington Irving's story and read it over. It was hopelessly undramatic. ‘Joe’, I said, ‘this old sot is not a pleasant figure. He lacks romance. I dare say you made a fine sketch of the old beast, but there is no interest in him. He may be picturesque, but he is not dramatic. I would prefer to start him in a play as a young scamp, thoughtless, gay, just such a curly-head, good-humoured fellow as all the village girls would love, and the children and dogs would run after’. Jefferson threw up his hands in despair. It was totally opposed to his artistic preconception. But I insisted, and he reluctantly conceded. Well, I wrote the play as he plays it now. It was not much of a literary production, and it was with some apology that it was handed to him. He read it, and when he met me, I said: ‘It is a poor thing, Joe’. ‘Well’, he replied, ‘it is good enough for me’. It was produced. Three or four weeks afterward he called on me, and his first words were: ‘You were right about making Rip a young man. Now I could not conceive and play him in any other shape’.”

When finished, the manuscript was read to Ben Webster, the manager of the Haymarket Theatre, London, and to Charles Reade, the collaborator, with Boucicault, in so many plays. Then the company heard it, after which Jefferson proceeded to study it, literally living and breathing the part. Many are the humourous records of the play as preserved in the Jefferson “Autobiography” and in the three books on Jefferson by Winter Frances Wilson and Euphemia Jefferson.

On the evening of September 4, 1865, at the London Adelphi, the play was given. Accounts of current impressions are extant by Pascoe and Oxenford. It was not seen in New York until September 3, 1866, when it began a run at the Olympic, and it did not reach Boston until May 3, 1869. From the very first, it was destined to be Jefferson's most popular r�le. His royalties, as time progressed, were fabulous, or rather his profits, for actor, manager, and author were all rolled into one. He deserted a large repertory of parts as the years passed and his strength declined. But to the very end he never deserted Rip . At his death the play passed to his son, Thomas. The Jefferson version has been published with an interpretative introduction by him.

When it was first given, the play was scored for the apparent padding of the piece in order to keep Jefferson longer on the stage. The supernatural elements could not hoodwink the critics, but, as Jefferson added humanity to the part, and created a poetic, lovable character, the play was greatly strengthened. In fact Jefferson was the play. His was a classic embodiment, preserved in its essential details in contemporary criticism and vivid pictures.

[It is common knowledge that “Rip Van Winkle,” as a play, was a general mixture of several versions when it finally reached the hands of Joseph Jefferson. From Kerr to Burke, from Burke to Boucicault, from Boucicault to Jefferson was the progress. The changes made by Burke in the Kerr version are so interesting, and the similarities are so close, that the Editor has thought it might be useful to make an annotated comparison of the two. This has been done, with the result that the reader is given two plays in one. The title-page of the Kerr acting edition runs as follows: “Rip Van Winkle; A Legend of Sleepy Hollow. A Romantic Drama in Two Acts. Adapted from Washington Irving's Sketch-Book by John Kerr, Author of ‘Therese’, ‘Presumptive Guilt’, ‘Wandering Boys’, ‘Michael and Christine’, ‘Drench'd and Dried’, ‘Robert Bruce’, &c., &c. With Some Alterations, by Thomas Hailes Lacy. Theatrical Publisher. London.” The Burke version, used here as a basis, follows the acting text, without stage positions, published by Samuel French. An opera on the subject of “Rip Van Winkle,” the libretto written by Wainwright, was presented at Niblo's Garden, New York, by the Pyne and Harrison Troupe, Thursday, September 27, 1855. There was given, during the season of 1919–20, by the Chicago Opera Association, “Rip Van Winkle: A Folk Opera,” with music by Reginald de Kovan and libretto by Percy Mackaye, the score to be published by G. Schirmer. New York.]

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Representative Plays by American Dramatists: 1856-1911: Rip van» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.