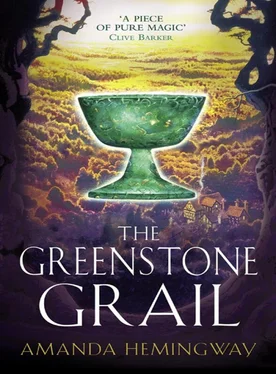

SANGREAL TRILOGY

Amanda Hemingway

Cover

Title Page SANGREAL TRILOGY

The Grail The Grail This is the cup the devil made to hold the lifeblood of a god , the cup from which the phantoms sprang that followed where his story trod . They wrought it in the Underworld – an older world, a younger day – before the God of Gods was born and angels stole the book away . They filled it with eternal life , undying death, unsleeping dreams; its draught unsealed the shadow-gate between the World that Is, and Seems . This is the cup to loose the soul , the blood that sets the legends free , and we who dare to drink must taste , each in ourselves, eternity .

Prologue: The Chapel

Chapter One: The Fugitives

Chapter Two: Dreams and Whispers

Chapter Three: The Luck of the Thorns

Chapter Four: The Pursuers

Chapter Five: The Man on the Beach

Chapter Six: Iron and Water

Chapter Seven: An Inspector Calls

Chapter Eight: Sing a Song of Sixpence

Chapter Nine: Sturm und Drang

Chapter Ten: On Robbery and Murder

Chapter Eleven: The Grail Quest

Chapter Twelve: Bluebeard’s Chamber

Epilogue: Afterthoughts

About the Author

Other Works

Copyright

About the Publisher

This is the cup the devil made to hold the lifeblood of a god , the cup from which the phantoms sprang that followed where his story trod .

They wrought it in the Underworld – an older world, a younger day – before the God of Gods was born and angels stole the book away .

They filled it with eternal life , undying death, unsleeping dreams; its draught unsealed the shadow-gate between the World that Is, and Seems .

This is the cup to loose the soul , the blood that sets the legends free , and we who dare to drink must taste , each in ourselves, eternity .

There were three things moving through the wood that evening: the boy, the dog, and the sun.

The slope faced north-west and as the cloud-shadow retreated the sun’s rays advanced through the trees on a collision course with the two companions, who were descending on a more or less diagonal route towards the light. The boy was dark, too dark for the Anglo-Saxon races, his skin a golden olive, his hair so black that there were glints of blue and green in it, and green and blue flecked the blackness of his eyes. His face was bony for his twelve years, a strange, solemn, mature face for someone so young. The dog was a shaggy mongrel, long-legged and wayward of tail, gambolling beside his friend with one ear pricked and the other lopped, his brown eyes very intelligent under whiskery eyebrows. He was known as Hoover from his habit of mopping up crumbs, though it was not really his name. The boy was called Nathan, and that was his name, at least for the moment. He had spent much of his short life exploring the woods, and around Thornyhill Manor he knew every tree, but here in this folded valley was the Darkwood where no paths ran, and he could never remember his way from one visit to the next. He sometimes fancied the trees shifted, rustling their roots in the leaf-mould, and even the streamlet which gurgled along the valley bottom would play curious tricks, switching its course from time to time as such little streams do, but without the excuse of sudden rain. It was very quiet there: few birds lived in the Darkwood. All this land had once been the property of the Thorn family (spelt Thawn in some of his uncle’s ancient books), and they had built a chapel down in the coomb, in the long ago days of chivalry and legend before history tidied things up. It had been struck by lightning or otherwise destroyed after a renegade Thorn sold his soul to the devil, or so it was rumoured, but the ruin was still supposed to exist, in some secret hollow beneath the leaves, and Nathan had often looked for it with his friends, though without success. It said in one of the books that an ancient cup or chalice was kept there, some sort of holy relic, but his best friend Hazel said he would never find it, because it could only be found by the pure in heart. (The other boys said he couldn’t have a girl for a best friend, it wasn’t done, but Nathan didn’t understand why, and did what he pleased.)

He wasn’t really looking for the chapel that evening, just walking with his uncle’s dog, the foot-companion he preferred, sniffing along the borders of some undiscovered adventure. There was a dimness among the trees, more shadow than mist, and as they went deeper into the valley the branches grew gnarly and twined together into nets, or reached out to snag fur and clothes. Nathan had to pick his way, but he rarely stumbled and never fell, and the dog, for all his casual gait, was swift and sure-pawed. Concentrating on the ground, they did not see the cloud-edge passing until it slid over them, and the sun struck, slanting through the leafless boughs, filling their vision with a golden haze. For several moments Nathan strode on, half-dazzled, uncertain where he was going. And then the woodland floor gave beneath him, and he was falling in a shower of earth-crumbs and twig-crumbs, bark-scratchings and leaf-crackle, falling down into the dark.

He fell perhaps ten feet, landing on more tree-debris which softened the impact. He seemed to be in a hollow space, like a cave, but the quick changes from dusk to dazzle, from dazzle to semi-dark, proved too much for his brain and his sight took a while to adjust. He glanced upwards, and saw a ragged hole filled with sunlit wood, and a dog-shaped head peering down. He tried to say: I’m all right , but the fall had winded him and his voice emerged as a croak. His arms and legs felt bruised but not broken; his jolted insides gradually settled back into place and a brief queasiness passed. There was a scrabbling noise from above, followed by a slither as Hoover came down to join him. Nathan’s eyes had adjusted by now and he could see they were in a rectangular chamber some twenty feet long, too regular in outline for a cave. Above them the ceiling consisted of a tangle of roots sustaining loose earth, but beyond he made out stubby pillars curving upwards, into arches, and a glimpse of man-made walls on either side, with pointed window-holes choked with leaf-compost and snarled tubers.

Nathan reached in his pocket for the small torch which had been part of his Christmas stocking. The beam was weak and the gloom was not deep enough to enhance it, but it cast an oblong of vague pallor which travelled over the squat columns and the chinks of wall. The stone looked dry and crumbly, like stale bread. He stood up, rather stiffly, and followed the torch-beam into the dimness, Hoover at his side. The soil underfoot thinned, revealing flagstones, some cracked, some thrust upwards by burrowing growths. The beam picked out fragments of carved lettering on the floor and a strange little face peeping out from an architrave, its features blunted with erosion, leaving only the bulge of pitted cheeks under wicked eye-slits, and the jut of broken horns. ‘This is it,’ Nathan whispered. There was no need for him to whisper, but in that place it was instinctive. ‘This is the lost chapel of the Thorns. That face doesn’t look very Christian, does it?’

Читать дальше