“Like a kind of ticket to the right destination.”

They had walked on, frowning, thinking.

Little Bull was no longer with them. He, Twin Stars and their baby son, Tall Bear, as well as Matron and Fickits, had all been sent back through the cupboard as soon as they’d had a talk, right after meeting Omri’s father. They’d all been anxious to return to their own time, especially Matron – a superior sort of nurse, who had been in the middle of her rounds at St Thomas’s Hospital in the London of 1941. The bombing of the city in World War Two had begun, and she was frantically busy. Sergeant Fickits had just been preparing for a drilling session with his trainees in his time, which was back in the nineteen-fifties.

As for the Indians, after a short, tense speech by Little Bull (during which Twin Stars allowed Omri to hold the baby, Tall Bear, in the palm of his hand, a sensation so entrancing that Omri had frankly not listened very carefully) they had asked to be sent back, too, but with the proviso that Omri and his father should make every effort to follow them soon.

“I need counsel ,” Little Bull had said forcefully. “English change toward Iroquois friends. Many years Iroquois fight at side of English against French. Many warriors die. Now they turn from us. Our people do not understand, need chiefs to tell what best to do.” He shook his head, scowling. “Our need is for English man. Wise man, explain what is in English heads,” he said, staring at Omri’s father challengingly.

Next day on the cliff top, Omri’s father said, “I know something about what the Europeans did to the Indians. It’s not a pretty story… I don’t know what we can do to help, but if our damned ancestors are up to some tricks, which they probably are – were – are , the least we can do is find a way to get in there and give the Indians a hand.”

And now here they all were at the supper table, and Omri’s dad was gassing on about going camping. What was he up to?

Everyone was talking. Their mother was on her feet again collecting plates with a great clatter, saying that if there really was a camping holiday in prospect, they’d better do some serious planning, not go at it half-cocked like last time. Gillon was already leafing through the Yellow Pages looking for suppliers of camping equipment, and Adiel was asking if they could go as far as Dartmoor, where they could really feel they were away from civilisation. Their dad was giving every impression of being absolutely serious about the whole project. Only Omri hadn’t joined in.

“When could we do it?” said Adiel, who seemed quite fired up now.

“Oh, I thought in the half-term holiday,” said their father.

“Great! Let’s go for it!”

“There’s a firm here says they do luxury tents,” said Gillon. “No point spending money on some ratty old tent that’ll drop to pieces or let the rain in.”

“No point spending money on some palatial tent that you’ll only use once, if that,” said their mother. “I’ll believe all you laid-back city types are going camping when I actually see it.”

“Well, you won’t see it, Mum,” said Adiel reasonably. “You’re not coming, are you.”

Their mother stopped in the doorway with a pile of dirty plates and there was a moment’s silence. Then she turned and regarded them all with narrowed eyes.

“Well now. Maybe you’d better not count on that. I happen to be the only one in this entire family who has actually had some camping experience. Oh yes!” she added as they all gawked at her, “I was quite the little happy camper when I was in the Girl Guides.”

“Mum! You weren’t a Girl Guide ! You couldn’t have been!” they all – even Omri – yelled.

She drew herself up. “And why not? As a matter of fact I was a platoon leader. I had more badges than anyone else.”

“How many?”

“Eleven and a half. So there.” She turned, walked out, head in air.

“What was the half-badge for?” their dad called after her.

“Making a fire without matches,” she called back. “Only it went out.”

They were all silent for a moment. Then Gillon went back to the Yellow Pages. “ Five -man tents, five -man tents,” he muttered.

“I wish I were a cartoonist,” said their father. “I would love to draw your mother smothered with badges, lighting a fire without matches.” He winked at Omri. It was one of his slow winks, a wink that said, You and I know what this is all about . But Omri didn’t. All he knew was that he couldn’t wait to get his dad alone and find out.

“Of course we’re not really going camping, Dad?”

Omri had managed to get his dad to himself by following him out to his studio across the lane. His father was putting the finishing touches to a large painting of a rooster. He was very into roosters since they moved to the country, but they got weirder and weirder. This latest one looked more like an armful of coloured rags that’d been flung into the air. But Omri liked it somehow. It was like the essence of rooster – all flurry and maleness – rather than the boring, noisy old bird itself.

“Well,” said his dad, tilting his head to one side and standing back with his palette. “I hadn’t planned that we should. I didn’t think the boys would go for it the way they did. Never mind your mother! Really, she is full of surprises…” He stepped up to the easel and put a streak of red near the top of the canvas, like a cock’s comb while the cock is in flight. “… so I’ve changed my plan. Here’s what we’ll do. We’ll arrange that Gillon and you and I will go on a preliminary trip, a sort of dummy run, to Dartmoor to pick out a suitable site and so on, while Adiel’s away at school, and then we’ll do it on a weekend when Gillon won’t want to come.”

“Why won’t he?”

“We’ll fix it so he won’t.”

“How?”

“Watch the forecasts. Pick a very wet weekend when there’s something good on the box.”

“And then?”

“And then, my hearty, outdoor lad, you and I will go off together, ignoring the weather, and no one will miss us for two days, and we’ll ‘go back’ and see what the situation is.”

“Ah!” So that was it. A way of getting away from home, just the two of them. “But have you thought about what we’ll use to go back in ?”

“Yes. I’ve thought.”

“Well, what? We can hardly carry some wardrobe or chest or something big enough in the back of the car!”

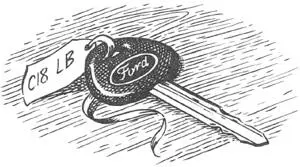

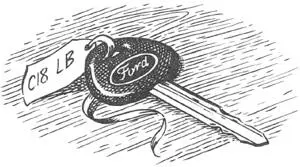

His father put down the palette carefully on his paint-stained table with all its jam jars full of old brushes and its rows of squashed paint tubes. “It came to me today in the square, when I was shopping. I got a load of vegetables and I couldn’t carry them all in one go so the greengrocer said he’d take the other box out for me to the car. He asked me the registration, and I told him, and it burst on me like a blinding light.”

“What, Dad?”

“Go and look at it. The numberplate.”

Omri, frowning, left the studio and crossed the yard to the open bays, in one of which was parked the family car – a third-hand Ford Cortina Estate that his father had recently bought when their old one packed up. His eyes went to the numberplate and he stopped in his tracks.

The next instant he had turned and raced back, bursting into the studio with his face alight.

“Wow, Dad! Wow and treble-wow! You’re brilliant!”

“No, Om. It’s the magic. It couldn’t be coincidence. It means we’re meant to go.”

Читать дальше