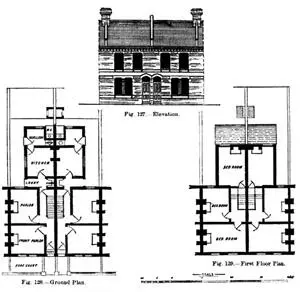

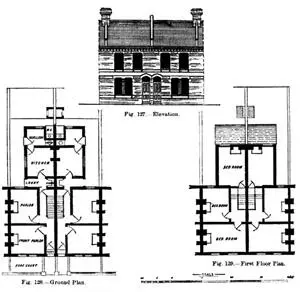

Plans for terraced houses for the lower middle classes, c. 1870s. Note there is no bathroom, and the lavatory is still reached from the outside. The kitchen is spacious, however, with a separate larder (opposite the lobby), and a scullery with a copper. These houses rented for about £30 a year.

In theory, home was the private space of families. In practice – unacknowledged – houses were another aspect of public life. ‘Home’ was created by family life, but the house itself was inextricably linked with worldly success: the size of the house, how it was furnished, where it was located, all were indicative of the family that lived privately within. His family’s mode of private living was yet a further reflection of a man’s public success in the world. Income was no longer derived primarily from land: the professional and merchant classes, as a group, were now substantially wealthier than they had ever been, and they imitated the style of their social superiors in order to live up to their new status: household possessions, types of furnishing, elegance of entertaining and dress, all these ‘home’ aspects were a reflection of success at work. Therefore the public rooms, as an expression of achievement and worldly success, often took up far more of the space in the house than we today consider convenient. Themoney available to spend on household goods was lavished first on those rooms that were on public display. The economist Thorstein Veblen noted the phenomenon in the US, but it holds good for Britain too: ‘Through this discrimination in favour of visible consumption it has come about that the domestic life of most classes is relatively shabby, as compared with the éclat of that overt portion of their life that is carried on before the eyes of observers.’ 14

Semi-detached houses Ealing, built for the prosperous middle classes, with five bedrooms, a dressing room and a bathroom. As well as a larder, there is a storeroom opening off the kitchen. These houses rented for about £50 a year.

Dickens devoted a great deal of attention to the different types of home that were available to his characters. His biographer and friend John Forster remembered, ‘If it is the property of a domestic nature to be personally interested in every detail, the smallest as the greatest of the four walls within which one lives, then no man had it so essentially as Dickens, no man was so inclined naturally to derive his happiness from home concerns.’ 15 The novelist gave no less attention to his characters’ home concerns. There was, first, the ideal, which he elaborated in his ‘Sketches of Young Couples’:

Before marriage and afterwards, let [couples] learn to centre all their hopes of real and lasting happiness in their own fireside; let them cherish the faith that in home … lies the only true source of domestic felicity; let them believe that round the household gods, contentment and tranquillity cluster in their gentlest and most graceful forms; and that many weary hunters of happiness through the noisy world, have learnt this truth too late, and found a cheerful spirit and a quiet mind only at home at last. 16

That even Dickens became entangled in a circular notion that defined itself by referring to itself – that the domestic realm was the place where one found domestic happiness – that even he could not (or found no need to) explain this idea better, is surely telling. Domesticity was so much a part of the spirit of the times that simply to say ‘it is what it is’ was adequate.

Dickens also used the language of domesticity both to create and to mock the role of women at home. In Edwin Drood (1870) Rosa worked at her sewing while her chaperone, Miss Twinkleton, read aloud. Miss Twinkleton did not read ‘fairly’, however:

She … was guilty of … glaring pious frauds. As an instance in point, take the glowing passage: ‘Ever dearest and best adored, said Edward, clasping the dear head to his breast, and drawing the silken hair through his caressing fingers … let us fly from the unsympathetic world and the sterile coldness of the stony-hearted, to the rich warm Paradise of Trust and Love.’ Miss Twinkleton’s fraudulent version tamely ran thus: ‘Ever engaged to me with the consent of our parents on both sides, and the approbation of the silver-haired rector of the district, said Edward, respectfully raising to his lips the taper fingers so skilful in embroidery, tambour, crochet, and other truly feminine arts; let me call on thy papa … and propose a suburban establishment, lowly it may be, but within our means, where he will be always welcome as an evening guest, and where every arrangement shall invest economy and the constant interchange of scholastic acquirements with the attributes of the ministering angel to domestic bliss.’ 17

However comic the intent in the passage above, ‘the ministering angel to domestic bliss’ was what both Dickens and the majority of the population believed women should be. Evangelical ideas had linked the idea of womanliness to women carrying out their biological destiny – to being wives and mothers. That was their job, and to expect to have any other job was a rejection of their God-given place, despite the fact that, by the second half of the century, 25 per cent of women had paying work of necessity, in order to survive. Most of the remaining 75 per cent worked at home. As will be seen, among the middle classes only the very top levels could afford the number of servants that made work for housebound women unnecessary. In spite of this uncomfortable reality, the hierarchy of authority was undisputed: God gave his authority to man, man ruled woman, and woman ruled the household, both children and servants, through the delegated authority she received from man. One of the many books of advice and counsel on how to be better wives and mothers reminded women, ‘The most important person in the household is the head of the family – the father … Though he may, perhaps, spend less time at home than any other member of the family – though he has scarcely a voice in family affairs – though the whole household machinery seems to go on without the assistance of his management – still it does depend entirely on that active brain and those busy hands.’ 18 Sarah Stickney Ellis, an extremely popular writer for women, was even more blunt: ‘It is quite possible you may have more talent [than your husband], with higher attainments, and you may also have been generally more admired; but this has nothing whatever to do with your position as a woman, which is, and must be, inferior to his as a man.’ 19 George Gissing explored this view in his novel The Odd Women (1893). The ominously named Edmund Widdowson ‘regarded [women] as born to perpetual pupilage. Not that their inclinations were necessarily wanton; they were simply incapable of attaining maturity, remained throughout their life imperfect beings, at the mercy of craft, ever liable to be misled by childish misconceptions.’ 20

That this was generally believed, and not simply advice-book cant, can be seen in numerous letters and diaries. Marion Jane Bradley, the wife of a master at Rugby School, wrote in her diary, ‘How important a work is mine. To be a cheerful, loving wife, and forbearing, fond, wise, thoughtful mother, striving ever against self-indulgence and irritability, which often sorely beset me. As a mistress, to be kind, gentle, thoughtful both for the bodies and souls of my servants. As a visitor of the poor to spare myself no trouble so as to relieve wisely and well.’ 21 She saw herself as an entirely reactive character without the husband, children, servants and poor, she had no role. Women were there for encouragement, to help men when they were depressed – in New Grub Street (1891), George Gissing’s novel of literary life on the edge of poverty, the wife and husband quarrel. Amy says, ‘Edwin, let me tell you something. You are getting too fond of speaking in a discouraging way …’ He responds, ‘… granted that … I easily fall into gloomy ways of talk, what is Amy here for?’ 22

Читать дальше