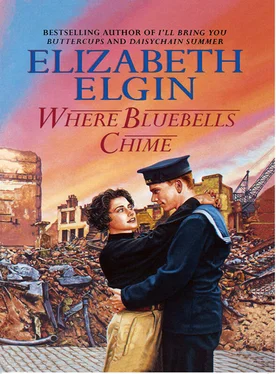

ELIZABETH ELGIN

Where Bluebells Chime

To

my husband George

and to

my daughters Jane and Gillian.

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Family Tree

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

About the Author

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

June 1940

She saw Keth’s letter when the alarm jangled her awake at half-past seven and reached for it, sighing contentment, turning the envelope over to read ‘Open on 20 June’ written across the flap. It must have arrived yesterday, or the day before and Mam had hidden it away then tiptoed into her room last night to prop it against the clock.

She gazed at the colourful American stamp and the air-mail sticker so she might stretch out the seconds before opening it, then frowned to read the postmark. Washington DC instead of Lexington as it almost always was. Why Washington? Quickly, she slit open the envelope.

My darling,

Happy birthday. Close your eyes and know I am thinking of you and wanting you and needing to touch and hold you.

I miss you so much. It should not have been like this. A week ago, I sat my last exam and I know I shall get a good degree. Now I should be packing my cases, heading for New York and a passage home, but nothing is simple any longer. The Atlantic is forbidden, now, to people like me, but I will find a way to be with you.

Since France capitulated I have thought of little else but getting home. Please, darling, take care of yourself and try to keep out of harm’s way. The papers here talk about England being invaded but I can’t believe it can happen – not when I am not there to take care of you and Mum.

There must be a way for us to be together and I will find it. I know you want me to stay in Kentucky, but that is not possible when I need you so desperately and love you so much.

Always remember you are mine.

Keth.

She closed her eyes tightly, trying to smile away the tears that threatened because if she were to weep on her birthday then she would weep all year, Mam said.

‘The summer of ’forty I’ll be back,’ Keth promised, when they parted, but he could not, must not come home.

Today she was twenty and next year, when she came of age, was to have been her wedding day – well, not quite on her birthday, it being a Friday and Friday an unlucky day for weddings. That was why she had ringed round the day after; ringed it on every calendar in the house.

June 21 1941. At All Souls’, Holdenby, by the Reverend Nathan Sutton. Keth Purvis to Daisy Julia Dwerryhouse.

She had read the announcement of their wedding so often in her dreamings. Daisy Purvis. Mrs Keth Purvis. She had promised never to write her married name – not before the wedding that was. As unlucky as a Friday marrying, Mam said, so she had never done it. But it hadn’t stopped her saying it secretly and softly. Daisy Julia Purvis. It made a sound like a love song, like nightingales singing, like the sighing hush of silence before two lovers kiss.

The summer of ’forty. It had been her watchword; words to wear like a talisman, to say over and over when she missed him and wanted him unbearably.

Yet now the summer of ’forty had come and there should have been a letter telling her that soon he’d be sailing from New York, and would she be at Southampton – or Tilbury or Liverpool, perhaps – to meet him when he docked?

Sometimes it had been like that, but sometimes in her dreamings Keth had surprised her, had been waiting where Rowangarth Lane branched off into Brattocks Wood and the footpath that ran through the trees to Keeper’s Cottage; standing there in grey flannel trousers and a white shirt, just as he had been two years ago.

The summer of ’thirty-eight, it had been – their daisychain summer – yet now that longed-for summer of ’forty had arrived and Keth was still in Kentucky. It was where, truth known, she wanted him to stay.

Don’t come home, Keth. Stay in America where you’ll be safe.

America wasn’t at war. America was safety and young men living their lives without fear of call-up; young men knowing they could make plans, go to university, get jobs, stay alive. So she didn’t really want that letter saying he was coming home because if he did, They , the faceless ones, would take him. There had been no heady, patriotic rush to volunteer as there was in Dada’s war. This time, They had already put their mark on every fit young man of twenty-one and dubbed them the militia. Conscripts, really. Six weeks in barracks; forty-odd days in which to accept the discipline of life in the armed forces, to march like automatons in foot-blistering boots; learn to salute Authority and acknowledge that henceforth and for the duration of hostilities, each was no more than a surname and a number. Then away to active service, and some of them killed already.

Stay, Keth. She sent her thoughts winging high and far. I’d rather wait four years, if four years it takes, than have you no more than a name on a gravestone in some foreign cemetery.

She heard the creaking of the stairs and laid her lips briefly to the letter in her hand. Then she swung her feet to the floor. Mam was coming to wish her a happy birthday. Daisy forced her lips into a smile …

When Daisy said goodbye to Reuben Pickering that night, he stood at his almshouse door, waiting to wave to her as she reached the corner. She always turned for one last wave and every time she did she wondered if she would see him again. You never knew what might happen in wartime, and besides, Reuben was frail and old; very old. Over ninety, Mam said, though she would never tell how many years over ninety. You didn’t remind people, especially Uncle Reuben, about their age, she admonished when Daisy once asked. So Daisy always tried, now, to treat the retired gamekeeper as if every time she saw him would be the very last and to be especially kind to him, not just for the sake of her conscience, but because she loved him very much.

Reuben was a part of her life, had always been there – a part of Mam’s life, too. A sort of father, really, because Mam had never had one – or not that she remembered. That was why today in her dinner hour, Daisy had stood in a queue outside a sweet shop and when she reached the counter, had chosen humbugs because they were Reuben’s favourite, though she would have to tell him she was sorry there had been no tobacco queue, but that she would try to get him some tomorrow.

Tobacco and cigarettes were even harder to come by now than humbugs. But yesterday she hadn’t looked for queues during her dinner hour. Yesterday she had –

Daisy blinked her eyes as she stepped from the mellow evening sunlight and into the green-cool dimness of Brattocks Wood, breathing in the damp, mossy scent of it to calm herself, because whenever she thought of what she had done yesterday in her dinner hour, her heart started to bump – especially when she realized that before so very much longer she would have to tell her parents about it. She had almost decided it must be tonight, though it would be awful, telling them on her birthday.

Читать дальше