The supposed salesman almost yelled as he said, “Anybody else here see it different?”

If anyone had, they were keeping it to themselves.

“The circuit judge will be through here next week,” York said, hand still on the butt of his holstered gun, finger slipping onto the trigger. “May be that a witness or two will testify in your defense. Maybe others will have their own story to tell. Until then, you’ll be my guest.”

Crawley smiled, the slight mustache emphasizing it. “Not damn likely,” he said.

“You know who I am?”

“I do. You’re Caleb York. And I’ll warrant you’re faster than me. But my gun is already out.”

With a tilt of his holstered gun, York fired, blowing a hole in the toe of the gunny’s boot. The wounded man howled and did another dance, even more awkward than before, as York slapped the .45 from his hand.

Between moans and whimpers and yelps, the gunny cursed York with obscenities, the like and variety of which were rarely heard even in a saloon.

York slapped him. “You’re in mixed company.”

Crawley lost his balance and fell hard, rattling the dance floor, winding up beside the man he’d shot, getting soaked some in the blood he’d spilled.

“Bastard!” he swore up at York.

York kicked him in the side and said, “Some of you boys sit him in a chair.”

A couple of cowhands did that while York collected the .45 he’d slapped away. At least that hadn’t gone off. Doc was already over, kneeling at the gunfighter’s feet, lifting the left one to remove the shot-up boot and reveal a blood-soaked stocking and a mess of gore where a couple of toes should be.

York checked on Molly, who Rita was already comforting at a table well away from the dance floor. Tulley appeared at his side, looking eager as a puppy after a bone.

“Need me, Sheriff?”

“Questionable, your timing.”

“Well, ye seemed to be runnin’ the show.”

“When Doc’s through with that rabble, get a couple of these cowboys to help you haul him over to the jail.”

Tulley nodded and scurried off to recruit some help.

York returned to the poker table and the little group resumed play, minus the doc. The sheriff had won two hands and lost one when Doc Miller came over, not to rejoin the play but to report on his new patient.

Leaning in, Miller said, “He lost two toes, but he’ll live. Won’t never dance worth a damn again.”

“He didn’t dance worth a damn before. Tulley and some fellas are going to haul him over to the jail. Finish anything up that needs it over there, would you?”

Doc went off to do that.

“Now,” York said, “maybe we can play cards.”

Two hours and a few minutes later, York — having won almost one hundred dollars from the city fathers — stopped by the jail to see how Tulley and the prisoner were doing. Since Doc Miller had returned to the game half an hour before, York already had a pretty good idea the prisoner was well in hand.

Tulley was at his little scarred-up table with a wall of wanted posters behind him, wood crackling in the potbelly stove nearby. He was having some of his own coffee now, which was a comedown from the Victory.

“Our guest sleeping?” York asked.

Tulley shook his head. “Jest listen fer yerself — he’s a moanin’ and a groanin’. But I don’t think he’s feelin’ much pain.”

“Then why is he moaning and groaning?”

Tulley grinned; it was a yellow thing but had more teeth in it than you might expect. “Go on back ’n’ see. But he’s a mite discombobulated on laudanum that the doc done give him.”

York shrugged and headed back into the little cell block.

Crawley was on his back on the chain-slung cot against the cell’s rear wall. His britches were off, and his long johns were tugged up around his left ankle, the toe area of his left foot bandaged, red coming through. Seeing York through the bars, Crawley sat up.

“ Sheriff! Sheriff, we have to... have to work this thing out!”

“We will work it out just fine. Like I said, the circuit court judge will—”

Crawley actually got himself off the cot and hopped and hobbled over, cringing when he put any weight on the left foot, but then he was holding onto the bars right in front of York, his face contorted. He looked like a kid about to cry.

“I got to be on the morning stage! People are countin’ on me. Already bought my ticket this afternoon! You check my things that chumpy deputy of yours took offa me and see if I didn’t. What I got to do is damn important!”

“You killed a man, Mr. Crawley. That’s damn important.”

He was shaking his head, face contorted with worry. “You don’t understand, York. I got someplace to be , and it sure as hell ain’t Trinidad.”

“That kid you killed isn’t going anywhere, and neither are you.”

The prisoner pressed his face between the bars and whispered, “Look, man. I told that Wiggins feller at the livery stable he can have my horse for two hundred dollars.”

“That’s a lot of horse flesh.”

“We’re talking about a cavalry-type horse, Sheriff, fifteen hands, a thousand pounds, five years old, well-broken. You can have it yourself, or take the dollars!”

“Does sound like the horse is worth that much.”

“It is! It is!”

“That boy’s life was worth more.”

And the sheriff left the killer there to rattle the bars until all that was left for him to do was to hobble back to his bunk.

But Caleb York couldn’t help but wonder...

... what was so important about taking the morning stage?

That Caleb York had come to see the stage off pleased Willa Cullen no end.

The twenty-three-year-old young woman sported a brand-new, catalogue-ordered, dark-blue dress with a gathered waist and white lace trim at the neckline and elbow-length sleeves — with a matching jacket to take the edge off a chilly February morning.

Yellow hair braided up in back, she was a tallish Viking of a girl with an hourglass figure, who — despite delicately pretty features and long-lashed, cornflower-blue eyes — looked just about perfect for childbearing or helping with crops. But she was not married and her ranch — and it was her ranch now, since her father’s death a month ago — was strictly cattle. That spread, the Bar-O, was the biggest in the surrounding area.

She had watched as heavy-set, bristle-bearded Gus Gullett, the shotgun guard, had loaded her luggage up into the boot at the rear of the stage. Then when she turned back toward the hotel, where out front the stage was waiting for its passengers, she’d drawn in an unbidden breath upon seeing the sheriff on the boardwalk above. Though it was only a handful of steps up from the street, he fairly loomed.

She felt irritated at herself for that giddy girlish reaction.

Yet could any woman blame her? Caleb York stood tall, broad-shouldered but lean, his jaw near jutting, his temples touched with gray but his hair, including that close-trimmed beard he’d taken to wearing of late, was otherwise a rich reddish brown. His face was a contradictory thing, sharp bones home to pleasant, even easygoing features, his eyes as light blue as denim that had seen too many washdays.

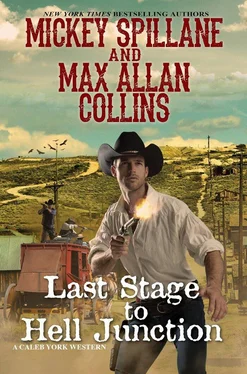

Caleb’s general appearance was contradictory as well. That low-slung revolver, tied down on his thigh, said gunfighter; but his black attire — hat and coat and cotton pants and boots — said professional man. Going on a year ago, when Caleb York rode into town a nameless stranger, many had taken him for a dude. Men beaten senseless and others who fell dead under his gunfire learned otherwise.

Events had stranded Caleb, who’d been on his way to San Diego and a job with Pinkerton’s, and during his unintended stay, Willa and Caleb had become something of a... couple. She’d been well aware he had taken on the sheriff’s job “only temporary” — the position had been vacated when its previous corrupt occupant had become one of those men who fell under Caleb’s gunfire. Yet the rancher’s daughter felt they’d grown close enough for him to change his mind and stay around.

Читать дальше

![Микки Спиллейн - Death of the Too-Cute Prostitute [= Man Alone]](/books/437201/mikki-spillejn-death-of-the-too-thumb.webp)