‘It is indeed,’ said my daddy. Then after a pause, during which he scratched his mop of black curls, ‘So that’s what they talk about when they think no one is listening in. Your mama and I will have to discuss that matter.’

‘Don’t tell her you heard it from me.’

‘Your secret is safe,’ said Daddy, giving me a large wink.

The area of Alberta where I grew up and spent almost the first eleven years of my life was known as the Six Towns Area. While the town we lived closest to was known as Fark, Fark wasn’t big enough to be a town, consisting of only a general store and a community hall and hardly big enough to be called a hamlet. We lived on a farm sixty miles more or less west of Edmonton, Alberta, a distance that in the early 1940s might as well have been six thousand miles more or less west of Edmonton, Alberta, because travel was, as they say in polite society, somewhat restricted.

Only three families in the Six Towns Area owned automobiles, and only three families in the Six Towns Area had telephones, a situation that limited not only travel but communication as well.

None of the families who owned automobiles (though actually only two families owned automobiles; the third owned a dump truck), and not one of the families that had a telephone was our family, the O’Days.

One of the families with a telephone was Curly and Gunhilda McClintock, who, in the process of letting their inherited eight-room house with a cistern and indoor plumbing go to rack and ruin, also allowed their telephone service to be cut off, so while they technically had a telephone, the Telephone Company being too lazy or economy-minded to travel the forty miles from Stony Plain to collect it, that telephone was, my daddy said, dead as Billy-be-damned. I never was too sure who Billy-be-damned was.

Because of a lack of travel and a lack of communication, time didn’t mean a whole lot in the Six Towns Area. Daddy claimed he once arrived at Flop Skaalrud’s to find Flop holding a piglet up in the air, the piglet eating crabapples off a tree.

‘Don’t feedin’ him like that take up a lot of time?’ Daddy asked.

Flop Skaalrud looked at him kind of scornfully, Daddy said, and asked, ‘What’s time to a pig?’

When the roads were good, which was for about two weeks in mid-summer if it wasn’t raining and if what we traveled on could seriously be called roads, Daddy and Mama and me traveled to the Fark General Store, presided over by Slow Andy McMahon, all three hundred and some pounds of him, where we bought groceries and the three-week-old Toronto Star Weekly which, my daddy said, even though it was three weeks old served to keep our family relatively in touch with reality, unlike some we knew.

The ‘unlike some we knew’ referred to many of our neighbors who either didn’t know or had totally forgotten that there was a world beyond the Six Towns Area or their town in particular, be it Fark, Doreen Beach, Sangudo, Venusberg, Magnolia, or New Oslo, none of which were big enough to be called towns but were anyway, because town sounded large and hamlet sounded small, and village sounded only somewheres in between.

Events in the Six Towns Area tended to be measured in years or by seasons rather than by exact dates, an example being the summer Truckbox Al McClintock almost got a tryout with the genuine St. Louis Cardinals of the National Baseball League, which old timers still argue about, some insisting it took place the summer of ’45, others willing to bet their life savings that it was the summer of ’46. Events I want to tell you about occurred during what became known outside my family as the summer Jamie O’Day damn near drowned, and inside my family as the summer Jamie damn near drowned, though the summer I damn near drowned was actually a spring, so much so that there were little pieces of ice in the water I damn near drowned in, and it was without question the tail end of a spring thaw that all but did me in.

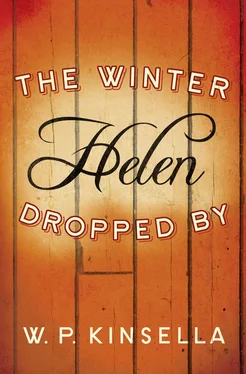

In our family, the summer Jamie damn near drowned was preceded by the winter Helen dropped by, which was preceded by the summer of the reconstituted wedding, preceded by Rosemary’s winter.

It will also be helpful to know about Abigail Uppington, the pig who lived in our kitchen; and about Matilda Torgeson being named in honor of a deceased pig (not Abigail Uppington); and about the infamous Flop Skaalrud’s blatant male aura; as well as Earl J. Rasmussen’s courting of the widow, Mrs. Beatrice Ann Stevenson, the result of that courtship being the reconstituted wedding, the naming of Lousy Louise Kortgaard, and probably twenty or a dozen other events.

I’m just gonna keep my eyes open, watch, and see if all these stories are, like Daddy says, about sex or death, or maybe both at the same time.

It was actually the summer after the winter Helen dropped by that I truly began to measure the events of my life by seasons, in spite of regularly reading the three-week-old editions of the Toronto Star Weekly that were supposed to keep me in touch with reality.

For me, that summer became the summer White Chaps murdered his wife, just as another winter, not the winter Helen dropped by, was remembered for the time when Rosemary, my almost sister, touched my hand.

None of us had ever seen Helen before the winter when she dropped by. ‘None of us’ being the O’Days: me, my father John Martin Duffy O’Day, and my mother Olivia. We lived in a big old house at the end of a trail that was sometimes just a path but was grandly known as Nine Pin Road, a name that didn’t have the least bit to do with bowling. It got named long before Mama and Daddy moved there to hide from the Great Depression, named by a man who, Daddy said, had left the e off of Pine when he wrote to his sister in Norway, so that Nine Pine Road ever after was officially known as Nine Pin Road, even though from our south window you could see a row of nine pines loping across the pasture.

My parents both hailed from South Carolina, though they met in the shadow of Mt. Rushmore, which my daddy says has an array of presidents’ faces carved on it. It is in South Dakota, a considerable distance from South Carolina. Daddy was living in South Dakota, a gandy dancer on the railway, Daddy said he was, though he played baseball on the weekends, and when Mama’s train slipped off the track, coming to rest in the shadow of Mt. Rushmore, Daddy was on the repair crew sent to put the train back on the track. And, as Daddy says, the rest is more or less history.

Daddy got trapped twice, was how come a boy from South Carolina came to be living in Alberta, Canada; three times if you count marriage as a trap, which my daddy didn’t, but which his friends, Earl J. Rasmussen, who lived alone in the hills with about six hundred sheep, and Flop Skaalrud, and Bandy Wicker, the father of my rabbit-snaring buddy Floyd Wicker, and Wasyl Lakusta, who had a good-hearted wife and was one of the Lakustas by the lake, though the lake had been dried up for many a year, did. Earl J. Rasmussen, who was single, had spent the better part of his life courting the widow, Mrs. Beatrice Ann Stevenson, trying to get trapped, and letting her know that he was hers for the trapping.

The widow, Mrs. Beatrice Ann Stevenson, was the poet-in-residence of the Six Towns Area, and could snap off a few lines of Lord Byron or Emily Dickinson or Walt Whitman just in your run-of-the-mill conversation, without being asked to emote or anything of that nature, though Daddy often remarked that it was a shame about Walt Whitman, but that he guessed a few crimes against nature didn’t detract from the fact Walt Whitman was a poet who could touch the heart.

The infamous Flop Skaalrud, as Daddy often remarked, would court anything that twitched. Daddy worded his remarks that way when there were ladies present, but out in the corral he spoke somewhat more directly, as did the women when they were alone in the kitchen of our big old house at the end of Nine Pin Road and didn’t know I was scrunched up in my favorite listening position, squeezed between the cook stove and the wood box.

Читать дальше