The people who have seen this spacesuit are the collections staff of the museum, scientists, researchers and the Apollo astronauts who come to see their suits, often with their grandchildren (Alan Bean, Apollo 12, is the astronaut who visits his suit most often), and NASA engineers. NASA’s design team is working on suits for Mars. The Mars suits will need to last longer and be able to be taken on and off more than the Apollo suits, but they’re a good place to start. Schmitt’s suit is especially useful in aiding with their design, as he tested it to the max, bounding about with rocks in his hand. They’ve looked inside using x-radiography and studied in detail the lunar soil that clings to it.

After marvelling at Schmitt’s suit, I looked around the room. On the bunk adjacent to it I saw a boot sticking out from beneath its sheet. It had a circular patch of Velcro on the sole. ‘What’s that?’ I asked the curators, pointing at the boot. ‘Oh, that’s Neil Armstrong,’ they said. This Velcro-soled boot was covered with an additional lunar boot when it stepped on to the moon but, still, it had covered the foot of Neil Armstrong when he took his ‘one giant step for mankind’.

Only Schmitt and Cernan’s lunar boots are back on Earth: they’re here in the museum collection as two of the most complete flown suits that made it back. The boots Neil wore inside the spaceship had Velcro on the soles so that he could stand still. The interior of the ship had Velcro laid down like a carpet so that, whenever the astronauts needed to be rooted in one place, they could stick themselves on to the ship. Presumably, they walked around making loud, ripping noises.

Neil Armstrong’s suit and under boots have been in storage for five years, having conservation work done on them. They won’t always be behind the scenes and the same goes for a lot of the suits. They’re here resting, between exhibitions, ‘in shavasana position’, as Lisa put it (that’s the yoga position where you lie on your back, meditating). It may be years before these suits are put on display, but it is possible to display them.

Schmitt’s will need to wait decades, at least, until it can come out of storage. Museums have not yet found a way to display it without damage to the suit and its precious moon dust.

Since I saw the suits, they have been on the move. They now live in their new storage facility, in Chantilly, Virginia. The new facility is part of the Air and Space museum’s sister museum, built near the airport, so that new air and space exhibits can be flown straight into the museum collection. The suits were moved in trucks, a few each day, snuggled into crates to keep them safe. The collections staff considered moving them in coffins but decided against it. In their new home, the suits are stored according to mission.

Now that I have seen the suits they wore, how fragile they are, considering they kept men alive on the moon, and now that I have seen lunar soil, on dusty knees 2 centimetres from my nose, the moon landings feel much more immediate. I wasn’t alive when mankind landed on the moon, so I missed the excitement that everyone who was must have felt listening to their radios, watching TV all over Earth and then gazing up at the white thing in the sky and imagining humans there in space. Now I know it wasn’t a hoax (unless of course the sheets we didn’t pull back actually covered Mickey Mouse suits …).

The moon landings also seem more surreal. The suits are made out of fibreglass fabric, a material that was first manufactured for household items. Cathy remembers that her ’parents had fibreglass curtains, the height of fashion in the sixties’. The suits seem far less robust than I had imagined. They have holes where the breathing apparatus was screwed on. They look so normal that they seem strange. They’re very low-tech, very human.

Seeing the suits has made me feel that something greater than NASA and Nixon must have been at work to get those men up there, keep them safe and bring them home. I’ve read that there was only a ten per cent chance the astronauts would make it back alive. Now, when I look at the moon and think of those fragile suits lying in shavasana, it feels to me as if the moon wanted to meet mankind. Maybe Mars will be next.

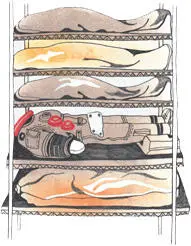

[Spacesuits]The spacesuits are dressed on mannequins and are laid out flat on their backs on metal bunk beds five to six bunks high.

[Planet Earth]‘It suddenly struck me that that tiny pea, pretty and blue, was the Earth. I put up my thumb and shut one eye, and my thumb blotted out the planet Earth. I didn’t feel like a giant. I felt very, very small,’(Neil Armstrong)

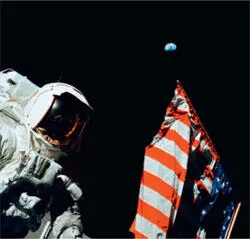

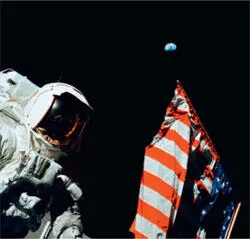

[Schmitt on the moon]Schmitt checks out a lunar boulder on the moon. You can see the lunar rover to the right of the photo.

[Harrison Schmitt’s Spacesuit]Schmitt’s suit is too precious to put on display; it is covered in grey moon dust. I also saw Neil Armstrong’s suit, gloves and boots.

[Apollo 17 moon landing]Schmitt stands by the flag on the moon. You can see Earth in the black sky above.

BROTHER GUY CONSOLMAGNO IS THE curator of the Vatican Observatory. The observatory used to be in Rome, but moved out to the Pope’s summer home, Castel Gandolfo, in Albano, just outside Rome, when light pollution in the city made it impossible to see the stars.

I took a train from Rome to Albano. When I arrived, Brother Guy was waiting on the platform. I had thought he might be in monk’s robes, but he was wearing a red waterproof jacket, jeans and trainers. That is because he is a Jesuit and his order don’t wear robes, they prefer to blend in and work among lay people. He was immediately friendly, bright and charming and I knew it would be a fun day.

We walked up through the sleepy town until we reached the main square. It was quiet but for the sounds of birds and a few people chatting in restaurants. On one side of the square is a pink wall which divides the town from the papal grounds. Built into this wall is a door with a sign beside it carved into stone that reads ‘Specola Vaticana’. We opened the door and entered the Papal Grounds and the observatory’s museum. Guy explained that the Pope’s house is 2 kilometres away from the museum, across orchards and fields.

The observatory isn’t often open to the public. More often than not, the curators and astronomers have the place to themselves. However, the day I visited they were preparing for the arrival of 500 diplomats from around the world the following week and there were several people painting walls and polishing clocks in anticipation.

Читать дальше