Although it is widely assumed that Ruud is more effective in midfield, his first awards came as a result of his superb displays as a sweeper. Mirror Sport readers voted him the FA Premier Leagueâs Most Valuable Player of the Month for September 1995. He was also the first McDonaldâs/Shoot Player of the Month, averaging 8.25 ratings for his performances, including five man-of-the-match nominations in his first eight games. Shoot said: âHe was awarded a mark of nine out of ten in four of those great games and was head and shoulders above the rest of the Premiership stars.â

But you will never meet a more modest chap. When he was awarded the Evening Standardâs Player of the Month award for January 1996 â as an outstanding midfield player â the newspaperâs chief football correspondent Michael Hart, hardened by years in the cynical world of this particular tainted sport, was almost shocked by Gullitâs reaction. He wrote: âYou would think that someone who has touched the heights of the world game might not rank winning the Evening Standard Footballer of the Month award too highly among the golden moments of an epic career. Yet Ruud Gullit turned out to be one of the most gracious recipients of the last quarter of a century. Not just gracious, but genuinely grateful. âI couldnât have won this without the rest of the team,â he said. âThey make a lot of jokes about me in the dressing room but Iâm very happy with the guys.â To prove the point, he insisted on including the rest of the Chelsea team in the photograph and publicly thanked his colleagues who have come to appreciate the enduring influence of one of the worldâs great players. âThe first thing you want is that the team plays well,â said Gullit. âA team is like a clock. If you take one piece out, it doesnât workâ.â

Gullit became a born-again player in his first year at Chelsea. âI seem to have gone back in time. Iâm playing like itâs the beginning of my career again and that Iâm an 18-year-old again. The child in me can play on because I am still enjoying it, and if I enjoy it I can express myself better.â He also much prefers the attacking style of play over here compared to the often negative attitude back in Italy. âIn England you donât just stay back and defend,â he says. âYou are not a slave to tactics and results.â

To watch Gullitâs long-range passing is a delight. It used to be the hallmark of Hoddle himself, but somehow Gullit has a far greater degree of consistency in his passing. That is what should be meant by the long ball, instead of the kick and rush, or kick and hope. Gullit plays the short passes with carefree simplicity and the long-range missiles with uncanny accuracy. As Michael Hart wrote: âGullitâs job, wherever he plays, is quite simple. His presence, his ability on the ball, his vast stride, his vision, his range of passing ⦠all were essential to Hoddleâs doctrine. With Gullit in the side the Chelsea players had the conviction they needed to successfully interpret Hoddleâs tactics.â

A huge debate erupted during the course of the 1994/95 season over the value of imported stars, their quality and the influx as a result of the Bosman case. Gordon Taylor, of the Professional Footballers Association, was at the sharp end of the controversy with work permit problems involving Romanian World Cup star Ilie Dumitrescu. While Taylor is a concerned Euro-sceptic, he welcomed Klinsmann and laid down the red carpet for players like Gullit, Ginola, and Bergkamp. Their arrival, he believed, far from diminishing opportunities for home players that might be the case with the also-rans that join the influx, can stimulate young playersâ development. Taylor, nevertheless, insisted that while transfer turnover had reached £130 million a year, the proportion of it going to clubs in the lower divisions was falling.

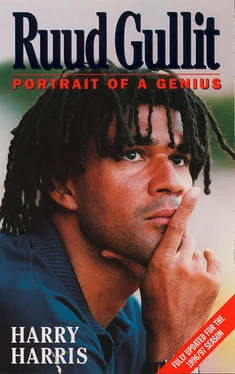

The desirability of a large number of foreign players was in question. But players of the highest quality can only enhance the English game and they donât come any higher than Ruud. As Stan Hey wrote in the Independent on Sunday: âGullit, whose magnificent physique and twirling dreadlocks are dramatic enough prologues even before he touches a ball, is probably the most prestigious import to the English game since Osvaldo Ardiles arrived at Tottenham with his World Cup winnersâ medal.â

The acquisition of Gullit was so natural for Hoddle after his decision to finally end his own illustrious playing career. Hoddle began his three-year stint as a player-manager at the Bridge in the sweeper role. He believed he had found the perfect player to fill the void. Hoddle, explaining the original concept for signing Gullit, said: âI earmarked him three months before the end of the 1994/95 season when I was looking for a sweeper. The big question was whether we could get him. I thought at first it would be a struggle to afford him. Then, when I discovered he was on a free transfer, I couldnât believe it. It proved to be a long, hard struggle to sign him, but I was convinced it was going to be a worthwhile struggle.â

Gullitâs pre-requisite for any move from Italian football was the freedom to fulfil his desire to return to playing in a sweeper system. He was determined to make it work. But he equally accepted without complaint a switch to midfield where he became the cornerstone of Chelseaâs transformation. Gullit was prepared to forsake his desire to play sweeper because of his respect and affection for Hoddle. Equally, Hoddle was ready to ditch his original conception of Gullitâs role for the overall benefit of the team, yet still retain his philosophy of playing three at the back with David Lee taking over as the sweeper.

Right from the outset Gullit had an affinity with Hoddle as he explained at the start of the 1995/96 season: âI like the way Glenn thinks about football. The reason I came to Chelsea is that it is one of the English clubs managed by an English player who has played abroad. Glenn Hoddle, like Kevin Keegan, wants more than just kick-and-rush football. Because if you keep possession of the ball, you can dictate the game, and wait for the right moment to attack. Most of the Premiership teams play more on the ball now, which is one of the reasons the rest of Europe has become so positive about the English game. If we have the ball, we can play to our own rhythm, rather than allow our opponents to play the ball at high speed. If you always have the ball, you can direct the game.â

It only took a few games for Gullit to appreciate that his sweeper role in English football would not be permanent. Gullit was never going to be dictatorial about his role as he explained from the very outset: âIn my career, coaches and managers have always tried to play me in different positions. I happen to be a player who can play in almost every position. Sometimes thatâs a bonus, sometimes it can be a disadvantage. I can say I claim the sweeper position for the entire season, but if we get problems up front I might be asked to go and play there.

âWhen I started playing as a kid it was as a libero because I was big and kicked very hard,â he said. âI played there when I turned professional, but my club always needed someone strong up front. I went up front, made a lot of goals, which was my fault,â he joked. âThen they needed someone on the right wing. I did well on the right wing, then PSV wanted me as a libero and I did well there. Then they needed someone up front, so I played up front and made goals â and so it has carried on.â

Ruud absorbs a great deal of information and has a wide range of interests. Unlike the archetypal footballer whiling away those hours of free time watching football videos, drinking, betting or going to the dogs, Gullit has been hooked by the wide range of documentary programmes on television. After the second home match of the season, a thrilling, if disappointing 2â2 draw with Coventry, Gullit sat in the near deserted Bridge press room close to the dressing rooms discussing philosophy with a handful of journalists who could be bothered to wait until he had conducted an assortment of television and radio interviews. With a twelve-day break before the next match because of international games, Gullit was asked if he would indulge in catching up with English football by watching videos of matches. Not at all. Instead, he would continue his television diet of serious programmes. He said: âI watch football on TV but not all the time. There are a lot more important things to see. Certain things are fascinating. One was about Siamese twins, and how the surgeons decided to separate them. One of the girls survives but misses her sister and even names her false leg after her twin. That touches you. You see what the children have to endure. You see the problems of autistic children and imagine how the parents have to live with it. Your whole life can be occupied by the plight of children. You see how lucky you are.

Читать дальше