‘And who told you that?’

‘Reuben, as a matter of fact.’ And Reuben had reminded him not so very long ago that Alice was coming to the age when women were on a short fuse and had to be handled carefully. Women that age, Reuben warned, blew hot and blew cold at the dropping of a hat, then burst into tears over nothing at all. Queer cattle women were, so think on!

‘He’s entitled to his opinion!’ Alice stirred the stew that thickened lazily on a low gas light then slammed back the lid. Jugged rabbit, stewed rabbit, savoury rabbit and rabbit roasted. Oh for a good thick rib of beef! ‘Well, go and get into your slippers. That’s Daisy’s bus now at the lane end.’

Daisy. Still no letter from the Wrens. Happen they really had forgotten her.

‘Pull up a chair, Daisy love, and have a cup. There’s still a bit of life left in the teapot.’ Polly Purvis set the kettle to boil.

Teapots were kept warm on the hob now, and hot water added to the leaves again and again until the liquid was almost too weak to come out of the spout. And she was luckier than most, Polly reckoned, having fifteen ration books to take to the shops each week. She had solved the egg problem and butter, lard and margarine she could just about manage on, but good red meat and sugar were a constant problem, especially when a land girl did the work of a man to her way of thinking, and needed a bit of packing inside her.

‘You’re all right, Polly? Not working too hard?’

‘I’m fine. The girls are a good crowd. Always popping in for a chat – mostly about boyfriends. I was lucky to get taken on here, Daisy. Keeps me busy enough and keeps my mind off – well, things. And by the way, I had a letter from Keth this morning.’

‘And?’ Daisy raised an eyebrow, not needing to ask the one question that bothered them both.

‘Not one word about that. I asked him outright last time I wrote just what he was doing in Washington, but no straight answer. The job is fine is all I’m told and that he’s saving money. Ought to be grateful for that, at least – our Keth with money in the bank! And he’s obviously managed to get himself a work permit. His letters are cheerful enough and at least he’s safe.’

‘That’s what I keep telling myself, Polly. Sometimes I wouldn’t care if he stayed in America till the war is over. Not very patriotic of me, is it, when Drew’s already in it?’

‘I feel that way, too.’ Polly stirred the tea thoughtfully. ‘But folks hereabouts understand that he’s stranded over there. I don’t feel any shame that he isn’t in the fighting. Wouldn’t want him to suffer like his father did. My Dickon came back from the trenches a bitter man.’

‘Don’t worry.’ Daisy reached for Polly’s hand. ‘One day it will all be over. Just think how marvellous it’ll be! No more blackout, no more air raids and the shops full of things to buy.’

‘And no more killing and wounding and men being blinded.’

‘No more killing,’ Daisy echoed sadly.

‘But you’ll give my best regards to Drew when you see him tonight, won’t you?’ Polly said, rallying. ‘Wish him all the luck in the world from me and Keth?’

‘I think he’ll pop in for a word with you before he goes, but don’t say goodbye to him, will you, Polly? He said sailors are very superstitious about it. You’ve got to say cheerio, or so long, or see you. I think Drew’s going to be all right, though. Jinny Dobb told me he’d come to no harm; said he had a good aura around him. Jin’s a clairvoyant, you know. She can see death in a face – and she isn’t often wrong, either way.’

‘Then I reckon I’d better ask her over for a cup of tea and she can read my cup – tell me when Keth’s going to get himself back home. Mind, I’d settle for knowing just what he’s up to and if he’s getting enough to eat.’

‘And I would give the earth just to speak to him for – oh, twenty seconds; ask him how he is.’

‘Oh, for shame!’ Polly laughed. ‘You could do a lot better’n asking him how he is in twenty seconds! Now then, how about that cup of tea?’ She began to pour, then laughed again. ‘Oh, my goodness! Did I say tea ?’

‘Well, at least it’s hot.’ Daisy joined in the laughter because you had to laugh. If you didn’t, then life would sometimes be simply unbearable.

‘I won’t come over tomorrow night, Drew. I think you should spend it with Aunt Julia and Lady Helen. I’ll be there on Saturday, though, to wave you off.’

The July evening was warm and scented with a mix of honeysuckle and meadowsweet and the uncut hedge was thick with wild white roses. Beneath the trees, on the edge of the wild garden, tiny spotted orchids grew, and lady’s-slipper and purple tufted vetch.

Drew reached for Daisy’s hand, remembering scents and sounds and scenes, storing them in his mind so he might bring them out again some moment when he was in need of them.

‘My ten days have gone very quickly. It seemed like for ever when I got on the train at Plymouth. I think Grandmother is feeling it. Her indigestion is playing her up again, but I’m not to tell Mother, she says. I think she’s had it for quite a while. It’s the war. I think she remembers the last one, and gets a bit afraid. You’ll always pop over to see her, won’t you, Daiz?’

‘Of course I will. I love her a lot, and she was once Mam’s mother-in-law and Mam loves her, too. We’ll see she doesn’t fret too much when you’ve gone back – and there’ll be Mary’s wedding in the afternoon to help take her mind off your going back.’

They skirted the wild garden and crossed the lawn to the linden walk. The leaves on the trees were still fresh with spring greenness and their newly opened flowers threw a sweet, heady perfume over them.

‘Just smell the linden blossom, Daiz. I think I shall take it back with me to barracks – maybe think of it when I’m at sea in a gale, and being sick.’

‘You won’t be sick! Where do you think they’ll send you?’

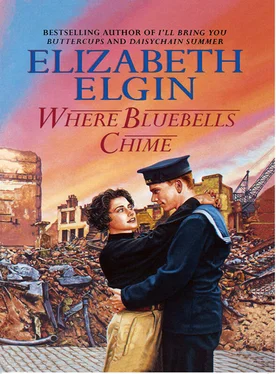

‘Haven’t a clue. They say big ships are more comfortable, but if I had a choice, I think I’d go for something small and more matey – perhaps a frigate. And having said that,’ he grinned, ‘I’ll end up on an aircraft carrier, most likely. Wouldn’t mind Ark Royal. There’s always been an Ark Royal in the British Navy. There was one, even, in Henry Tudor’s time.’

‘Drew! Don’t go for Ark ! Every week, Lord Haw-Haw says the Germans have sunk her!’

‘And every week we know they haven’t. Still, I won’t have a say in the matter. I’m a name and a number for the duration. I do as I’m told. Chiefie in signal school told us to keep our noses clean and our eyes down and we’d be all right. And that’s what I shall do – and count the days to my next leave.’

‘Drew – do you remember how it used to be?’ They had reached the iron railings that separated Rowangarth land from the fields of Home Farm, and stopped to gaze at the shorthorn cows grazing in Fifteen-acre Meadow. ‘It seems no time at all since that last Christmas the Clan was together. Remember? Aunt Julia took a snap of us all. Keth, me, Bas and Kitty and you and Tatty. In the conservatory. We’d all been dancing …’

‘I remember. After that, Uncle Albert started getting a bit huffy about coming over from Kentucky twice a year, but that last summer we were all together was fun, wasn’t it – except for Aunt Clemmy and the fire in Pendenys tower?’

‘And Bas’s hands getting burned. I’m glad Mr Edward had that tower demolished – what was left of it.’

‘Poor Aunt Clemmy. It was an awful way to die. I think, really, it was because she took to brandy after Uncle Elliot was killed. He was her favourite son, Grandmother said. She never got over it. Elliot was her whole life, I believe.’

Читать дальше