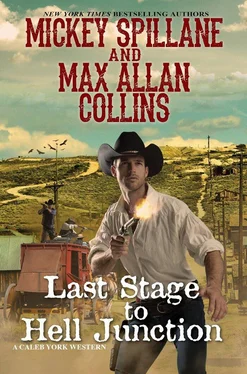

“Yes,” the Filley woman said, nodding. Her eyes again sought Willa. “Your father was against it, I understand. He was a lovely man, they say, one of the founders of the town. But you seem forward-looking enough to see the future can’t be avoided.”

Willa smiled a little. “Mr. Parker is funding the train station that will be built in Trinidad.”

“On land that your father left to Caleb York.”

Willa swallowed. “That’s right.”

“The station will be named after your father, I hear.”

“That’s correct.”

The saloon woman’s head tilted and she frowned just a touch. “I wonder if he would appreciate that, as strongly opposed as he was to the railroad coming in.”

Parker, perhaps sensing an undercurrent of tension between the women, said, “I think George would in time have come around. I believe Willa would have made him see the sense of it. And I would have been at her side, helping convince him.”

The Filley woman smiled and said, “I’m sure you’re right. Of course, we’ll never know.”

Willa thought that deserved a sharp reply, but before she could summon one, Bratcher’s “Yahhh! Yahhh!” came from above, announcing their departure, mingled with the jangle of reins and the building clop of the horses’ hooves, the wooden wheels turning and cut by the occasional whinny. Citizens on the boardwalk, especially children, waved and hollered. A stagecoach leaving town, even after all these years, was still something to see — including a smaller coach like this one, with just four horses.

The Filley woman again addressed Parker. “Are you a lawyer as well as a businessman, sir?”

“Why, no. Why would you think that?”

She shrugged. “Sounds like you’re representing Miss Cullen in the Santa Fe matter.”

They were outside town now, stirring dust on the narrow road through nothing much. The stagecoach’s continuous motion had them swaying already, with hanging leather straps to provide support if need be.

“I’m providing her with an attorney,” Parker said, just a bit stiffly, “with whom I regularly do business. And as her father’s onetime partner, I’m here to advise and help in any way I can. It’s a privilege of age.”

The saloon woman smiled. “You don’t look particularly aged to me, Mr. Parker. Are you a married man?”

The question surprised him. “I was. I’m a widower.”

“I’m sorry for your loss. Is it a recent one?”

“No. Over ten years past.”

“And you’ve never re-married?”

“I never found the right... one.”

“Well, you know what they say.”

Willa asked, “What do they say, Miss Filley?”

Her smile was pursed, as if she were about to blow a kiss. “It’s never too late.”

The road out of Trinidad was rutted and narrow through a flat expanse broken at left by the burnt-red buttes along the horizon, their scarred black cliffs the work of rain and wind. Off to the right were the hills that grew into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and their canyons, one of which fed the Purgatory River, so vital to Trinidad.

An awkward silence had followed the Filley woman’s last remark, and finally Parker broke it, saying, “We’re riding into history, you know.”

Both women looked at him curiously.

He said, “Rides like this will be confined to memory, before long. When the railroad comes in, there’ll be no need for a stage line between Las Vegas and Trinidad. Little or no need in the Southwest for any stages at all. Change is of course inevitable, but I feel somewhat sad about it.”

Willa asked, “Why is that, Mr. Parker?”

“Please call me Raymond. Both of you ladies. The West is changing. Trinidad is changing. They have telephones in Tombstone, you know.”

The Filley woman nodded. “I’ve heard that.”

“Don’t take me wrong, Miss Cullen, Miss Filley.”

Neither took the opportunity to suggest he use their first names.

“I approve of change,” he said. “I seek it out. But not without an awareness that something has been lost. That as we become more civilized, with a new century ahead, a way of life will soon fade from view.”

The Filley woman, frowning in thought, asked, “Is that a bad thing?”

“Not bad or good. Just reality.”

The coach began to come to a jerky stop. The three passengers, surprised and somewhat alarmed, were jostled fairly hard by it.

Parker leaned out his window, then said to the women, “There’s a young man in the road, waving us down. Appears to be in trouble...”

Willa leaned out her window. Just up ahead, off to the right, was Boot Hill, the name reflecting tradition and not landscape, as it was as flat as the rest of the dusty ground. The difference was a massive mesquite tree that made for shade and provided color enough to make a suitable home for the nest of wooden crosses and the occasional tombstone.

Right now the cemetery was fairly obscured by the dust the stopping stage had stirred.

Up top, Norval Bratcher was calling out, “Ye need a ride, son?”

“Be obliged,” the young man said. “Iffen you can’t take me back to Trinidad, might be I could tag along to the Brentwood crossroads.”

Willa, leaning out, could see the slender male form in his ready-made gray shirt with arm garters and tight-waisted, loose-legged California pants of buckskin-color wool. He was clean-shaven and generally clean-looking with a big smile and friendly eyes, his blond hair short. He wore no gun belt as he moved easily, steadily toward the stage.

“Son,” Bratcher’s voice came, “we can’t rightly head back.”

The Filley woman said to Parker, “It’s only half a mile. Surely we can—”

“Don’t mean to trouble you none,” the young man said, very near the coach now. He gestured back behind him. “My horse busted a leg and I had to put her out of her misery. Maybe they’ll sell me a new ride at the relay station.”

“Worth a try,” Bratcher said. “Gus, help him up.”

Parker leaned out and said, “The boy can ride with us.”

“Sorry, Mr. Parker,” Bratcher called down. “Company policy. He comes up top.”

The stage swayed a bit as the new passenger was hauled up onto the seat. As that was happening, a trio of horsemen rode out from behind Boot Hill’s mesquite and closed the short distance between the cemetery and the stopped coach, raising a small dust cloud. In seconds, they were three abreast, stretched out in front of the Concord, raising guns that were already drawn.

“The Hargrave bunch,” Parker whispered harshly.

Willa had heard of them. Everyone in this part of the West had — led by the notorious Blaine Hargrave, they had robbed trains, banks, and, yes, stages.

“I saw him play Hamlet,” Willa breathed, her heart beating fast.

Hargrave was an actor who’d come west from New York, traveling with his own company in the manner of Edwin Booth and Lotta Crabtree. But after he murdered a heckler in Virginia City, leaving without a curtain call, the next show he put on was a stagecoach robbery.

Was this an encore?

She looked out at the three men, recognizing Hargrave, all in black like Caleb — coat, vest, pants, boots, only his black hat was a flat-crown plantation number, and his shirt was white and ruffled, open at the neck to reveal a nest of hairy black, his well-carved, handsome face sporting a black mustache suiting his current role as villain, not hero.

Hargrave was center stage, of course. On his either side were the spear carriers — well, revolver carriers in this instance: a blue-army-shirt-clad man of thirty-some who resembled the boy who’d flagged them down (an older brother?) and a burly, bearded character in a plaid jacket who might have been a miner, though one who’d traded in his pickax for a revolver.

Читать дальше

![Микки Спиллейн - Death of the Too-Cute Prostitute [= Man Alone]](/books/437201/mikki-spillejn-death-of-the-too-thumb.webp)