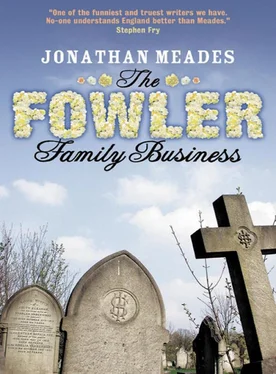

The Fowler Family Business

Jonathan Meades

Dedication Dedication Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-One About the Author Other Works Copyright About the Publisher

For: H, R, L, C – and C

Cover

Title Page The Fowler Family Business Jonathan Meades

Dedication Dedication Dedication Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-One About the Author Other Works Copyright About the Publisher For: H, R, L, C – and C

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

About the Author

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

Once it had been Henry and Stanley, Stanley and Henry. Stanley was the card, not Henry. Stanley was a caution, Henry wasn’t, Henry was cautious. Stanley was his da’s boy – all chat, and then some, such a tongue in his mouth. Henry’s tongue was fixed in the prison of his teeth whose incisor accretions, plaque, molar holes and food coves were his friendly familiars. You chum up with those ravines and contours if you’re tongue-tied. You go in for interior potholing. You have friends inside, three dozen of them, each with its tidemark of salts from forgotten meals, from grazes taken with Stanley, from wads shared on the way to school, from midnight feasts when they stayed over at each other’s.

It was always Henry and Stanley. Stanley was such a one. It was always the two of them together, Stanley taking the lead, Henry gingering along behind whilst Stanley got into scrapes and scrumped and larked about and scaled the old Victoria plum tree which Mr Fowler called ‘Her Majesty’. Mr Fowler watched in trepidation as Henry clambered about the lower boughs (Stanley was already at the top, his head poking through the leaves). He feared that his precious son might tumble and crack his crown and so be taken from him and Mrs Fowler – though, heaven knows, it was Stanley’s da who had more cause to harbour such a fear for he and Mrs Croney had lost an infant girl to diphtheria the winter before the war ended. Stanley was the hasty replacement, born less than a year after Wendy, poor mite, had perished.

Mr and Mrs Fowler were paranoiacally protective of Henry who reciprocated with a dutiful obedience which masked his timidity: he never ventured out of his depth, he never ran across the road, he was a responsible cyclist. Henry was irreplaceable.

In their family they were, all three of them, fans of Charlie Drake, the squeaky knockabout comic. Knockabout! He surely put himself through it. His weekly television show was a self-inflicted assault course. They howled with laughter in the curtained room lit by cathode blue. Mr Fowler with his Saturday bottle of Bass, Mrs Fowler with her fifty-two-weeks-a-year Christmas knitting, Henry in his raglan and pressed flannels, the three of them wondering what the irrepressible little trouper would get up to next. He tumbled, our Charlie fell. He crashed through walls. He went A over T into porridge vats. He’d better watch out for himself – Mr Fowler said as much. ‘Ooh he’s going to come a cropper Mother!’

Then he added, he always added, he put down his tankard and added gravely: ‘Don’t ever – don’t you ever – you listening Henry my boy – don’t you ever think of trying that. Don’t you ever.’

Pearl one, stitch one, take one in. ‘And don’t,’ Mrs Fowler joined in, ‘ever do what Stanley was doing up Her Majesty either. I don’t know …’

Henry Fowler didn’t require such warnings. He was a watcher. He anticipated the worst. He observed Stanley’s clinging limbs as he did Charlie Drake’s flying ones. He observed them with contained blood-lust – the ability to put the limbs together again, nicely, for the relatives, was, after all, the family trade. When Charlie Drake crashed about Henry rocked to and fro on the settee, with his tongue in his teeth, rooting out the rotten holes, laughing with his mouth shut. He got eager, he got agitated. He willed injury on Charlie who lived nearby in Lawrie Park Road – he dreamed of being the one who would make Charlie, our Charlie, look more like Charlie, in death, than he had ever looked in life, so like Charlie that his kith’n’kin would hardly notice he’d passed over. He wanted Charlie to hurt himself that badly so that he might practise the trade passed down to him by his father and his father’s father who had founded the business in 1901 when he was just a young undertaker and Her Majesty the Queen and Empress Victoria had only lately died. He dreamed too that Stanley might one day be thrown from weak, ungrippable branches by a high gust and so leave the tree for the ground. The sky would be dazzling lactic grey.

Stanley was his friend, he was such a friend he was a brother – he implored his parents to give him a real brother but they disobliged. Stanley was so much a brother he loved him, he loved him so much that he wanted to break him, the way that adored toys are dismembered. They put toy boxes beneath the carpet in Henry’s bedroom to simulate B- Western canyons. The Sioux would ambush the cowboys. The transgressors, defeated, would be beheaded by Henry’s fretsaw. When the change from lead to plastic models was made, towards the end of their Indian wars, a penknife sufficed. After he had cut the head off Henry always wanted to reattach it, he always regretted what he had done.

Head wounds were Mr Fowler’s speciality. He had the good fortune to work in the golden age of head wounds. Health and Safety legislation was something he gloried in as an employer. He was a grateful beneficiary of its loopholes and of the laxity of its implementation. He had followed a war, in the company of an army padre, burying the still helmeted at Arromanches, in a wood near Rouen where ‘the chalk was like concrete’, and all around Caen (‘Canadian lads – hardly got their bum-fluff some of ’em’). In that war he had risen to sergeant-major, and after it he had dropped the sergeant part. And after it, too, he had revelled in the automotive potency of the age. Cars might not have been as routinely quick as they are today but they still got up a fair lick on roads that were built for old legions, horses, first-generation internal combustion. He had served in a war for his King and he believed from the very bottom of his still undicky ticker that mortal risk was the prerogative of everyone – save Henry, who was precious and irreplaceable.

Mr Fowler was happiest with A-roads, with arterial roads with central flower displays. He loved road-houses which men drove to with their bit on the side to get tight in, to adulterate marriage in a private room secured with a wink and a tip, to drink more after, to exit into the path of an oncoming vehicle. The metalled pelt of roads outside road-houses was frosted in winter, soft in summer (the season of minor mirages). The whole year through it was constellated with the evidence: red glass, rubber, chromium, cloth, Naugahyde, oil, body tissue, blood, especially blood. Every road-house had a bloody road in front of it. There were deaths galore. Racing drivers set an example to the male nation. They led short fast lives: Collins, Hawthorn, Lewis-Evans, Scott-Brown with his two names and one arm. They expected nothing more. In their mortal insouciance and dashing dress they aped The Few. They drove to die in flames and glory. After them young death would be delivered by the pharmacopoeia: no head wounds there.

Читать дальше