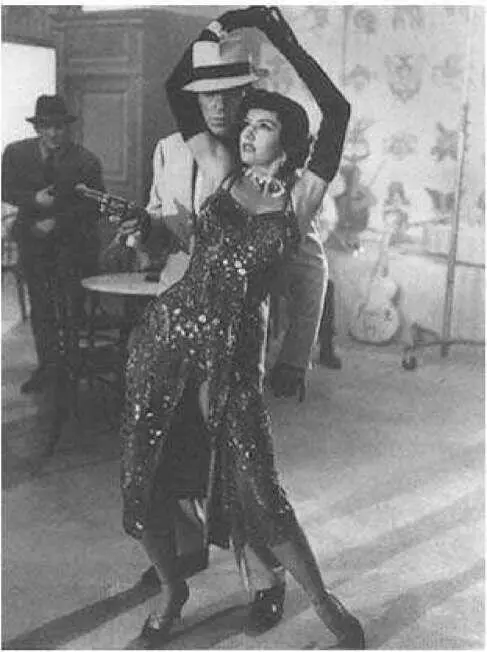

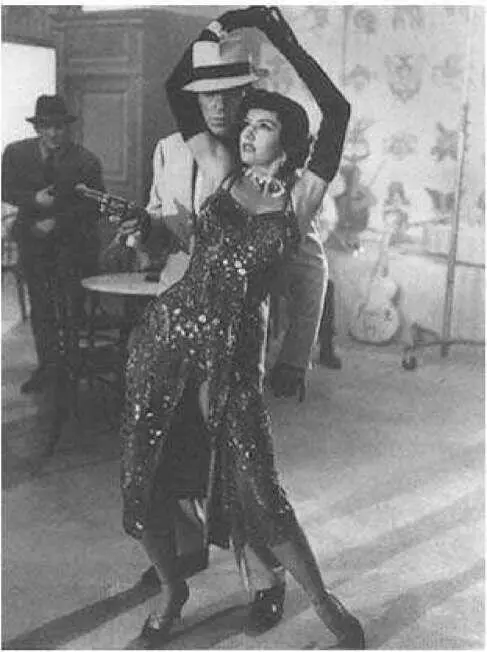

The "Girl Hunt" ballet in The Band Wagon (1953).

(Museum of Modern Art Stills Archive.)

For Borde and Chaumeton, "The Girl Hunt" captures the "very essence" of the noir series, submitting it to a "poetic transformation." Minnelli, they argue, is both a commercial surrealist and a "tortured aesthete," whose "lucid complicity" with the 1940s is made possible by the fact that noir itself had become little more than a "memory." The sumptuous ballet, they suggest, ought to be preserved in a kind of ''imaginary cinemateque," as a memorial to a dead form (138). The problem with such arguments, however, is that "The Girl Hunt" was nothing especially new. Minnelli had staged similar parodies in his Broadway revues of the 1930s, and one of the first pictures he wanted to make when he went to Paramount in 1937 was Times Square, a parodic "mystery chase" set to Broadway show tunes. He also knew the smash hit Guys and Dolls (1950), in which dapper gangster Sky Masterson sings "Luck Be a Lady," dressed in a costume similar to Astaire's in The Band Wagon. This and many other musical shows about the underworld were clearly an influence on "The Girl Hunt," which satirizes not only Hollywood but also the most successful American author of 1953, Mickey Spillane.

The example of Spillane helps to underscore the fact that showbusiness parody often has less to do with the ridicule of a dead style than with an attempt to capitalize on a wildly popular trend. Consider the many cartoon parodies released by Warner Brothers in the 1940s and 1950s. One of these is a Fritz Freeling production of 1944, involving a wolf in a zoot suit who visits a theater to see To Have and Have Not. (The Zoot Suit riots in Los Angeles had occurred only a year earlier.) The cartoon itself is in Technicolor, but what the wolf sees is a perfectly executed black-and-white caricature, filled with absurdly comic exaggerationsas when Bogart lights Lauren Bacall's cigarette with a blowtorch. A later Warner cartoon by Chuck Jones, timed to coincide with the studio's release of Dragnet (1954), casts Porky Pig and Daffy Duck as Sergeants Joe Monday and Shmoe Tuesday, who work as cops on a futuristic space station. The cartoon imitates Jack Webb's popular TV show, but at the same time it resembles an old-style film noir, with Porky and Daffy talking around the cigarettes in their mouths.

A similar desire to ape current fashions lies behind films such as Fatal Instinct, which was designed to satirize not only the classics of the 1940s, but also Body Heat, Fatal Attraction, Cape Fear, and Basic Instinct. Much the same thing could be said about Carl Reiner's more effective and technically brilliant parody, Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid (1982), which was made possible by the fact that vintage films noirs still circulate as commodities on TV. In other words, even when parody ridicules a style, it feeds on what it imitates. I would go further: much like analytic criticism, parody helps to define and even create certain styles, giving them visibility and status. "We murder to dissect," William Wordsworth once said of critics, and parodists could be charged with a similar crime; but scholars and mimics also preserve what they destroy, transforming it into an idea that can be revived by later artists. (This would explain why a series of film-noir burlesques, including The Black Bird [1975] and The Cheap Detective [1978], were roughly contemporary with the rise of neo-noir.)

It seems obvious that both parody and criticism have helped to shape the popular conception of film noir, enhancing its strength as an intellectual fashion and as a commercial product. Even so, we cannot say exactly when parodies of noir began, and we cannot distinguish precisely between parody, pastiche, and "normal" textuality. Samuel Goldwyn's They've Got Me Covered (1944), starring Bob Hope, contains at least one sequence (photographed by noir cameraman Rudolph Mate) that mimics all the visual conventions of the dark thrillers of its day. A later Hope film, Paramount's My Favorite Brunette (1947), features Alan Ladd in a cameo appearance as a tough private eye. Are these parodies, or clever tributes? Notice also that both Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler occasionally wrote subtle burlesques of their own fiction. Frank MacShane argues that Chandler was a comic novelist and that at least one of his stories, "Pearls Are a Nuisance" (published in Dime Detective in 1939), is a "parody from start to finish" (Life of Raymond Chandler, 56). According to MacShane, some of the more flamboyant aspects of Chandler's prose, such as his description of a violent beating in "Bay City Blues'' and his famous opening to "Red Wind" ("On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands' necks. Anything can happen. You can even get a full glass of beer at a cocktail lounge."), were intended to suggest that "much of what he was writing was rubbish" (Life of Raymond Chandler , 5657). 34

Even a classic film noir like Out of the Past derives much of its charmat least for contemporary viewersfrom the fact that it verges on self-parody (a quality it shares with The Lady from Shanghai, which was released in the same year). The basic ingredients are almost too familiar: a trenchcoated, chain-smoking private eye; a gorgeous femme fatale; a flashback narrative; a world-weary, first-person narration telling a story of murder, betrayal, and sexual obsession; a downbeat ending; and a haunting theme song played not only by the studio orchestra but also by every jazz band and barroom pianist in sight. (This same tune had been used in Crack-Up, another film noir produced at RKO in the previous year.) The plot, derived from Daniel Mainwaring's Build My Gallows High, is strongly influenced by The Maltese Falcon, and the dialogue (the best of it written by the uncredited Frank Fenton) is rich with quasi-Chandleresque wit. Some of the lines could have been used for all intentional parody like "The Girl Hunt." At one point, for example, the good girl (Virginia Huston) remarks that Jane Greer "can't be all badnobody is." Mitchum wryly mutters, "She comes the closest." Mitchum's offscreen narration has a similar quality. "I never saw her in the daytime," he says of Greer. "We seemed to live by night. What was left of the day went away like a pack of cigarettes you smoked.'' All the while, the film as a whole seems intelligently self-reflexive or artful in the way it treats its secondhand atmospherics. When we hear the lines I have just quoted, we see the private eye seated at an outdoor café in a Mexican plaza at dusk, directly across from a neon-lit theater called the "Cine Pico," which is showing Hollywood movies. From this very spot, the belle dame sans merci makes her mysterious entrance, like a creature of the pop-culture imagination.

The European auteurs of the 1960s and 1970s, who helped create the idea of film noir, were even more self-conscious than a director like Jacques Tourneur; they grounded their work in allusion and hypertextuality rather than in a straightforward attempt to keep a formula alive. Godard and Rainer Fassbinder were especially notable for the way they eschewed melodramatic plots and realistic sex and violence, reducing the private eye and the gangster to comic-book stereotypes (sometimes, as in Breathless and The American Soldier, via characters who imagined themselves as heroes but were actually playing stereotypical roles). Even Truffaut's more lyrical Shoot the Piano Player keeps the old conventions at a playful distance: when Charles Aznavour and Marie Dubois walk down the Paris streets in trenchcoats, the effect is vaguely comic, as if they were on their way to a costume party. The German Wire Wenders, who began his career as an avant-garde artist, and who briefly became a sort of crossover phenomenon, took a somber approach. His most commercially successful film, The American Friend (1977), is a loose adaptation of a Patricia Highsmith novel, written half in English and half in German, which can be read as a straight thriller modeled on Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray, as a pastiche of certain Hollywood conventions, and as an allegory about the relationship between America and West Germany two generations after World War II. Here and elsewhere, the idea of film noir tends to bridge a gap between Europe and America, between mainstream entertainment and the art cinema. Thus American film noir of the "historical" period was largely a product of ideas and talent appropriated from Europe, and neo-noir emerged during a renaissance of the European art film, when America was relatively open to imported culture. The second of these two phases was affected not only by the French and German New Waves, but also by an Italian tradition of philosophical noiras in Antonioni's pop-art Blowup and Bertolucci's retro-styled The Conformist (1971). It was also strongly influenced by European directors who made English-language thrillers that were aimed partly at the American market: not only Antonioni, but also Polanski (Repulsion), Boorman (Point Blank), and eventually even Wenders (Hammett).

Читать дальше